Rooster Town:

The story of an urban Métis fringe community

on the outskirts of Winnipeg

But between 1901 and the late 1950s, it was a tight-knit community of Métis families in Manitoba that banded together in the face of dispossession by the government and non-Indigenous settlers.

Rooster Town, also known as Pakan Town, sprouted up on the outskirts of Winnipeg – but it was not alone.

There were similar Métis fringe communities across the Prairies and in British Columbia during this time, though they have been largely ignored or forgotten by historians and geographers.

“They were everywhere,” said Evelyn Peters, a former professor of Urban and Inner-City Studies at the University of Winnipeg and co-author of the book Rooster Town: The History of an Urban Métis Community, 1901–1961.

“I would venture to say there were probably at least 100 of them in Canada. There were 26 in Manitoba.”

Research from 1959 by social scientist Jean H. Lagassé, which was commissioned by the Manitoba government, listed 25 other fringe communities in the province, with only Pine Falls and St. Eustache having a larger population than Rooster Town at the time.

Lagassé’s research mentions the names of some of these Métis fringe settlements in the province, including Bannock Town, Tintown, Smokey Hollow, Melonville, and others.

But what caused these communities to begin forming across the prairies?

The story begins with the Manitoba Act of 1870.

Though the population fluctuated over the years due to the First World War and the postwar depression, Rooster Town reached its maximum population of 250 people in 1946.

The Manitoba Act of 1870

But according to the book Rooster Town, delays in distributing these lands to the Métis often spanned decades, while non-Métis settlers received much of the prime parcels of land.

Oftentimes, the lands given to non-Indigenous settlers had been initially promised to the Métis or their ancestors.

When land grants were given to the Métis, they were often scattered across large distances rather than concentrated, making it difficult for Métis communities to stay together.

But once again, there were long delays in distributing the lands promised to the Métis through scrip. Due to this, many Métis ended up selling their scrip – sometimes for less than half its value, according to Rooster Town.

“What Louis Riel and his people tried to do was protect Métis land and Métis communities,” said Peters. “The government in many cases failed to give Métis their land and in the meantime farmers, speculators bought up the land. So Métis were unable to recreate many of their communities, and certainly were unable to get the best land.”

“And one thing where this really was relevant to the early origins of Rooster Town was when we checked a record of all the Métis who received land and the Métis who didn’t receive land, the very large majority of the people who ended up in Rooster Town had not received title to land, so they had been left out of the implementation of the Manitoba Act.”

According to Peters’ research, the delays were a form of institutionalized neglect that led to many Métis families being dispossessed of their lands.

Métis formed fringe communities like Rooster Town on the outskirts of towns and cities as a way to provide for their families by participating in the urban economy after being forced out of their previous ways of life.

The early days of Rooster Town

In 1901, the community of Rooster Town had a population of 115 people. Many of the early residents relocated from their rural parishes in the Red River Settlement to the southwestern outskirts of Winnipeg as they were dispossessed of their lands.

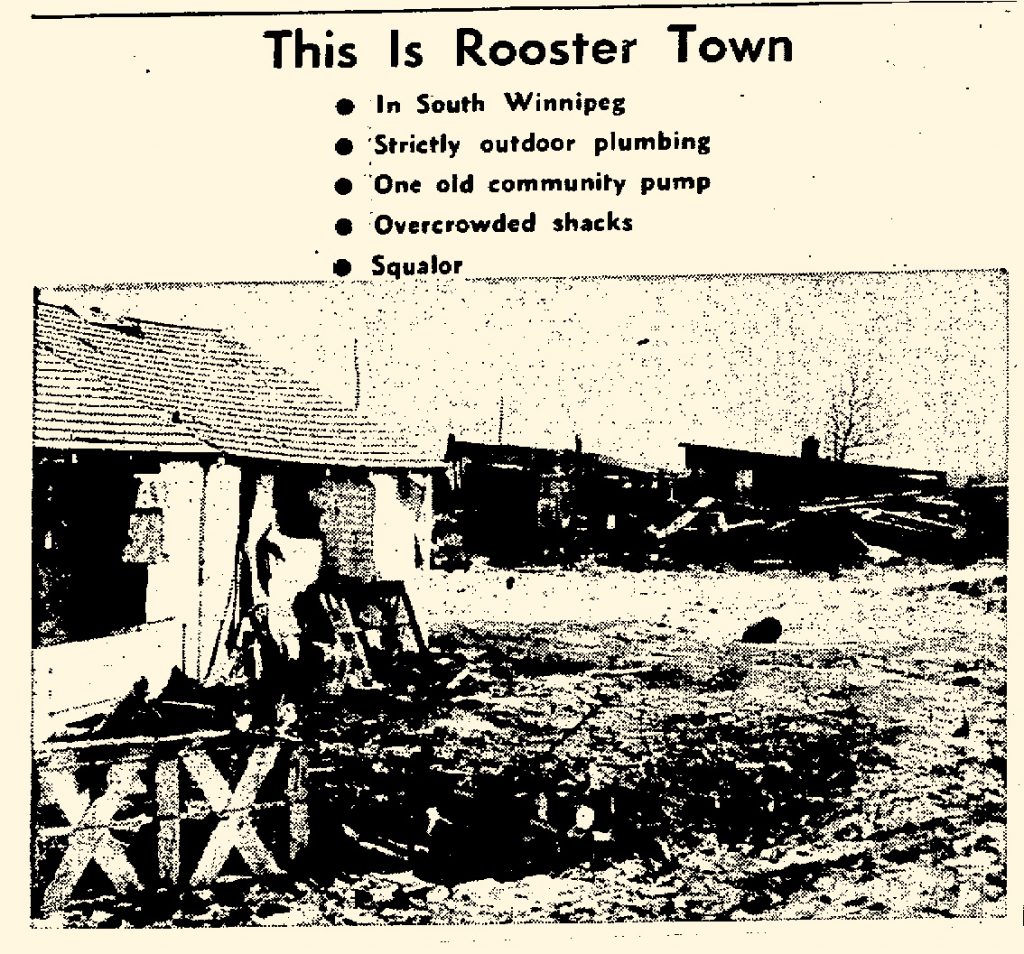

They built their own houses, and did not have access to any city amenities at the time, such as plumbing, electricity, or public transportation. Most houses averaged two rooms in size, but some families built additions on later.

Their houses were often built on city-owned land, but Métis families purchased the land their houses were built on when they could afford to do so.

Due to the lack of urban development in the area, some Métis households in Rooster Town were able to supplement their incomes with subsistence farming.

Despite being physically separate from the city, Rooster Town residents were not cut off completely from urban life. They often attended the same churches, used city services, sent their children to the same schools, and contributed to the city’s economy through their work and spending money in the city.

“They did the best they could, people fixed up their houses, they sent their kids to school, they found jobs, they tried to make a good life for their kids,” said Peters. “Their success is demonstrated by the fact that these were very large families, and so if they had all stayed in Rooster Town, really the town would be very large.”

At least half of the families living in Rooster Town at the time of its formation would go on to live in the community for the rest of their lives. Many children born in Rooster Town would grow up, marry, and start families of their own in the community over the decades.

"They did the best they could, people fixed up their houses, they sent their kids to school, they found jobs, they tried to make a good life for their kids."

Evelyn Peters Tweet

By forming their own Métis community, residents were able to preserve parts of their culture, including fiddling, jigging, and social customs.

The community continued to grow during its first decade. By 1911 there were a total of 39 households and a population of 183. Though the population fluctuated over the years due to the First World War and the postwar depression, Rooster Town reached in maximum population of 250 in 1946 living in 59 households.

According to the research in the book Rooster Town, the community’s growth suggested that it had become a recognized Métis settlement option for other Métis families that wanted to participate in Winnipeg’s economy and build better lives for their families.

“They had nine brothers and sisters, and one passed away while they were there. And then my dad went to school in the area, and it was a Métis community, very tight knit. Everybody helped everybody there.”

Sais said his family didn’t have much, but they were willing to share what they had. He recalls his father sharing a story of a stranger showing up in the middle of the night to ask for food.

“They lived close to the railway there. My dad told me of a story of an individual that was taking a train across the country. My grandmother and grandfather were sleeping, and they didn’t have screened windows, so they just had open windows.

“This man reached over and touched my grandmother and she freaked out and called out to my grandfather and he woke up. The person was saying ‘Oh please, I don’t mean you any harm. I would just like something to drink, I’m very thirsty.’ My grandfather got up, brought him into the home and my dad said they gave him a sandwich and gave him something to eat on the way and away he went,” said Sais.

“I think that’s got a lot to do with the Métis way. We just want to help anyone that needs help.”

Living near their kin and other Métis families may have also been a defence to protect themselves from racist attitudes that prevailed among non-Indigenous people in the city – but Rooster Town community members still faced racism and discrimination in their day-to-day lives. Children in school were told to not play with children from Rooster Town, as they could catch skin infections and diseases. Many Métis families who lived within city limits chose to conceal their ancestry to avoid discrimination. The way newspapers represented the community also contributed to the discrimination against the Métis residents.

Though poverty was an issue for many Métis families, the images propagated by the media did not acknowledge the context of Métis dispossession from their original lands or the discrimination they faced that pushed them to live separate from the city.

Public perception driven by the newspapers

An article in the Manitoba Free Press from 1909 wrote that Rooster Town was the “frequent scene of wild orgies” that were the subject of police reports and that raffles in the community had become “one of the most fruitful sources of trouble”.

A 1947 article from the Winnipeg Tribune referred to a Rooster Town resident’s home as a “dingy cocoon” built in a “tax free domain” that was not part of the city.

“The biggest thing my dad wanted to share that all of the negative stories in the press were wrong,” said Sais. “Where they all said they lived on welfare, they were dirty people and that’s one of the reasons my dad kept sharing his story. They may not have had running water and electricity and that, but he said that they were very good people. What the stories shared was not the truth and the city helped by sharing these stories to make it look negative, so it gave them a reason why they wanted to get rid of them.”

Though poverty was an issue for many Métis families, the images propagated by the media did not acknowledge the context of Métis dispossession from their original lands or the discrimination they faced that pushed them to live separate from the city. In addition, the stereotypes shown in the newspapers were not the lived reality of the families.

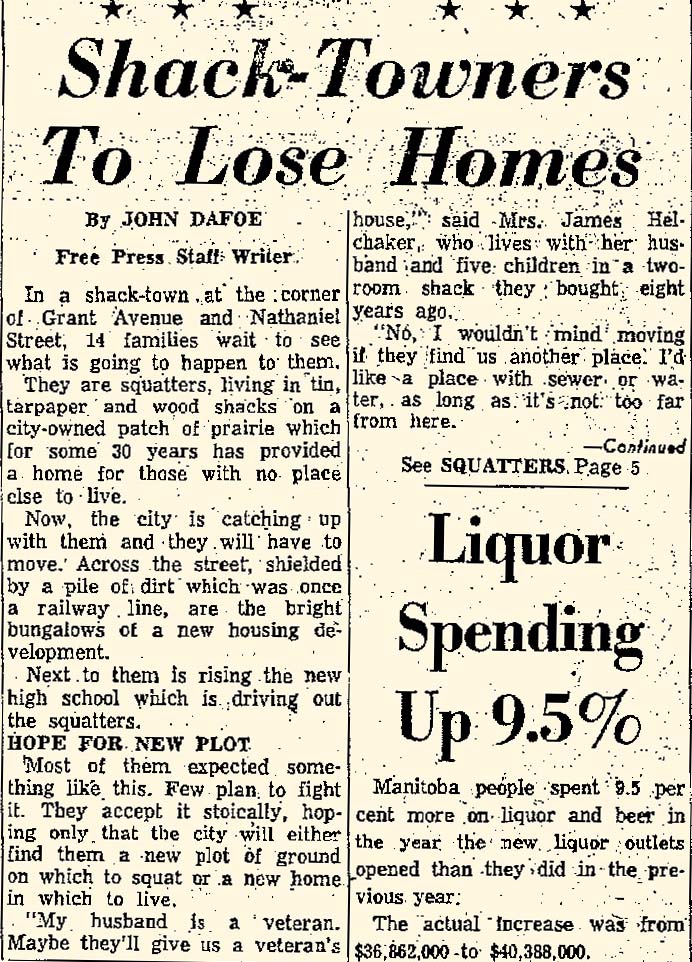

By the 1950s, when Winnipeg was rapidly expanding, it was not uncommon to see reporters prying into the lives of Rooster Town residents, knocking on doors with cameras in hand to document some of the poorest dwellings in the community.

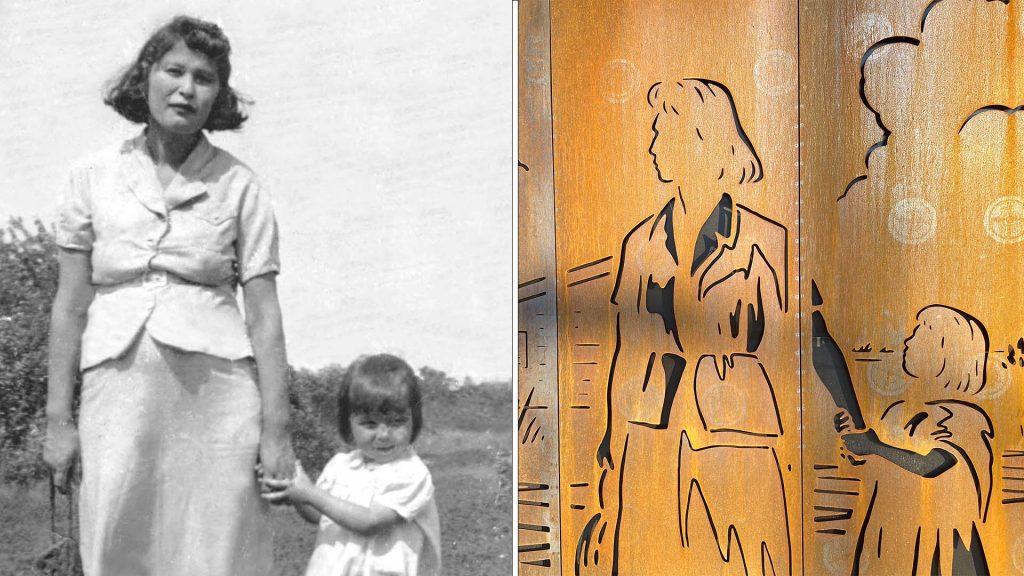

Many Rooster Town family portraits at the time showed residents that were “virtually indistinguishable” from Winnipeg residents, according to Peters.

“There had already been negative perceptions of Indigenous people living in cities for decades, and I think these reports just reinforced what people already thought,” said Peters.

By the 1950s, when Winnipeg was rapidly expanding, it was not uncommon to see reporters prying into the lives of Rooster Town residents, knocking on doors with cameras in hand to document some of the poorest dwellings in the community.

According to the Peters, these newspaper articles depicted narratives that the Métis were not able to cope with modern society in a fashion that helped to justify the community’s eventual forced dispersal. In addition, the articles embarrassed some Rooster Town residents to the point that they became reluctant to speak about their experiences to people outside of the community.

Loss of a community

New city streets and rows of houses began to encroach on the previously undeveloped areas around Rooster Town. Some Rooster Town residents were able to buy lots nearby that were connected to the city’s services, while the city pressured others to relocate to the city’s North End neighbourhood.

Many residents were reluctant to move, and in 1959 the city offered the remaining households $75 to relocate or face eviction by the month of May.

Sais remembered his father telling him the story of how his family was driven away from the community.

“In 1960, they were told they didn’t own the land anymore and the school division owned the land. They went home, told my grandfather, got a hold of one of his relatives and they went to city hall and sure enough they had given it away,” said Sais. “My grandfather actually owned his land in Rooster Town.”

After six decades, the community of Rooster Town was forcefully disbanded. Rooster Town residents lost more than just their homes. They lost the support network of their neighbours, the cultural aspect of living in a Métis community, the investments made into their homes, and the way of life they had lived – some for 60 years.

“My family went from someone who owned land and owned a home to where a whole generation went through renting and it was only in the second generation they had been able to purchase homes again,” said Sais. “They didn’t better our lives.”

In an ironic twist, by the 1960s there were newspaper articles looking back nostalgically on the community that had once existed.

Today, the land where residents of Rooster Town used to live is now largely occupied by Grant Park Mall, Grant Park High School, the Pan Am Pool, and the Bill and Helen Norrie Library.

Rooster Town's legacy

Art installations by Ian August in 2019 titled Rooster Town Kettle and Fetching Water showcase a large copper tea kettle and metal cutout silhouettes of residents fetching water. The installation honours the history of Rooster Town and acknowledges where is existed and what life was like for residents without running water.

The Bill and Helen Norrie Library opened in March 2021, and includes several elements acknowledging the community that used to exist on the same site where the library now stands. A large exterior mural made of metal shows engravings depicting life for Rooster Town residents, and the interior includes Saskatoon berry designs and Rooster Town books and artifacts

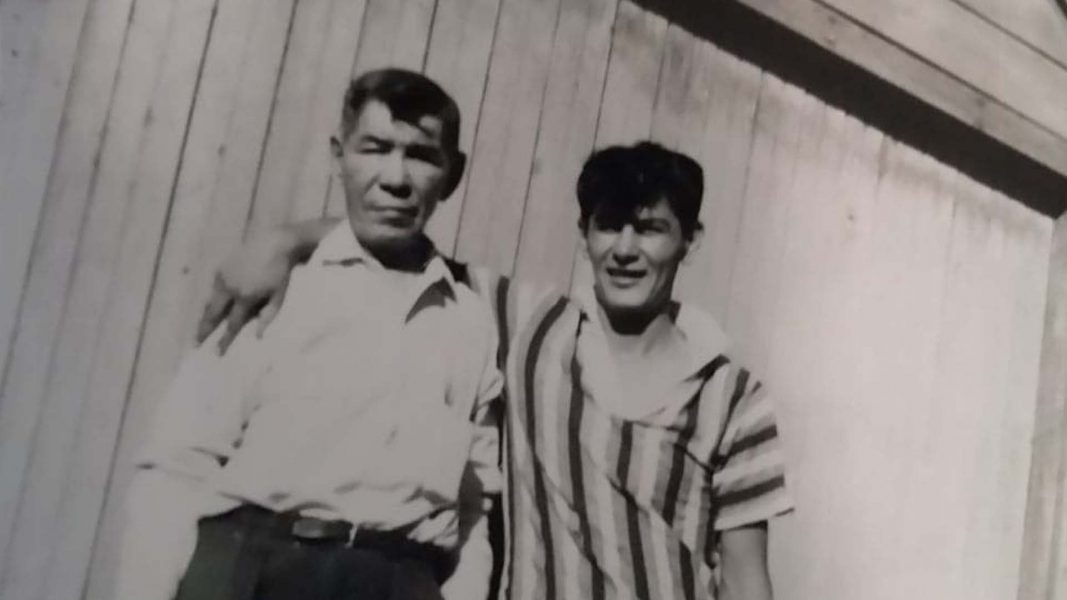

“I’m always envious of people that have photos of their families in that era, where we couldn’t afford a camera. We don’t have very many pictures, that’s one of the rare ones we have,” said Sais.

The library held meetings and consulted with Sais’s father and uncle on what they wanted to see represented in the space.

“The new library recognizes and provides educational information about Rooster Town and Pakan Town. This is something that was the result of extensive discussion and dialogue and input from the families of Rooster Town,” said Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman at the announcement of the library. “There’s a tremendous amount of recognition and education for all Winnipeggers to recognize Rooster Town.”

The story of Rooster Town is one of many.

The dispossession of Métis lands across the west and institutionalized neglect from the Canadian government led to these communities forming, and the continued colonial treatment of Indigenous Peoples also led to their eventual dissolution.

But similar to many of the darker chapters of Indigenous history in Canada, the story of Rooster Town is not ancient history – it exists in the living memory of Métis people today.

“I think it’s important for families to know where they’re from and not to be ashamed from this because they were very hardworking families that lived in Rooster Town,” said Sais.