Cindy Blackstock recalls when a justice department lawyer reached out to her last April to see if she’d consider joining her human rights case with a new pending class action lawsuit against Canada, also involving First Nations children in care, on the matter of providing victims compensation.

Blackstock said she’d agree on the condition the Trudeau government did one thing: Don’t fight certification of the class-action case as a sign of good faith.

That meeting between Blackstock and the general counsel in the civil litigation section, happened April 25, about two months after Xavier Moushoom filed a $3 billion class-action lawsuit March 5 in Federal court after having lived in 14 different foster homes in Quebec.

Blackstock said she never heard from the lawyer again.

“When that [lawyer] came over he had about a half an hour discussion with us and he said he would get back to us and he never did. That class action is still making its way through the process. Canada still hasn’t consented to certify it,” Blackstock told APTN News.

Had Trudeau agreed, Blackstock said he likely wouldn’t be in the situation he finds himself today, in another fight against the First Nations woman where he hasn’t won a single round since the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal first made its historic ruling on Jan. 26, 2016 ordering Canada to cease purposely underfunding on-reserve child welfare. The tribunal has had to make seven non-compliance orders since to force Canada to act.

That includes orders to properly fund Jordan’s Principle, a program that provides medical care funding for on-reserve children and an order to increase financial support for prevention-based services for on-reserve child welfare.

In each of the those cases, Canada has responded to a degree, but not without the tribunal issuing non-compliance orders.

It’s latest order, the tribunal said on Sept. 6 that every past, current and future First Nations child, or guardian, is entitled to $40,000 from Canada for being removed from their families and put in the child welfare system, with the exception of guardians who “were found responsible for sexual abuse, physical abuse or psychological abuse.”

The order continues to apply until the tribunal believes Canada has stopped its “willful and reckless” discriminatory underfunding of First Nations child welfare since its ruling. The longer Canada waits to act and fund child welfare properly the more the number increases as First Nations children continue to be removed from their homes at a higher rate across the country. Furthermore, there are still several orders outstanding, which are explained below.

Now Blackstock believes Trudeau is trying to cut her out of the picture by seeking to have the Federal court dismiss the tribunal’s compensation order.

“That’s been the pattern in this,” she said. “They retaliated against me in the past and everything else. I don’t think they like dealing with me because I hold them accountable.

“I don’t think they get yet what they have done to these kids. They are still very much in denial.”

Former prime minister Stephen Harper deployed similar tactics, and failed, to get rid of Blackstock in Federal court after she first filed her complaint at the human rights tribunal in 2007 through her organization, the First Nation Child and Family Caring Society, as long with the Assembly of First Nations.

The tribunal, and Canada’s privacy commissioner also found the Harper government guilty of employing bureaucrats to spy on her.

NDP MP Charlie Angus also believes appealing to the Federal court is a clear attempt by Trudeau to get rid of Blackstock.

“The government is going out of their way to try and marginalize Cindy Blackstock,” said Angus. “I think they are trying to shut down the tribunal… They are going make a big mistake and it’s going to blow up in their face.”

Court records filed by Canada suggest if it were to comply with the order as it stands Canada would have to pay out at least $5 billion by next year, with the number rising to approximately $8 billion by 2026 because of the rising number of apprehensions.

Instead, the Trudeau government is trying to shepherd in a settlement package like it negotiated with ’60s Scoop and residential Day School survivors during its first term. They mirror the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement that provided survivors with common experience payments and, depending on the severity of the abuse suffered, survivors could qualify for more money.

This means dealing directly with survivors and cutting out organizations says Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett according to a recorded conversation filed in Federal court last Friday by Blackstock as part of her affidavit opposing Canada’s request to have the compensation order dismissed.

The recording, in many ways, outlines Trudeau’s working theory on how it intends to try to eliminate Blackstock.

Bennett was questioned by Nipissing First Nation Chief Scott McLeod on Oct. 11 about the Liberal government’s efforts to quash the tribunal’s order.

A letter from McLeod to Blackstock dated Oct. 15, 2019 says the meeting also included Liberal federal election candidate for Parry Sound-Muskoka Trisha Cowie, who is a lawyer from Hiawatha First Nation, and other chiefs from the area.

McLeod didn’t have writing materials so he says he recorded the conversation, which Bennett was unaware.

Early on in the conversation, McLeod asks Bennett why she isn’t working with Blackstock’s organization and the AFN to meet the tribunal’s Dec. 10 deadline to come up with a plan to how children would get the $40,000.

“I think that the concern has been we, our responsibility is to all of the survivors. I, we are not, I think, comfortable letting them design a plan without the survivors and the people harmed at the table. This isn’t about a, organizations, this is actually about people,” Bennett says according to the transcript.

Bennett goes on to say she can’t accept a plan from Blackstock and that the tribunal is out of its depth with the compensation order.

“We do not believe that we could accept a plan unless, unless the people harmed actually are, are behind that plan, and agree that it’s fair. If, if something is assigned, and people don’t think it’s fair, they will be retraumatized for the rest of their life,” Bennett says. “This is not the way these things are, are done. This is not really the way the CHRT, the CHRT was really set up for individual cases and that’s why the $40,000 is the max they can give. This process was for individual cases. This is something that is a very large class of people who were harmed, but it’s only part of the people.”

She’s referring to the fact the tribunal order goes back to 2007, while there are more victims dating back to 1991, which is the cut off date for the ’60s Scoop survivors.

“What happens to all those people in between?” Bennett says, referring to the victims between 1991 to 2007.

While Blackstock was open to discussing joining human rights case with class-action she told APTN they are two different matters.

“The Canadian Human Rights Act doesn’t stop anybody from getting additional funds through the class-action if that is the way it worked out. It almost seems like Bennett wants to reduce the amount,” said Blackstock.

Indigenous Services Minister Seamus O’Regan said the Trudeau government isn’t trying to cut out Blackstock’s organization.

“As we’ve said before, we agree with the need for compensation. We are not seeking to remove the Caring Society from this process,” O’Regan said, in an emailed statement. “We will continue to work with the AFN, the Caring Society, and other partners to find the best way forward so that we can bring healing and recognition of the harms suffered by First Nations children in care.”

Blackstock also said the public has also been getting mixed messages from Trudeau and what’s filed in court.

Bennett suggests, according to the transcript, that Trudeau’s statements on the tribunal’s compensation order are “way more important” than the government’s official legal position.

“I am telling you, that whatever the Prime Minister says, and what the Prime Minister has demonstrated to do, is way more important than anything what any lawyer from the Department of Justice has to say there,” she says to McLeod.

“I think that there are certain things that lawyers say in courting the pleading that are really obnoxious. And I’m the first one to say that as the client I hate that … but people need to know that this is not what we or the Prime Minister feel.”

McLeod agreed this was sending mixed messages to First Nations.

“I am no legal expert but it’s almost as if you’re saying don’t pay attention to the devils in the detail, listen to what we’re saying,” McLeod responds later in the 70-minute conversation.

“Do you think that paying a toddler, or somebody who was there, in care for a week, the same as somebody who was in 10 different families, abuse in every one,” Bennett says to McLeod. “We want to get to the table and get it right. That’s, that’s all we wanna do. We want to be able to get it right.”

The tribunal’s ruling provides every single First Nations child the same amount of $40,000 regardless of how long they were in care.

But court filings suggest the Trudeau government has not wanted to get to the table, at least not with Blackstock or the AFN. It has known for nearly four years the children were entitled to compensation, yet have done nothing to address it said Angus.

Angus said the bait and switch approach is out of line.

“It shows a willful and reckless disregard for the crisis of Indigenous children in this country. They have refused to negotiate, refused to deal with this issue,” he said. “For Justin Trudeau to lie, publicly, and say they accept compensation and they want to talk and they want to work this out is continuation of willful and reckless discrimination. Carolyn Bennett has zero credibility on this file.

“She can not be at this table in a ministerial capacity because she has poisoned the well.”

Blackstock is also adamantly against the federal government speaking directly to survivors and said this in her letter to Trudeau.

“This is morally inappropriate given Canada’s role in the discrimination that led to the compensation being ordered, ” Blackstock wrote. “We would request that Canada constrain its conversations on compensation to discussions with the parties to the litigation, using the proper process.

Meanwhile, Canada’s position hasn’t changed. It is trying to squash the tribunal’s order on compensation and hearings are scheduled for Nov. 25-26.

And as for the other orders still outstanding, and keeping Canada from complying with the tribunal, includes capital funding for First Nation child welfare agencies across the country. The tribunal found Canada underfunded these agencies in its ruling, however by Feb. 1, 2018, two years later, Canada still hadn’t increased funding to the agencies resulting in a non-compliance hearing. The tribunal ruled Canada increase the funding retroactive to its Jan. 26, 2016 ruling.

On Feb. 21, 2018 the first retroactive payment went out to First Nation agencies. As of this past summer, nearly $300 million had rolled out, or has been earmarked, for what’s called prevention services and almost half has gone to Ontario.

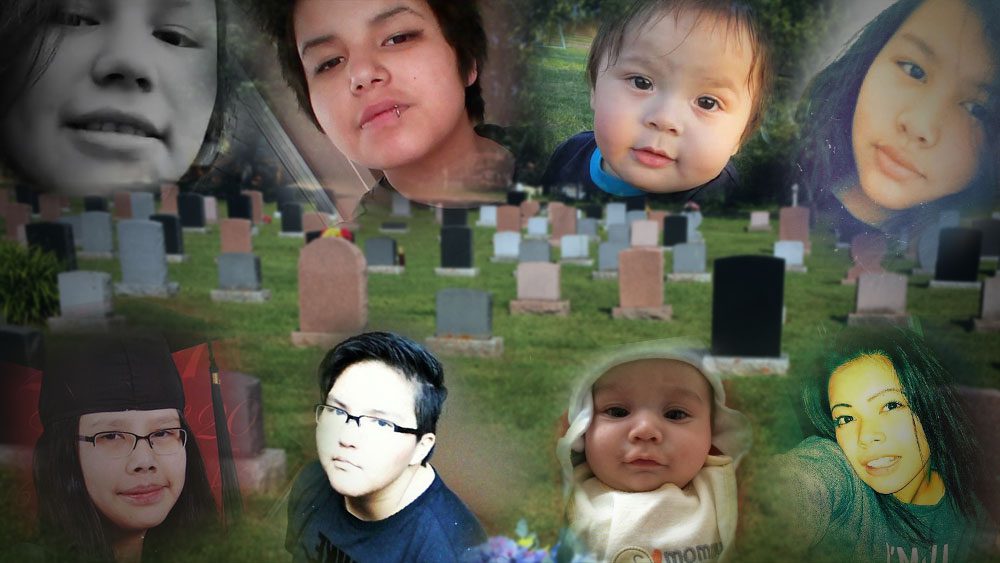

As well, in the two years it took Trudeau to pay this money 48 Indigenous children connected to the First Nation child welfare agencies in Ontario died as reported by APTN Sept. 25.

Most of these deaths were suicides, including Kanina Sue Turtle, 15, on Oct. 29, 2016.

Jolynn Winter 12, who died by suicide Jan. 8, 2017. She had been in care all her. Two days later her cousin also died by suicide, but wasn’t in care. The tribunal found the federal government policy played a part in these girls deaths after their community of Wapekeka requested specialized funding for suicide prevention months earlier but were declined by Health Canada because it was a bad time for the department’s budget.

Amy Owen, 13, died by suicide in an Ottawa group home on April 16, 2017.

There were also other deaths, including Tammy Keeash, 17, who was supposed to be in 24-hour supervision only to be found lifeless in a Thunder Bay waterway after a night of drinking. Her death was ruled accidental.

APTN’s investigation found 102 Indigenous children died between 2013 and 2017 connected to the child welfare system, including 72 in northern Ontario. During those five years three First Nation agencies covering much of the region were underfunded approximately $400 million compared to agencies in southern Ontario.

“We know the families. I’ve met families who have lost children in this and who have other children in the system. The children are literally disappeared into a gulag of hopelessness,” said Angus, adding this is happening across the country.

The tribunal has also ordered Canada to provide Jordan’s Principle funds for non-status children living off-reserve.

Obviously delaying and delaying is very bad for First Nations people because more of them die and Trudeau is using the same tactic than Harper to delay so the government will have to pay less to the victimes!!!!

I agree that the government is saying here: “Do not pay attention to what we are actually doing just to what we say.” Not a good way to deal with this long standing problem, and a response I find very disappointing, from a government I voted for because it make promises to our Indigenous peoples.

What Canada says and what Canada does are two different things, and with purpose; like donald trump the government of Canada (liberal and conservative) gives soundbites to their white voters telling them the govt. is paying and paying Indigenous People, but the truth is they stall, and refuse. And children suffer. So when Indigenous Peoples finally stand up and complain about horrific treatment and injustice, white voters are made to feel angry that they are giving so much…but nothing has been given. It is an old game played for decades against Indigenous Peoples. Shame on us all.