“Every three days. Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday,

a child connected to care dies…”

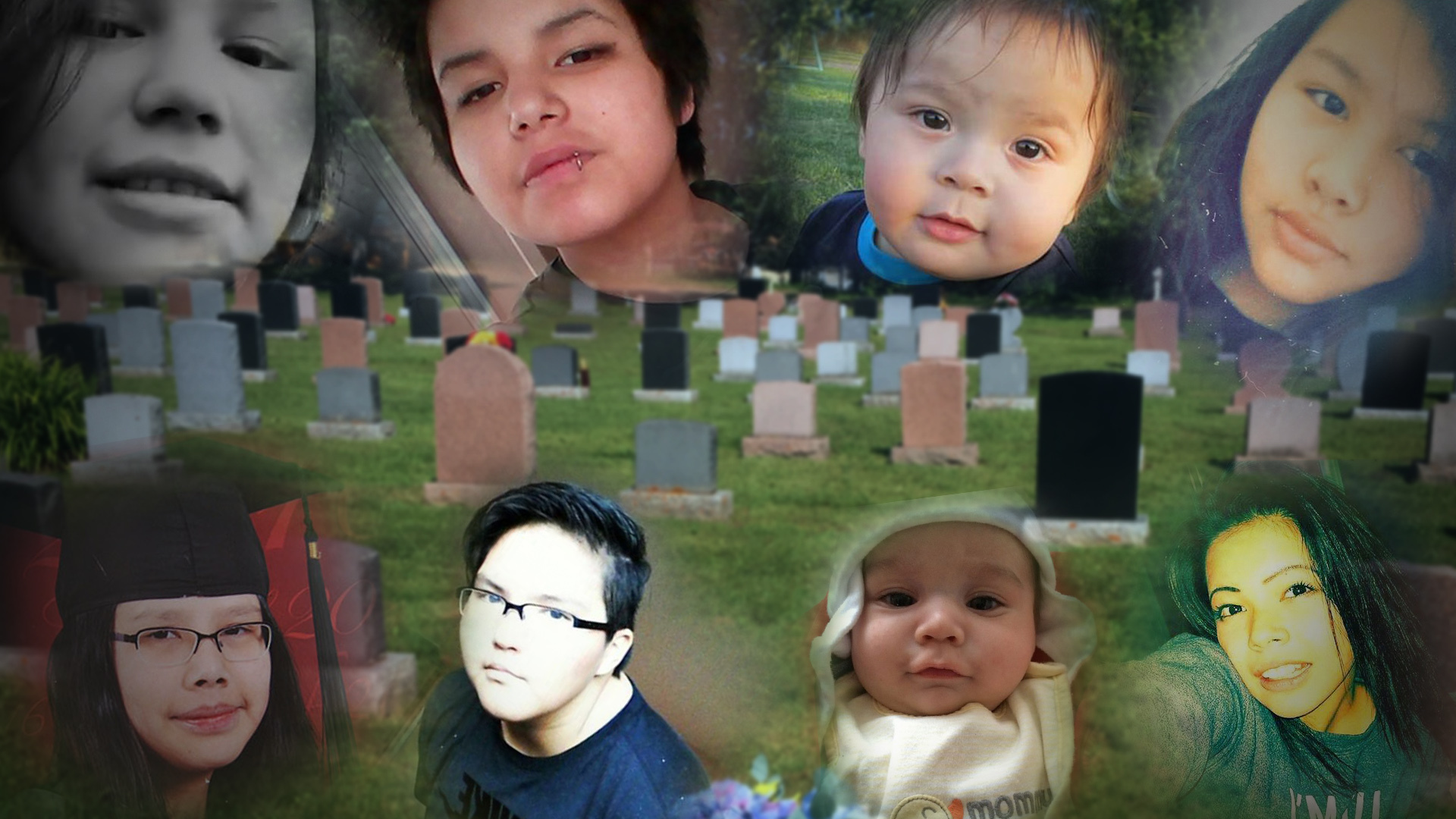

Seventy-two Indigenous children connected to child welfare died in northern Ontario, where three Indigenous agencies covering most of the territory were underfunded approximately $400 million over a five-year period.

The number of deaths jumps to 102 Indigenous children when looking at the entire province between 2013 to 2017.

And almost half of the deaths, 48 involving Indigenous agencies, happened in the two years it took Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to respond to multiple orders made by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal that first found Canada guilty of purposely underfunding on-reserve child welfare in its historic decision on Jan. 26, 2016.

“Nothing the government can do can make up for the wrongs it consciously perpetrated against kids. And I want to emphasize that it was conscious. It wasn’t an accident,” said Cindy Blackstock who led the fight against Canada, along with the Assembly of First Nations, to bring Canada to task over discriminating against First Nations children through the tribunal.

But while the federal government may be the bagman, funding at least 93 per cent of on-reserve child welfare, the Ontario government created the system where these children died and provides the law within which the child welfare agencies operate. It’s a system that has been found to be a complete failure over and over up until just last year when the chief coroner of Ontario released a special report into the deaths of 12 children who died in care, eight of whom were Indigenous.

As well, the 102 deaths marks the lowest number on record as APTN’s investigation reveals data was never collected properly over this five-year period.

Many believe it to be much higher.

In fact, while it’s improving, Ontario’s data collection still faces some serious questions, such as how many Indigenous kids are in care today in Ontario?

No one knows the total number.

APTN reporter Kenneth Jackson has spent over two years unraveling Ontario’s child welfare system beginning with the death of Amy Owen, a 13 year old girl who died by suicide in an Ottawa group home over 2,000 kilometres from her First Nation in northwestern Ontario.

The work was made more difficult because the system – from the agencies to the Ontario government to even the courts – keep information from the public and, as APTN encountered, can mislead it at times.

Caught in the middle of all this are the parents left without their children.

This is: Death as Expected.

(These are just a few of the Indigenous children that died connected to Ontario’s child welfare system between 2013-2017. Photo illustration: Alicia Don.)

Every year the office of the chief coroner in Ontario publishes a document based on the number of paediatric deaths, from newborns to 19 years old, called the Paediatric Death Review Committee report and posts it online. There’s never a press release alerting the public, or media, to the report based on approximately 1,100 paediatric deaths on average each year. It is shared with policy makers.

Its purpose is predominately to look for trends in the data to hopefully prevent deaths in the future and a portion of the report focuses on deaths involving the child welfare system.

It’s in these reports that APTN first learned of the 102 deaths, but it wasn’t that simple.

Earlier this year, APTN asked the coroner’s office if it had the number of Indigenous children that died in care over the last five years. The coroner’s office later emailed a chart showing that 19 Indigenous kids died over that period.

APTN knew the number was low having written about so many of these deaths and having knowledge of several more that went unreported.

But the devil is in the details and in this case that meant the footnote on the chart where it said the number was based on how the province defines “in care”. That’s foster care, group homes, jails and hospitals. But there are many other ways child welfare agencies in Ontario can be directly involved in a child’s life.

APTN was then alerted to the most recent paediatric death report for 2017. There was a much larger number: 32 deaths “involving” child welfare.

“Involving” is the key word.

The coroner tracks deaths of children who, or whose family, personally had contact with an agency within 12 months of their death. On average, about 70 per cent of the children had an open agency file at the time of their death.

APTN then examined reports going back to 2013 adding up the deaths. The coroner mentions in the reports that the data is limited based on the way the Ontario government collected it.

Still, it was the starting point.

But why were these children dying?

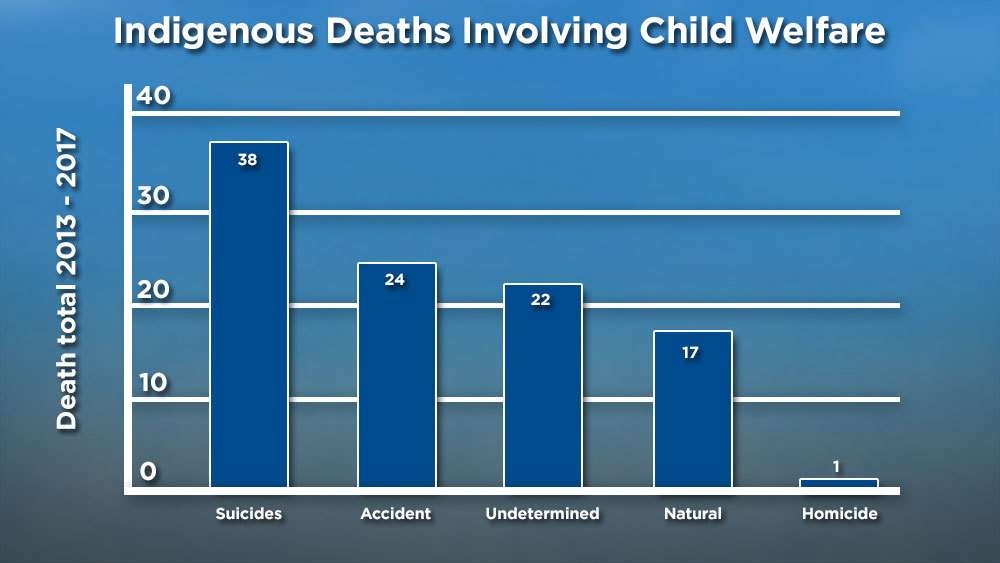

(This is the official number of Indigenous children connected to Ontario’s child welfare system that died between 2013-2017. Chart: Alicia Don.)

There are 50 child welfare agencies in Ontario, including 11 that are called Indigenous well-being societies (a new Indigenous agency opened last February but is not part of this story). Each submits quarterly reports to the ministry of children, community and social services (formally ministry of children and youth services). The reports are supposed to track every type of care agencies use for children and the funding agencies were allocated.

APTN requested these reports through the Freedom of Information Act covering the span of the 102 deaths and ended up settling on what’s known as a roll-up, where this data is put in spreadsheets and added up annually. It was a massive amount of data and not easily readable as some portions were just scanned print-outs of the spreadsheets which meant each had to be individually put in a spreadsheet.

Other parts had the names of agencies cut off for an entire year and we had to compare previous years to match numbers to agencies based on the order they were in.

“All this data was presented to you in a way that was so difficult to assess,” said Dr. Kim Snow, a professor at Ryerson University and leading expert in child welfare who is typically called upon to investigate systemic issues across the province.

That includes reports for the former Ontario child advocate who had Snow examine what’s known as serious occurrence reports that are submitted to the province every time a child in care is hurt, goes missing or dies. Snow was also enlisted by the chief coroner to be part of what’s known as a special panel that released a report in September 2018 into the 12 deaths of children in care between 2014 and 2017.

The panel examined each child’s file, some over 1,000 pages, and got a look into how agencies operate. Snow, and the other experts, found the system was lacking in almost every area from trained staff, services and foster care. The term “lack of” is mentioned 37 times in the 86-page report.

Snow agreed to help APTN analyze the data along with the help of her grad student, Marina Apostolopoulos, and spent the summer going over every number.

Having previously examined the files of northern agencies during the panel review, Snow already knew they were struggling and noticed quickly that funding was drastically lower for Indigenous agencies in northern Ontario. She developed a formula to compare funding to non-Indigenous agencies in southern Ontario with similar caseload, like average children in care annually.

Snow knew these three Indigenous agencies were underfunded by approximately $400 million between 2013 to 2017: Tikinagan Child and Family Services that serves over 30 First Nations in northwestern Ontario, Dilico Anishinabek Family Care serving 13 nations around Thunder Bay and Payukotayno: James and Hudson Bay Family Services, which includes Attawapiskat.

The three agencies cover most of northern Ontario and APTN can also confirm deaths with each. The number rises to $500 million if you go back just one more year to 2012.

“You have less funding, you have less qualified staff, you have a more crisis-like response and you often have to fly people from one place to another to find a place of safety,” said Snow, explaining how much more difficult it is for these agencies compared to, say, Windsor-Essex Children’s Aid Society.

Windsor had an average of 613 children in care in 2013 and was allocated $56 million, while Dilico had an average of 583 kids in care and was allocated $26 million. It only gets worse.

Even as Windsor’s children in care went down its funding increased. Dilico’s kids in care would stay the same and saw barely an increase over the next fours years. In total, Dilico was underfunded approximately $137 million in comparison in five years.

“The end result is kids die. Kids are always at the epicentre of structural inequality,” said Snow.

But families don’t see the funding issues when agency workers show up to remove their children, mostly due to poverty-related issues. Snow said the number of children being abused physically or sexually is low.

The families APTN interviewed see the agencies as the enemy.

That includes the family of Kanina Sue Turtle who died Oct. 29, 2016. She was 15.

There are suing the agency for $5.9 million, alleging Tikinagan is at fault for Turtle dying by suicide in one of their short-term stay homes – known as an agency-operated home – in Sioux Lookout.

(Kanina Sue Turtle’s brother Winter Suggashie, left, and her mother Barbara Suggashie walk for suicide awareness in the summer of 2018. They were also walking to the foster home where Turtle died by suicide. Barbara would go in the room for the first time. Photo: Kenneth Jackson/APTN)

Turtle filmed her death which was first reviewed, and reported, by APTN in late February 2018. It shows she was left alone for more than 46 minutes despite being chronically suicidal. APTN went on to report she missed every scheduled appointment with a crisis counsellor in the five days before her death and that Tikinagan suspected she was part of a suicide pact. Tikinagan also kept her three suicide letters from her family for over two years.

Tikinagan denies in court documents that the agency is to blame for the death, but has filed a cross-action in the claim suing the Sioux Lookout hospital and doctors saying if anyone is at fault it’s them.

Shortly after Turtle died her girlfriend, Jolynn Winter, 12, also died by suicide while at home in Wapekeka First Nation. After Turtle’s death she tried to kill herself and was sent to Wapekeka for what is believed to be the first time in her life. APTN previously reported her grandmother didn’t know Winter was her granddaughter until Tikinagan returned her home a couple months before her death Jan. 8, 2017.

Then Amy Owen died by suicide in Ottawa. Both she and Kanina were from Poplar Hill First Nation.

Owen’s family is also suing Tikinagan and the private group home operator, Mary Homes. Both deny all allegations and have also blamed each other in court filings. Owen, like Turtle, was left alone while chronically suicidal. The coroner said she was alone for an hour, while Mary Homes alleges 10 minutes, according to allegations based on the contents of documents filed in court that have not yet been proven in court.

Soon after Owen’s death another child in Tikinagan’s care died. Tammy Keeash, 17, was found in a Thunder Bay waterway on May 6, 2017, which was later ruled to be an accidental drowning. It enraged her mother, Pearl Slipperjack, who was angry at Tikinagan, as well as her family who gave her copious amounts of alcohol the night of her death and then left her passed out on a hill in Chapples park. Tammy was supposed to be under 24-hour watch by the foster home where she was placed.

Slipperjack passed away the following summer from natural causes, but before her death she told APTN she had a lawyer and was going to sue Tikinagan.

Shortly after Slipperjack’s death, and before the special panel report was released in September 2018 that included Tammy’s death, APTN got an anonymous tip in Ottawa about a civil action between Tikinagan and Dilico involving Tammy’s death and “others” filed at the Thunder Bay courthouse.

APTN pulled hundreds of pages from the case that outlined a turf war between the agencies dating back to the summer of 2016.

Dilico filed an emergency injunction to stop Tikinagan from placing children in Thunder Bay foster homes, arguing it was Dilico’s jurisdiction and any Indigenous kid in care in the city was under its oversight. Tikinagan disagreed and battle lines were drawn eventually turning into mediation with Sen. Murray Sinclair overseeing it.

It remained at a standstill for about a year until Tammy died. Days after her death Dilico filed another emergency injunction.

This time Dilico named Tammy as a reason why Tikinagan shouldn’t be able to place kids in Thunder Bay and keep authority over them.

This resulted in a fury of filings and more documentary evidence submitted, which APTN obtained.

APTN later published this story: Foster homes investigated 7 times within a year but Ontario didn’t close them until Tammy Keeash died: court documents

(A cross still marks the spot where the body of Tammy Keeash, 17, was found in Thunder Bay. Photo: Kenneth Jackson/APTN)

APTN traveled to Thunder Bay to check for anything new in the civil filing in late February 2019.

APTN gave the civil counter clerk the court file number. A few minutes later she wheeled over a large cart about a metre and a half tall stacked with large folders.

Within five minutes another court worker appeared and asked for the documents back.

“It’s a child welfare case,” she snapped with just a glance at the files. “I don’t think you can see these.”

She said she wasn’t “comfortable” with APTN having the documents.

(Tikinagan had failed to have the documents sealed a year prior. Portions of the documents were supposed to be redacted so no child could be identified.)

This happened in a matter of a few minutes.

APTN pushed to speak to a manager and soon Laurie Kopanski appeared, a middle-aged Caucasian woman with dark, dirty blond hair.

She repeated she wasn’t sure she could allow APTN to view the files through thick security glass at the counter because she had a “concern.” When APTN asked what it was she wouldn’t say.

It was around this time that APTN went to Twitter to report what was happening.

At this very moment staff at the Thunder Bay courthouse is refusing to let me see documents in a civil lawsuit involving children’s aid societies. It’s not sealed.

— Kenneth Jackson (@afixedaddress) February 26, 2019

“I need to speak to the judge,” said Kopanski, adding it may take a couple days.

That wasn’t good enough. It needed to happen immediately.

The judge on the case, Justice Bonnie Warkentin, told Kopanski there was no sealing order but she needed to ensure the files had been redacted by calling Tikinagan, the defendant in the case. Later that day APTN returned to the courthouse to speak with Kopanski again.

APTN informed her it had previously viewed the file and paid money for copies.

“I had a concern over what was publicly accessible,” she said.

APTN hired a lawyer to push for access. A letter from the attorney general’s office to APTN claimed staff had noticed redactions hadn’t been made.

“Despite the files having been previously viewed in 2018, court staff noticed that the redactions that had been made did not appear to effectively redact information … Ms. Kopanski sought Justice Warkentin’s direction…” said Vaia Pappas, a director of court services in a March 13, 2019 letter.

While it was later confirmed some redactions were done poorly, it took lawyers from Tikinagan and Dilico several trips to the courthouse to confirm, it simply couldn’t have been done in the handful of minutes court staff were claiming in the letter.

Letters continued to go back and forth between lawyers until finally APTN was given access in late April earlier this year.

APTN flew back up to Thunder Bay to view the files but this time asked to see all lawsuits involving Tikinagan and Dilico going back five years. Tikinagan had a couple unremarkable dismissed cases, but not Dilico.

Up until this point APTN had only heard stories about Dilico.

Documents in the courthouse confirmed deaths of infants, another case where a child was placed in the home of a registered sex offender and allegations of an agency in apparent disarray around the same time in 2014.

Soon the death total rose to four cases involving dead infants within seven months involving Dilico.

Once APTN published stories about Dilico and the deaths of infants more and more people started contacting APTN with their own stories. It wasn’t necessarily always about deaths but about the fear running through the communities.

One mother told APTN it took months for Dilico to respond to her lawyer because she was revoking her consent to have her children in care.

She had a child in care under a customary care agreement that was supposed to be more culturally appropriate and involve the child’s First Nation as support.

Dilico made a shift to this type of care just before 2014, according to former employees and confirmed by the data Dr. Kim Snow analyzed.

In fact, Dilico went from 19,771 days of customary care in the 2012/13 fiscal year to 78,142 days the following year.

It’s only gone up from there.

(Dilico Anishinabek Family Care’s headquarters is located on Fort William First Nation next to Thunder Bay, Ont. Photo: Jason Leroux/APTN)

However, Marco Frangione, a lawyer who represents families in child welfare cases in northwestern Ontario, said these agreements are often signed under duress and without a lawyer across all agencies.

“In the overwhelming majority of cases these agreements are drafted without the benefit of legal council,” said Frangione. “They are told if they do retain a lawyer there could be consequences and I have seen this time and time again.”

And once the agreements are signed, in his experience, they are almost never renewed with the parents’ participation. That’s what happened with Jolynn Winter according to her grandmother who told APTN last year that while she was councillor at Wapekeka she remembered signing customary care agreements every six months for someone named Jolynn, extending her care, only she didn’t know it was her granddaughter at the time.

“I can state seeing children not having access to their parents or seeing their parents infrequently is certainly the norm,” said Frangione. “The parents, often times, think they are doing something in their child’s best interest but they don’t really know how the child or children are being cared for, to what extent visitation will look like and how the agencies will help better the primary families so that reintegration can ultimately happen. Customary care becomes the focus as opposed to customary care with a focus on reintegration.”

He said agencies and nations call it “culturally appropriate” when that’s “not often” the case, according to his experience, such as when Kanina Sue Turtle died in a Sioux Lookout foster home owned by Tikinagan with a “live-in parent” who was hired to be there on a contract-basis. The same goes for Amy Owen, who died in a non-descript two-story home on the outskirts of Ottawa that included some trips to a local Indigenous centre.

Dilico, in Frangione’s experience, is the most difficult to deal with on files.

For one, Frangione said Dilico forces him to review case files at their office while being watched, when all other agencies send the files by email. This is also known as disclosure, a basic evidentiary procedure in the Canadian court system where the Crown provides the evidence against the accused in a timely manner. The same applies to child welfare.

He also had a case recently where a parent challenged a customary care agreement and Dilico didn’t respond within five days as it is supposed to as first reported by APTN. Dilico ended up returning the children without a fight, said Frangione.

APTN tried to get Dilico to go on the record for this story but after several conversations with Darcia Borg, its executive director, it never happened. The content of those conversations were off the record.

Watch Kenneth’s story Death as Expected:

The first conversation with Borg was in person because this story pulled APTN back to Thunder Bay in early August to find Alicia Jacob.

Jacob attempted to sue Dilico over the death of her son, Talon Nelson, on October 29, 2013.

Talon was three months old when he died in a crowded crib of a Thunder Bay foster home. The coroner would call it an unsafe sleeping arrangement, however no one was ever charged. The foster parent was a registered nurse.

“Undetermined cause of death, too many stuffed animals in a f***ing sleeping environment,” she screamed when speaking to APTN when we found her in early August.

This is child welfare in northern Ontario at its worst. A baby is dead and the mother lost on the streets.

“I never used to be like this … I have so much anger,” Jacob sobbed.

After the infant’s death his father Nazareth Nelson hit drugs hard. People say he was on some heavy street drugs brought in from Toronto gangsters the night he killed a man in 2017. He was later convicted for the murder of Burt Issac Wood.

Their lawyer was Christopher Watkins, and just a few months after the lawsuit was filed it was dismissed without costs. During this time Watkins was struggling himself and the Ontario law society suspended his license back in 2018 due to “a history of failing to attend court appearances in criminal proceedings dating to at least 2012.”

Watkins issued a public apology saying personal and health problems were to blame.

APTN emailed several of Watkins’ email addresses seeking clarification on why the lawsuit was dismissed.

This was the only response verbatim: “Hi this up and working and interesting journey to convey. Christopher.”

APTN never heard from him again.

Undetermined cause of death is when there is no clear evidence to confirm it. Babies that suffocate often don’t leave any evidence even if the sleeping arrangement is unsafe and, in Ontario, 22 Indigenous children died in this manner between 2013 to 2017.

“The deaths of infants is very challenging ones in death investigations generally because in sudden and unexpected deaths of infants, so infants under one, we often unfortunately upwards of a significant percentage of time do not find a cause a death,” said Dirk Huyer, the chief coroner of Ontario, who is largely seen as someone trying to make incremental change within the system.

“The truth is we don’t know and use a term undetermined which is kind of a harsh term but it means we don’t know. So we say we don’t know. We say the environment may have been a factor but we don’t know if it was a factor.”

(Breanne LeClair said getting her late son’s autopsy report and seeing ‘undetermined’ added insult to injury. Photo: Kenneth Jackson/APTN)

Breanne LeClair’s late son Kyler was one of the 102 and also undetermined.

Kyler was in what’s known as a kinship out of care agreement.

That means an agency was involved but he was living with relatives.

In his case, the agency ordered Kyler to live with his Caucasian father.

That was in January 2014 just days after he was born.

To this day it’s difficult for LeClair to talk about.

“My ex and his mom agreed to sign for the kinship so if you sign this document they’ve agreed to let you go with them and the baby or we’re going to give him the baby,” she said, breaking down in tears.

That living arrangement broke down quickly and she had to move out, forced to leave her Kyler behind.

Then one morning her phone rang.

“It was somewhere around nine in the morning my phone rang. I had my ex’s number saved as don’t answer but I figured I should answer and all he said is the baby turned blue. We are on our way to the hospital. I was like what do you mean the baby turned blue?” she recounted.

As LeClair rushed to hospital she called her case worker.

“I just screamed into the phone and I told her if anything happened to him this is on you. This is your fault. You made this decision,” she said.

Then she entered the room and saw her baby on a hospital bed.

“I could hear machines that are just beeping, there’s people running, moving over each other, there’s like three or four detectives in the room, there’s like five or six nurses and the doctor. I wasn’t really aware of what was going on until I saw him,” said LeClair.

Kyler was gone.

His father left him on an adult-sized bed to take a shower.

He was found lifeless 30 minutes later.

Breanne and her family tried to hold someone accountable.

The case worker wasn’t a licensed social worker so they couldn’t try to hold her to account at the Ontario College of Social Workers.

Then finally the coroner’s report came nearly a year later.

The coroner found the sleeping arrangement unsafe but ruled the death undetermined.

“Where no one has to face anything,” said LeClair.

No one appears to have ever faced anything in any of these deaths.

(Dirk Huyer, right, is the chief coroner of Ontario and says despite exhaustive investigations some deaths involving babies have no cause of death. Photo: Jason Leroux/APTN)

Even the 102 is the lowest number available.

If the child was from on-reserve then it stands to reason their race would be easily identifiable.

“You correctly point out that if children were receiving services from an Indigenous agency, then it is pretty easy to identify them as Indigenous however; we do not systemically obtain race or identity so we do not effectively obtain this information,” said Cheryl Maher, spokesperson for the chief coroner. “For children and youth living off-reserve and being served by mainstream societies they would be identified by the service or family of the deceased child. If the child or youth is (First Nation, Inuit, Metis) but not identified, then we have not included them in statistics.”

However, the “mainstream” agencies weren’t required to start collecting race-based data until February 2018, through a policy directive, and to this day the Ontario government doesn’t have a clear picture of how many Indigenous children are in care or involved with an agency in the last 12 months.

That’s partly because the system designed to capture the data hasn’t worked properly. It’s called the Child Protection Information Network (CPIN) and it’s a database aimed at tracking the children in the system. However, several non-Indigenous agency directors told APTN issues of duplication have been a problem where the same child is listed in two regions and counted as two individuals.

The province has also been slow to provide a standardized process for data entry. Several of the 38 agencies required to use CPIN only began in recent months despite the system being several years old.

It gets worse.

The former Ontario Liberal government didn’t just make it policy to collect identity-based data; it also passed a law in 2017 making it mandatory for the provinces 38 non-Indigenous agencies. But not until July, 1, 2021.

Indigenous child welfare agencies have refused to be on CPIN, and the ministry is still “engaging with Indigenous partners,” according a spokesperson.

If you ask the Ontario government how many kids are in care they will say this: “There were 12,651 children and youth in the care of children’s aid societies and in customary care (in 2018/19 fiscal year), including: 1,569 First Nations children and youth determined to be in need of protection were in customary care arrangements.”

These numbers are not correct but most people wouldn’t know the difference.

When these numbers were sent to APTN we challenged the province on it. The next day it responded with a similar statement but with a small change: “In the 2018-19 fiscal year, there were on average 12,651 children and youth in the care of children’s aid societies and in customary care.”

“On average” was italicized by the government.

“Due to admissions to, and discharges from, care the number of children in the care of Ontario’s 50 children’s aid societies fluctuates. Societies therefore provide the ministry with the average number of children in care over the course of a year. The average number of children in care is an average of the total number of children in care at the end of each month, from March 31 of the previous fiscal year to March 31 of the current fiscal year,” said a ministry spokesperson in an email.

Simply put: the system isn’t able to give a single-point-in-time number because that number can change day to day. It’s just not tracked that way and yet, unless challenged, the government misleads the public and reporters.

Things have only gotten worse under Premier Doug Ford according to Irwin Elman, the former Ontario child advocate.

The Ford government closed Elman’s office as the Progressive Conservatives’ first move on child welfare after the special panel report came out saying the system was a mess.

Its doors closed earlier this year; the ombudsman’s office now handles some of Elman’s former responsibilities.

The closure also came while the advocate’s office was working on 27 investigations, mainly into foster homes, including the home Tammy Keeash was last in before she died.

Almost everything APTN has written in this story does not come as a surprise to the former advocate.

“To be aware in many ways is to be in a constant state of outrage,” said Elman, Ontario’s first and last child advocate.

But when Elman’s office first opened about a decade ago he noticed something.

“Every three days – Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday – a child connected to care dies. Thursday, Friday, Saturday, a child’s died connected to a system that is meant on all our behalf to protect them,” he said.

He’s right.

During the five-year period between 2013 and 2017 the coroner lists 541 deaths involving child welfare and 102 were Indigenous.

Indigenous people represent less than three per cent of Ontario’s population.

So when that child dies they are more likely to be Indigenous.

And, again, that’s no surprise to people who have been fighting for these kids, like Cindy Blackstock.

It’s largely because of Blackstock that the human rights tribunal found Canada guilty of systematically under-funding on-reserve child welfare.

“The tribunal found that Canada’s First Nation child welfare funding across the country and Ontario was discriminatory in January 2016 and ordered Canada to stop but it did nothing until the tribunal issued a subsequent order in February 2018,” she said.

Based on that order Canada retroactively provided funds to 2016. To date, just in Ontario, the feds have “reimbursed” approximately $135 million.

But you can’t go back in time to save any of these children, no matter how much money you throw at it.

“Children died waiting for Canada. That’s the problem with them saying, oh well, we are making good first steps … be patient with us. The reality is that children’s lives are really on the line while we’re waiting and many more children lost their lives during the time we litigated this case and for the many years before when they had a chance to fix it,” said Blackstock.

The Trudeau government also narrowly squeezed in new legislation for Indigenous child welfare last spring.

But the day Indigenous Services Minister Seamus O’Regan tabled the bill he didn’t have a lot of details – particularly when it came to money.

This worries Blackstock who says it’s another example of the feds not taking funding child welfare seriously.

“My worry is that we really need to make sure Canada isn’t using C-92 as an escape clause for its fiscal responsibilities to First Nation children,” she said. “Sure, it recognizes jurisdiction. But no money to implement your programs. And you’re dealing with families who are dealing with the weight of multi-cultural trauma from residential schools, from colonialism, starvation polices, taking of land, taking of resources, ’60s Scoop, child welfare, all things Canada was directly involved with.

“And they are going to hand it over to First nations and say good luck. I think that is wrong.”

Tikinagan didn’t respond to APTN and Payukotayno asked for questions to be sent by email but didn’t give any answers.

Meanwhile, in August the Ford government put out a call for submissions on how to improve the child welfare system in Ontario.

Earlier this month the human rights tribunal ordered Canada to pay each First Nations child who was in care, or guardian, $40,000.

As for the title of this story, “Death as Expected” comes from standardized forms, reviewed by Professor Kim Snow, that an agency worker completed when a child in care died of natural causes during her investigation for the former child advocate.

“It was the only words written for the reports on the kids that died as a result of medical fragility,” said Snow.

But many of these deaths, from the suicides to the undetermined, were expected said Blackstock.

“It wasn’t an accident,” she said.

– Additional reporting by former APTN reporter Martha Troian, who helped track the number of deaths and APTN reporter Willow Fiddler, who pulled documents from the Thunder Bay courthouse.