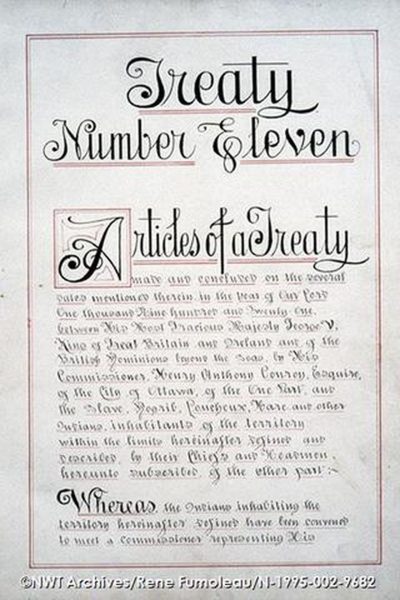

Treaty 11 was the last to be signed in Canada’s system of numbered treaties.

It was supposed to be an agreement of “peace and friendship” with the Dene of the Northwest Territories.

But it turned out to be anything but.

The Dene learned – once the document was translated into their dialects many years later – the government had seized ownership of the territory’s lucrative natural resources and wildlife.

And the abundant land.

The origin story was shared as part of the 100-year anniversary of the treaty during the summer of 2021.

Treaty making based on sacred Dene legends

To understand the Dene foundations of Treaty 11, it’s important to understand their legends, and Kweteniɂaá, Great Bear Rock in Tulita, Northwest Territories is a good place to start.

“This place is very historical and sacred,” said James McPherson. “It is where the story of Yamoria and the two giant beavers starts.”

McPherson relays a creation story of monster beavers who terrorized the Dene until the creator sent down two giants, Yamoria and Yamozha.

“Yamoria seen the beaver, he shot some arrows just in front of the mouth of the Bear River, and to this day – it could be 20,000 years ago – those arrows are still sticking in the ground,” he said.

Once the beavers were shot, Yamora got to skinning the animals at what today is known as 12-Mile Creek, an area famous for its red sand.

At the first point past Tulita, Yamoria cooked the beaver. As McPherson explained the coals were so hot from the beaver fat, smoke from that area can still be seen to this day.

As a tourism operator from Tulita, and as someone honouring Dene laws, he often shares his knowledge with others.

Mackenzie River

“There’s a lot that can happen with the Mackenzie River. It’s so powerful; it doesn’t take long for someone to lose their life and we value life a lot,” McPherson said. “So we feel that we should share that with everyone.”

This summer, hundreds of people across Denendeh gathered to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the signing of Treaty 11.

In the Sahtu region, this included a multi-day celebration complete with speeches, drum dances, games, stories, country food and more.

McPherson celebrated after spending weeks on-the-land by working with others on a moose skin boat – a project he contributed in blood, sweat and tears.

“It was always a tradition of the people. Before there were villages, everyone was scattered out on-the-land. Everyone would come to the gathering – it was a big thing. The gunshots [in celebration] happened when the moose skin boats came in with the people of Délįnę, arriving to celebrate the signing with the people of Tulita,” he said.

Norman Yakelaya, national chief of the Dene Nation, recalled how his grandmother, Harriet Gladue, told him about his grandfather, Chief Albert Wright, signing the treaty.

“He came home and they said, ‘The government wants to make treaty – want to make a payment’, and that they were talking about making a payment for the treaty,” Yakelaya said. “My grandmother said ‘What’s a treaty?’ And he said, well, ‘When the white man comes down the river, we’re not to war on them, we’re supposed to make them feel welcome.’”

Albert Wright wasn’t a chief by birth; rather, the church and state made him one by design.

When the treaty party left Ottawa to travel up the Mackenzie River for negotiations, they had already drafted the treaty documents.

Yakelaya said he has always questioned the motives of the Canadian government leading up to the signing.

“We know that in 1914 they already started working at the Norman Wells oil field and they soon discovered with that there’s a lot of oil and that could help the national debt in Canada,” Yakelaya said. “The government knew that to get all the resources they would have to clear the path and so seven years later they made a treaty. My question is ‘What were they doing in the seven years?’”

For nearly four decades after the signing, the Dene were not privy to the contents of the treaty.

Yakelaya told APTN News that in 1969, when the colonial governments’ version of the treaty was finally translated and read to an assembly of Dene chiefs, their jaws dropped.

“A hundred years ago, the people did not know the value of our economic resources on the land, we only wanted to survive in peace. And the federal government – they knew they could use it for their own benefit.”

In the infamous case of Paulette et al. v. The Queen, more than a dozen chiefs from the Mackenzie Valley challenged the federal government to recognize Indigenous ownership of some 1,165,494 square kilometres of territory stretching across Denendeh.

They filed a caveat and argued that they never surrendered their rights or land.

“You have the mountain here with street Beaver skins and the two arrows in Bear River... That’s sacred to go to protect that, and that’s what the elders were talking about."

Norman Yakelaya Tweet

The historical case uncovered evidence depicting X’s on the Treaty 11 document where signatures would have been required. After all, Indigenous signatories did not read or write in the English language.

It was paramount for the Dene to continue their way of life fishing, hunting and trapping.

While federal and territorial governments imposed many restrictions that dispossessed them of their land, Yakelaya said the Dene know the real history of the deal they made, guided by a “higher authority.”

“You have the mountain here with street Beaver skins and the two arrows in Bear River. We have the smoke down here and the river. That’s sacred to go to protect that, and that’s what the elders were talking about. We made that treaty based on those sacred legends on our land,” he said.

‘Dene resilience, Dene brilliance’: Community celebrates treaty centennial

For Paul Andrew, Tulita is sa koe – his home.

He’s Shita Got’ine Mountain Dene, a respected Elder, a knowledge holder, and a lively emcee for a crowd raring to drum dance into the wee hours.

One hundred years ago, Andrew’s ancestors were gathered in Tulita, what was then known as Fort Norman, Northwest Territories for the signing of Treaty 11.

Fast forward to July 2021, and the roughly 500-person community of Tulita doubled in size for a weekend-long 100-year anniversary celebration.

“For the Dene people, giving your word at that time was considered almost sacred."

Paul Andrew Tweet

What I celebrate more than anything else is our version. That’s why I’m here, because of our elders,” Andrew said. “I’m celebrating Dene resilience, Dene brilliance and the amazing people.”

In the summer of 1921, his relatives were travelling in the western mountains and stumbled upon a wooden post where a sign said a treaty had been made.

“For the Dene people, giving your word at that time was considered almost sacred. They came into town to celebrate treaty signing because of the sacred event that had taken place,” he said.

Andrew explained to APTN News that Dene elders questioned why the Crown wanted a treaty in the first place. But in the end, they were persuaded to sign after the Roman Catholic church’s representative, Bishop Gabriel Breynat, promised it was merely an agreement for peace and friendship.

“’Since he’s [Bishop Breynat] a man of God he can’t lie. We’ll ask him and see what he says.’ So they asked the Bishop and the Bishop said, ‘Yeah, they’re [the Crown] here to take care of you two, here to live with you, and you will always live your life the way you have been,’” Andrew said.

But it was a broken promise.

What the Dene thought they’d signed and what the colonial government had penned were in stark contrast.

Andrew said elders who were present for the Treaty 11 signing were not privy to the information in the official document until the late 1960s, when it was transcribed from English into Dene dialects.

“I still remember the reaction from some of the elders. Most of them were shocked. First of all, they couldn’t believe that anyone would give up land. We’re talking about one square mile for a family of five,” he said.

A way of life was shifting for the first peoples of the land.

Soon after the treaty was penned, a territorial government was born to oversee oil exploration, without consent from any Indigenous groups.

“When I was Chief in the early 1970s for example, somebody would walk into my office and say ‘A bulldozer ran over my trapline’ or ‘What is going on?’ Somebody somewhere was issuing permits that we didn’t know about,” Andrew said.

Settler religion was also forcibly introduced into communities across Denendeh.

Nowadays, the community has blended its own traditions with western culture.

Sister Celeste Goulet, who has lived in the hamlet of Tulita for more than 40 years, told APTN about her experience of moving from Toronto and being welcomed in peace and friendship.

“I often said they knew Jesus even before Christianity introduced him. They had a connection, especially to the land. Their spirituality is so connected to the land and nature. They knew there had to be something, a creator,” Goulet said.

“A hundred years ago they were playing handgames. Today, it's still the same, nothing is going to change. It makes you proud."

Huey Kenny Tweet

Longtime chief of Tulita, Frank Andrew, also chooses to celebrate what his ancestors negotiated on behalf of future generations.

“As Dene, we have treaty rights that cover our medical as well as our education. Which means that our elders signed a good deal for us,” Frank said.

This summer, many Sahtu, Dehcho, Tłı̨chǫ and Gwich’in communities – where Treaty 11 was signed held anniversary commemorative events.

Huey Kenny travelled by boat from Délı̨nę to Tulita to participate in the three-day Dene handgames tournament.

“A hundred years ago they were playing handgames. Today, it’s still the same, nothing is going to change. It makes you proud. You entertain people and they’re so happy you’re there,” Kenny said.

Many elders, including Andrew, participated in the games. In-between matches the captivated crowd listened attentively as knowledge holders shared the complex history of Treaty 11.

But as Andrew put it, it’s the Dene’s version of history that his community honoured.

“When they came up with the deal, they were not thinking about, ‘How am I going to benefit out of this?’ They were talking about ‘What is it going to be like for our grandchildren?’ That’s the kind of thing that I think is really important for us to remember now,” he said.

Following the ancestors’ trail on the Sahtúdé

Cyre Yukon glanced up from her clipboard for one final roll call, to cross reference supplies and participants.

Bringing anyone out on the land entails a fair share of organization and bush skills, let alone a group of 44 with varying experience levels travelling down the mighty Sahtúdé – Great Bear River.

But that’s exactly what the Délı̨nę Got’ine Government (DGG) did as 40 community members paddled the 135-km stretch of river from Délįnę to Tulita, Northwest Territories, to mark the 100-year anniversary of the signing of Treaty 11.

“This year, we wanted to join in with the canoes to support the celebrations, and especially arriving by canoes because it comes from our traditional ways of travelling back in the day,” said Yukon. “To show our support and for our friendships between each community [in the Sahtu region].”

Délı̨nę is home to roughly 500 Sahtúgot’ine Dene and Métis.

Located on the shores of Sahtú – Great Bear Lake – the pristine lake is known as the “water heart” of Denendeh, a heartbeat connecting all living things throughout the traditional territory.

“The goal since we started was to get people more engaged on the land like our ancestors used to. "

Cyre Yukon Tweet

As chief operating officer with the DGG, Yukon has organized and participated in community trips over the last three years.

“The goal since we started was to get people more engaged on the land like our ancestors used to. We plan on going to different locations to learn about the different areas around the lake.”

Every paddler has deep familial connections along the river.

“Bennett’s Field is where my family kind of grew up. They used to camp out there,” she added. “It brought back the stories that my dad and aunties would tell me about that place. There’s more I want to learn.”

Another objective of the historic trip was to provide cultural learning opportunities for the next generation.

“Bennett’s Field is where my family kind of grew up. They used to camp out there,” she added. “It brought back the stories that my dad and aunties would tell me about that place. There’s more I want to learn.”

Another objective of the historic trip was to provide cultural learning opportunities for the next generation.

Kayden Neyelle was one of the youngest participants at 16, and jumped at the opportunity to take his first overnight trip on the river.

Although he wasn’t one for the spotlight, he told APTN News he was proud to help in the feeding of the fire ceremony.

“Passing the rapids were scary, but we were told to hold the gunwale and keep going. Then I liked that the drummers were waiting for us in Tulita to celebrate and shoot guns,” Neyelle said.

“I think they [the federal government] has a lack of understanding on how we live up in the North, and especially in our community."

Cyre Yukon Tweet

The legacy of Treaty 11 is complex and has impacted all Indigenous peoples in an area more than double the size of Germany.

In the summer of 1921, Canada’s colonial government sent a Treaty 11 party down the Dehcho – Mackenzie River.

In an effort to sign the last of Canada’s numbered treaties the party made eight stops into communities.

The Treaty 11 party promised a nation-to-nation relationship, but for the dozen-plus Gwich’in, Sahtu, Decho and Tłı̨chǫ who met with the party – the Dene’s version of the deal doesn’t match with what Canada would later claim.

Yukon expressed her opinion to APTN on how the federal government had always viewed Treaty 11 territory as a singular land mass that contrasts with the Dene’s understanding of the land, which knows no borders and has distinct and special meaning for each family across the Sahtu.

“I think they [the federal government] have a lack of understanding on how we live up in the North, and especially in our community,” she said. “You can see paddling from Délı̨nę to Tulita, the big differences in the environment, even though we’re so close our cultures are so different.”

“I just want to say it is a very historic day. July 15 is 100 years since they signed Treaty 11."

Délı̨nę’s Chief Leroy Andre Tweet

Sahtúgot’ine oral history over the last 100 years has held firm how Indigenous elders who witnessed the treaty signing were under the impression they shook hands on the agreement of peace and friendship with the white man.

In reality, the colonial government used Treaty 11 as a means to dispossess them from their land.

The Crown staked illegitimate claim over oil reserves in the Sahtu and imposed restrictions that limited traditional harvesting.

Délı̨nę’s Chief Leroy Andre spoke about the broken promises throughout the weekend’s commemorative events.

“I just want to say it is a very historic day. July 15 is 100 years since they signed Treaty 11,” Andre told the large crowd that had gathered for a feeding of the fire at the graveyard the morning of the trip.

Like Andre, the Sahtu focused not on the colonial fallout from Treaty 11, but on Indigenous resiliency over the last century.

“My grandfather Andre Andre was 19 years old when [the] treaty was signed in Tulita. He was there and witnessed all the discussions that happened,” Andre said. “We also now signed a land-claim agreement and signed a self-government agreement. The last 100 years, you guys are representing Sahtu Dene people.”

After a long but rewarding few days Yukon’s work was done. While she didn’t take any credit for the trip she left the weekend feeling proud.

“Having the DGG now, and even before self-government, we have always had that independence. And nothing is possible without that community as a whole.”

Délįnę paddlers make historic canoe trip

It’s an exhilarating feeling being greeted by families, leaders and traditional drummers after canoeing 135 km down the Sahtúdé – Great Bear River – in the Northwest Territories.

But for this group the journey is just as important as the destination.

It’s the first time Verna Taneton is canoeing the river with her son, Troy.

“We usually pay the water, and the land you feed the fire to be safe, and the water tobacco, matches or coffee – whatever leftovers you have, so we will have a safe journey to get to the place we want to be,” Taneton said.

“In the next 100 years, I want to see all of the Aboriginal people talking their tongue and showing respect for the land and the water.”

Verna Taneton Tweet

The pair is accompanying 40 others paddlers making their way from Délįnę to Tulita to participate in the 100-year anniversary marking the signing of Treaty 11.

“It’s a wonderful experience so far! My grandparents, they brought me on-the-land everywhere, trying to make me find myself and survive,” Verna said. “In the next 100 years, I want to see all of the Aboriginal people talking their tongue and showing respect for the land and the water.”

The Sahtugotine have been preserving traditional knowledge by upholding elders like Jimmy Dylan, who was born on-the-land 40 km north of Tulita.

Yamoria Trail

At 81 years old, he’s full of wisdom to share.

“This is Yamoria trail, he made this journey for all of us. So if you are having a bad feeling about yourself, this is the time to get rid of it,” Dylan told the paddlers at the mouth of the river.

He shared stories and guided the participants, following the channels he’d learned from his father and grandfather.

“When I started travelling alone, I had to remember where we had travelled. When he [Dylan’s father] was gone I took over. Now at my age I am training these guys. They are going to take over; they are going to be my hunters,” he said.

It took the group two long days to travel down the river. But before outboard motors, families would have taken double the time to collectively travel up the river back to Délįnę.

“When they’d leave Tulita some would go ahead, so they would have to wait for one another – either one or two weeks,” Dylan said. “Coming back up the river, you couldn’t paddle against it so they had to walk from Tulita all the way back with long lines pulling their boats.”

Sidney Tutcho sat in the bow of Dylan’s boat wth binoculars in one hand and a walkie-talkie in the other.

He interpreted Dylan’s messages in Sahtúgot’ı̨nęk’ə gokǝdǝ́ and relayed them to the participants.

“I believe, as of right now, my generation and the younger ones aren’t fluent. They’re sometimes embarrassed to speak because they’re afraid to mispronounce things,” Tucho said. “I don’t speak as much, but I am just trying to bridge the gap so we don’t have miscommunication to a point where we don’t understand them no more.”

The trip was good medicine for youth like Danielle Takazo.

“That’s our lake, that’s our water, that’s our land. We were there for thousands and thousands of years. Our ancestors are buried all around,” Takazo said. “We do encourage visitors and welcome people to come so we can show them what we see and what we feel. Just know it’s us and it’s ours.”

Takazo viewed the commemorative activities as an opportunity to teach the next generation about the the Dene’s role in Treaty 11.

“I don’t know much about it [Treaty 11 signing] or as much as I would like to. Is it taught in schools? The awareness in history is weak right now. I think it is important that we are informed somehow,” she said.

Just like Sahtugotine elders who negotiated for health care, education and supports during the signing of Treaty 11, Délįnę Got’ine’s government (DGG) has taken care of its own.

In 2015, they signed a self-government agreement, one of the first communities to do so in the N.W.T. And they continue to build off that momentum.

Takazo just landed a job as a coordinator for Délįnę First Youth Council.

“We [the youth council] are going to be changing history,” Takazo said.

It took teamwork to go through the 11 km stretch of rapids.

For Grand Chief Wilbert Kochon, of the Sahtu Dene Council, it was time spent talking to the land and receiving any help needed from the land.

“I’ve never been on the Bear River before. My grandmother is from Délįnę and I really wanted to check the river out,” Kochon said. “It’s kind of a personal journey for me to do for young people, for some people that are sick.”

Kochon said his elders told him “when you live on the land it’s your livelihood and you will never starve.”

“When we signed [the] treaty, it wasn’t about money or giving up the land; it was a peace treaty,” Kochon said. “Everything is colonized right now, even the territorial government. Even though they signed UNDRIP [United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples] you see it happening amongst themselves and amongst Indigenous people.”

While this summer marked 100 years since the signing of Treaty 11, Kochon and the rest of the Sahtugotine canoeing also kept count – each time they dipped their paddle in the water.

One hundred years later, they followed the same trail as their ancestors from Délįnę to Tuilita and arrived on the shores in peace and friendship.

“I would say 100 years to celebrate the past leaders, not really how government treated us. I think about the leaders that have got us this far. Elders that are still here and we are doing a lot of things better because of them signing in 1921,” he said.