Canada erased their First Nation from history...

Now, they’re fighting to be recognized.

Sara Connors | April 24, 2023

The Pelly Banks Government claims it was wrongfully amalgamated with what is now the Ross River Dena Council in 1956.

It’s been more than 70 years since the federal government began dismantling the former Pelly Banks band.

Despite being erased from history, its people and their descendants are refusing to fade away.

“They’re a forgotten people, they’re forgotten by Yukon,” said Erika Gilson, executive director for the Pelly Banks Government.

“We’re the living epitome, the living proof of the failings of the Federal government.”

Though not a member herself, Gilson’s husband’s family are members of the government. It’s the reason why she’s lending her voice to the fight for the Pelly Banks people.

The group is made up of former Pelly Banks band members and their descendants, though it’s not legally recognized as a First Nation in Yukon.

Despite this, the Pelly Banks people claim they are a First Nations government – a government that was wrongfully amalgamated with the Ross River Dena Council (RRDC) in the 1950s.

For decades, they’ve been fighting to be recognized as a separate First Nation.

“(The Pelly Banks) people live on the land today. They continue to live as they always have,” Gilson said. “We have a God given right to be here as anybody else.”

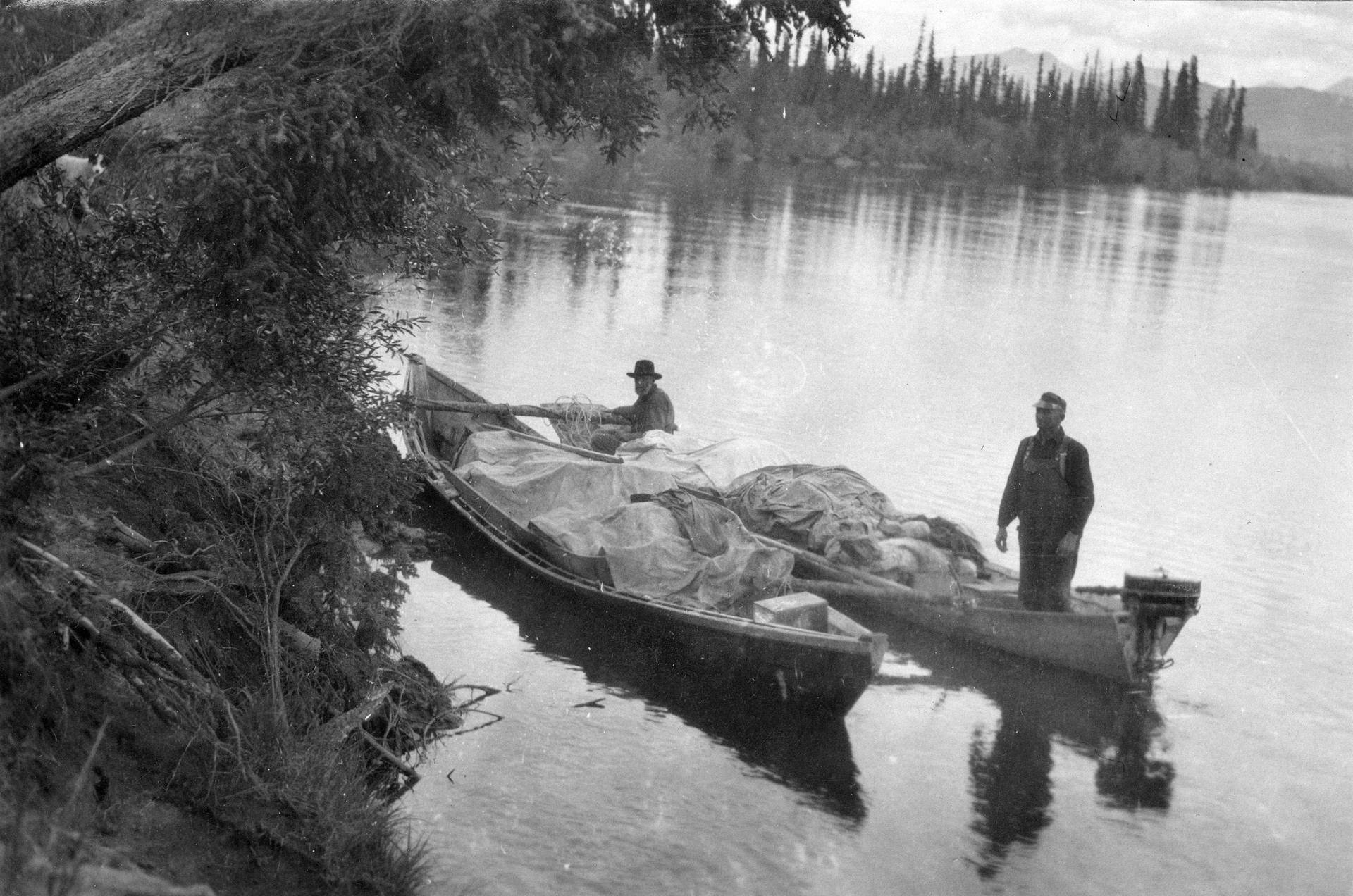

Known as gas tua, meaning “salmon river” in the Kaska language, Pelly Banks is located at the confluence of the Big Campbell River and the Pelly River around 100 km east from the community of Ross River.

According to a Whitehorse Star newspaper article from 1924, the first recorded Pelly Banks settlement was established as a trading post by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1845 near what is now the community of Ross River. Archival records show the area was named after famed Hudson’s Bay governor John Henry Pelly.

Archival documents state the post was later destroyed by a fire and abandoned. In the late 19th century, retail goods company Taylor & Drury Limited opened another trading post in the area that is now known as Pelly Banks.

Gilson said in 1946 the post was moved approximately 100 kilometers north to Pelly Lakes in order to make it easier for float planes delivering supplies to land there. People continued to live in both areas and their names are used interchangeably by members and descendants.

Documents show the department of Indian Affairs (DIA), as it was called at the time, created a band membership list for Pelly Lakes in 1951. While the documents do not state if the band list also contains membership from Pelly Banks, Pelly Lakes Band 11 was registered by the DIA in 1953.

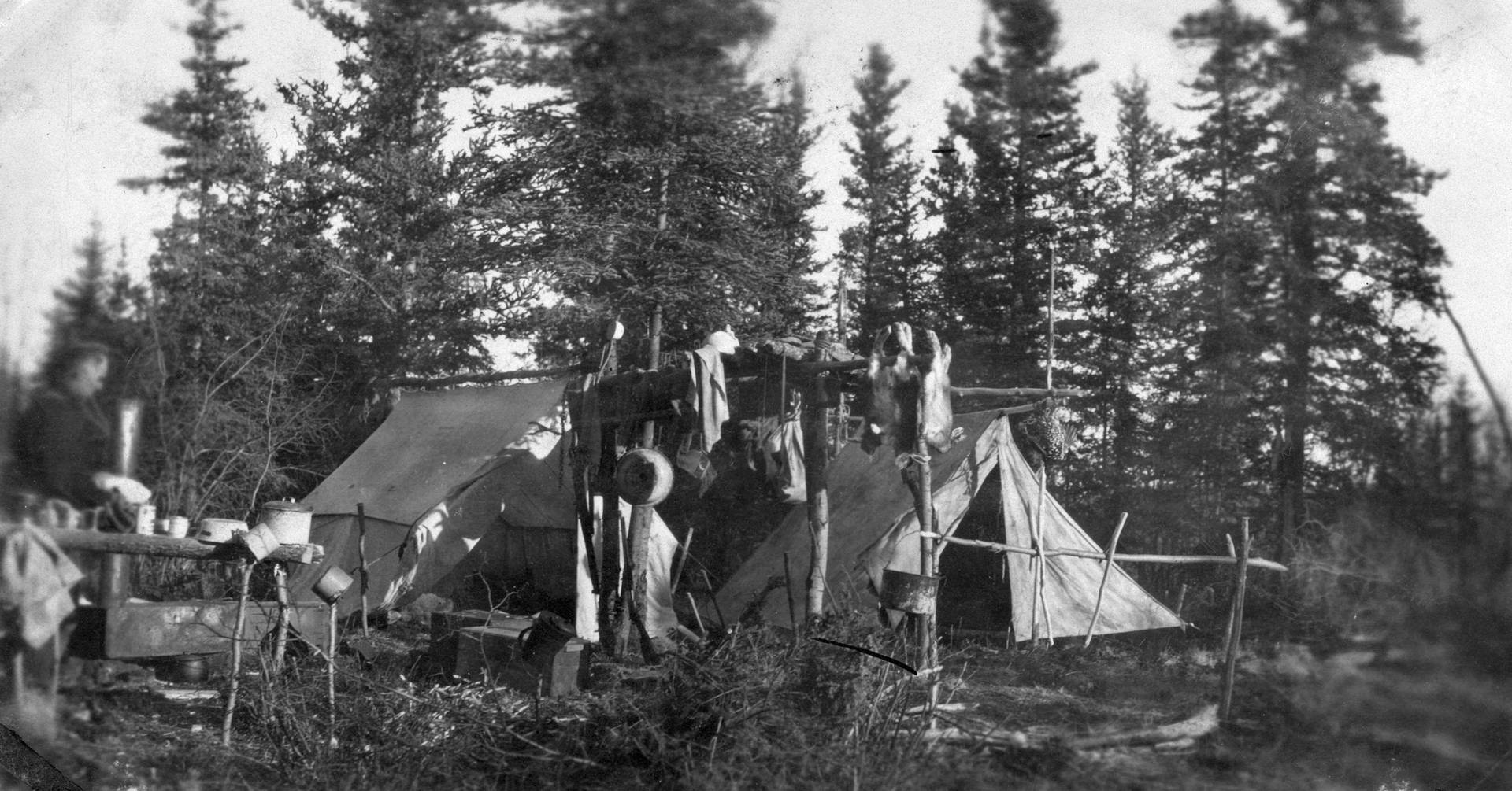

Gilson said as the Kaska living in the area were often gone hunting and trapping, membership lists are likely inaccurate, though they show as many as 20 registered family groups belonging to the Pelly Lakes band in 1953.

Elder Testloa Smith, a Pelly Lakes band member and Crow Clan leader for the Pelly Banks government, has fond memories of his childhood.

“I grew up there until (age seven). We would go live out in the land. There’s lots of places in Pelly Banks you can go out on the land and you can fish (and hunt) moose, caribou,” he said.

But Gilson said the dark legacy of residential school was the first step in dispersing the Pelly Banks people.

According to elders, in 1949, children in the community were taken away by plane to attend residential school.

From then on, Gilson said, children were often used to coerce parents into leaving.

She noted there are many stories of children attending residential school and not being returned back to their families. She said it wasn’t uncommon for families to relocate in order to be near the former Lower Post residential school in northern B.C., resulting in many Pelly Banks members to be absorbed into what is now the Liard First Nation (LFN).

“It was directly because of the residential schools coming in and stealing (the children) that they dismantled the community and they scattered the people,” Gilson said.

Though some families remained in Pelly Banks and Pelly Lakes, the trading post in Pelly Lakes closed in 1952.

In 1953, the superintendent for the Yukon Indian Agency wrote to the Indian commissioner for B.C., stating the band should be considered for amalgamation with the Ross River band, now known as the Ross River Dena Council (RRDC).

Gabrielle Slowey, an associate professor in the department of politics at York University in Toronto, said it wasn’t uncommon for the DIA to amalgamate bands for administrative purposes.

Though Slowey isn’t familiar with Pelly Banks, she noted the DIA preferred to move Indigenous communities to more central areas so they could implement provisions of the Indian Act like providing social welfare.

“Across Canada, the federal government sent in Indian agents and other federal officials to say, ‘Listen, how do we sort of maximize our strategy here and put as many Indigenous people in one space as possible?’ Just to make it easier for them to administer,” she said.

“This was sort of an expedient, judicious, cost saving measure, if you will, regardless of where the community’s geography was from or their ancestors were from.”

Slowey said amalgamation was often seemingly done at random with communities that the DIA considered similar to each other. A 1955 document from the Indian commissioner for B.C. to the DIA recommended amalgamating three bands in Yukon, including Pelly Lakes, “due to their geographical location and intermixing.”

A June 1956 DIA document further states it would be “desirable to do away with a number of bands in the southern part of the Yukon” due to a lack of what it considered organized band councils, among other things.

It goes on to say limiting the number of reserves would make the integration process easier for the department and that by moving the bands to more central areas they would be closer to roads and economic and employment opportunities.

In 1956 the Pelly Lakes band was amalgamated with Ross River. Lake Labarge Reserve No.1 was likewise amalgamated with Whitehorse Reserve No. 8 and the communities of Snag and Stewart River were joined to form the White River Band in the community of Beaver Creek.

Gilson and Smith said members were not consulted about the amalgamation. Documents also fail to show any indication that the Pelly Lakes band was formally informed of the decision.

Smith feels the DIA neglected their fiduciary trust by acting on the bands’ behalf without properly consulting them. The government likewise asserts they never surrendered their rights and title to their land.

“They did us wrong,” Smith said.

Like many in the community, Smith’s family was forced to relocate in the 1950s so he and his family could be closer residential school. They eventually settled near the Kaska community of Upper Liard near Watson Lake.

Despite this, Smith’s grandparents moved back to Pelly Banks in 1968. Smith would return to the area from 1969 to 1973 to go trapping. Today, his family’s cabins still stand.

Now, he wants his former band to be formally recognized by the federal government.

“It’s up to (the federal government) to correct what they did to us and our people.”

‘That’s where our land is’

Gilson said as a result of the amalgamation the Pelly Banks people are now scattered.

Today, a few dozen families remain in Pelly banks or have cabins in the area.

Former members and descendants are now mostly members of either RRDC or LFN in Watson Lake or other communities. A document provided to APTN News states Pelly Banks leaders estimate there are more than 200 descendants residing in Yukon communities.

Gilson said she knows of descendants living as far away as the N.W.T. and B.C.

Since the early 90s leaders like Smith have been formally working to have the band reinstated by the federal government.

In an effort to prove their existence, Pelly Banks leaders have searched various archival databases to compile records, including visiting the federal archive centre in Ottawa.

Documents shared with APTN showcase several letters sent to federal officials in hopes of raising awareness about their situation and receiving assistance to be reinstated.

Smith noted his people have ancestral responsibilities to the land and want to have their voice heard in matters that affect them.

“(We want to let the government know) we are there, we were there, and we want to be heard and be able to say (what we want to) as opposed to somebody talking for us,” he said.

“We want to see if we’d be able to go back there and people would be able to come back and live there, because that’s where our land is, that’s where we grew up for as long as we can remember.”

‘(We) need so much help.’

As an unrecognized First Nations government, Pelly Banks does not receive federal money, severely limiting what it can do.

Gilson and others working on behalf of the government don’t collect a paycheck, nor can they offer things like services and supports to members. Any functions or events held by the government are paid for out of pocket.

Gilson and Smith said federal cash and recognition could help advance their government’s interests.

“Pelly Banks needs so much help,” Gilson said.

Smith said these issues have caused Pelly Banks’ reinstatement to be a sensitive issue for some.

Hammond Dick, a Pelly Banks member, said their descendants have belonged to established bands for decades. He noted there is some apprehension surrounding the government and their cause.

“It’s a touchy subject because some of the members haven’t decided one way or the other to say that they are members of Pelly Banks,” he said.

LFN Chief Stephen Charlie likewise told APTN if Pelly Banks was reinstated it would impact his First Nation’s funding and services.

Under section 17 of the Indian Act, if a new band is created from an existing band, “reserve lands and funds of the existing band as the Minister determines shall be held for the use and benefit of the new band.”

But Smith said the Pelly Banks people want to be reinstated in a way that won’t affect other Kaska communities, and there is support in their efforts.

While RRDC declined to comment, Pelly Banks representatives provided documents showcasing RRDC’s and the Kaska Nation’s support of Pelly Banks’ reinstatement throughout the 90s and as recently as 2019.

Documents show at least five resolutions in support of reinstating Pelly Banks were passed by RRDC between 1993 and 2019.

In 2002 and 2019 former RRDC chief Jack Caesar wrote to federal ministers informing them of RRDC’s continued support.

A 1991 Kaska Nation assembly resolution likewise called for Pelly Banks to be recognized as a separate Kaska entity. That same year, George Miller, the former chief of what is now LFN, also wrote a letter in support of reinstating Pelly Banks.

“I want the Government/s to make this wrong a right fortwith,” he wrote.

Miller, who is now the vice-chair of research and reconciliation and interim chair for the Kaska Dena Council, said the Pelly Banks people are a distinct group who deserve to be reinstated.

“I personally support them and continue to support them until they’re a band,” he said.

KZK Mine

Gilson noted recognition could also help the Pelly Banks people in their efforts to have a say in a proposed mining project.

The Pelly Banks government says the Kudz Ze Kayah project, a proposed open-pit mineral mine by BMC Minerals, would be constructed on Kaska territory in an area sacred to the Pelly Banks people.

Gilson said the project’s site raises many environmental concerns for the Pelly Banks people, especially the effect its construction and operation could have on an important calving ground for the Finlayson caribou herd.

Members are also concerned the mine’s location is situated on the Atlantic-Pacific continental divide that are the headwaters for the Pelly and Liard rivers, an area beaming with traditional ties for the Pelly Banks people.

The Pelly Banks government shared its views on the project during a public review in 2021 to the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB), though BMC officials have disputed many of their concerns.

While Gilson said BMC has made some efforts to recognize Pelly Banks’ apprehensions, its people have largely been excluded from governmental discussions and decisions.

“Pelly Banks has never been brought to the table. Yet, it’s on our doorstep,” she said.

Last summer, a federal and territorial decision document identified four Kaska First Nations that would be impacted by the project.

The decision document states the federal Crown and territorial government have a legal duty to consult “with Indigenous groups whose asserted or established section 35 Aboriginal rights, or treaty rights, have the potential to be adversely impacted by a decision under YESAA (Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Act).”

The documents lists four Kaska First Nation whose rights and territory may be adversely impacted by the project, including RRDC and LFN.

Pelly Banks is briefly mentioned in the document, though not as a recognized First Nation.

Gilson said Pelly Bank’s inability to be meaningfully involved is a major point of frustration.

“Canada wants to treat us like we’re an interest group,” she said. “We’re the closest to where that mine is going to go in. We have a home 10 kilometers from where they’re proposing that mine.”

RRDC has likewise called the project into question.

Last year it filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Kaska Nation against the territorial and federal governments. The suit claims the governments advanced the project without properly consulting the impacted First Nations and calls for a judicial review.

The suit was heard in the Yukon Supreme Court in April and a decision is expected to be released later this summer.

Gilson said Pelly Banks has provided statements in support of the Kaska, but notes they could pursue their own legal action or join the case as intervenor if they had proper funding.

“Regardless if the federal government wants to acknowledge us we continue to raise our voice,” she said.

Section 17

Another point of frustration for the Pelly Banks people is that other amalgamated bands have since gone on to form their own First Nations.

That includes what is now the White River First Nation (WRFN) in the community of Beaver Creek, which was one of the bands amalgamated the same year as Pelly Banks.

In 1961, WRFN was amalgamated with the Burwash Band in Burwash Landing, forming what was then known as the Kluane Band. In 1990, the band split its Beaver Creek membership into the White River First Nation, and its Burwash membership became the Kluane First Nation.

Lake Labarge Reserve No.1, which was likewise amalgamated with Whitehorse Indian Band in 1956, went on to re-establish itself as the Ta’an Kwäch’än Council in 1987. It was formally recognized as a distinct First Nation by the DIA in 1998 and is now self-governing.

Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) spokesperson Jennifer Cooper said the department was unable to comment on Pelly Banks, though she confirmed officials have met with representatives of the Pelly Banks people and discussions are ongoing.

Smith said those discussions are centered around section 17 of the Indian Act, which deals with band division. For now, the section is the only option for Pelly Banks’ reinstatement.

However, Smith said section 17 has stipulations his people don’t agree with.

For example, only “new” bands can be created under section 17.

“We keep saying to the government we’re not a new band, we’re a band all along with our leaders in tact,” Smith said.

Under section 17 RRDC and LFN would also have to divide its assets with Pelly Banks if the government was reinstated. But Smith said his government doesn’t want to take resources away from other Kaska communities.

He noted there’s also the issue of Pelly Banks falling back under the Indian Act, something his people aren’t interested in as they would be governed under what he said is colonial legislation.

“For us, our people say you can’t live that way under the act, we want to have our own traditional ways through the governments,” he said.

Smith said Pelly Banks had its own traditional government system, including its own chiefs that would manage the land with input from elders and youth.

That system is not subject to current day laws and governance systems – something his people want to return to.

But with section 17 being their only recourse for now, Smith said Pelly Banks is stuck in a legal loophole.

“We’re still trying to pursue that but in a way of traditional government rather than the Indian Act, but they’re always pushing that section 17 on us,” he said.

Slowey said section 17 appears to put the onus back on the amalgamated band to do the work of reinstatement.

“(It’s putting) the burden on the communities to prove themselves, which is really, again, very colonial and paternalistic, but that’s the game on the table right now, unfortunately,” she said.

“(It’s) sort of like, ‘Okay, we created the problem, you guys figure it out.’”

Slowey noted there are other obstacles, too.

“The federal government’s been very clear about no new monies, whether it’s for new treaties, new negotiations or anything,” she said.

She added the federal government doesn’t provide many resources or staff to files like Pelly Banks, and with added changeover and bureaucracy, it will likely be a lengthy, uphill battle for reinstatement.

“The federal government’s not coming to you to settle a claim, so you have to keep at it,” she said.

“I have no idea what is involved or what entails, but just by observing the treaty making process itself, it’s a very slow process.”

While it’s unclear what the future may hold for Pelly Banks people, its members continue to hold out hope that they may one day be reinstated.

Under section 17, a band can be created from a majority vote.

In 2019, Pelly Banks leaders called on then Crown-Indigenous Relations minister Carolyn Bennett to help them hold a referendum for the Kaska Nation to vote on a legal separation.

While that has yet to happen, Smith is hopeful a referendum could help Pelly Banks advance their efforts.

According to ISC’s website, “if asked and under exceptional unusual circumstances, the Governor in Council can create a new band from a formerly unrecognized group of persons.”

This was the case with Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation in Newfoundland and Labrador.

“When Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949, Mi’kmaq communities were not recognized as First Nations under the Indian Act and their legal status, as well as the status of their members, was uncertain,” the ISC website states.

“Discussions between the Government of Canada and the Federation of Newfoundland Indians (FNI) led, in 2008, to the Agreement for the Recognition of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq Band.”

Qalipu was established as a band under the Indian Act in 2011 by an Order in Council.

The band has no reserve land but is composed of 67 traditional Mi’kmaq communities, spread across the island of Newfoundland.

In 2020, Justice Michael L. Phelan ruled the Chacachas Band and the Kakisiwew Band were illegally amalgamated under the Indian Act in 1884 to form the Ochapowace First Nation, located roughly 150 km east of Regina, Sask.

“The Federal Court determined that the amalgamation of two Treaty 4 Indian Bands, the Chacachas and Kakisiwew into the Ochapowace Indian Band, was unlawful by virtue of the failure of the federal Crown to implement the promises of Treaty 4 in accordance with its obligation of “honour of the Crown,’” court documents state.

Both bands claimed that lands surveyed in 1876 became reserves lands for each band separately.

“In 1881 Canada surveyed a joint reserve for the Kakisiwew and Chacachas and in 1884 the two bands were combined without consent into one band when Chief Ochapowace became chief of the amalgamated band: the Ochapowace Band,” the documents state.

Like Pelly Banks, descendants of both bands claimed the amalgamation was done without their required consent and claimed it was a breach of the federal government’s fiduciary duties.

While Canada denied the bands claims and asserted the amalgamation was done with consent, a Federal court found otherwise in 2008. It said the “Chacachas Band has continued as a distinct rights bearing collective even if not recognized as a band under the Indian Act, and it is entitled to assert treaty rights under Treaty 4.”

The Chacachas and Kakisiwew Bands are unable to pursue further treaty land entitlements because of settlement agreements made with Canada. A second phase of litigation will address separation and other complex issues.

As neither bands appealed the decision, it stands as applicable law. The bands are now engaged in negotiations to avoid returning to Federal Court.

Gilson said she’s also seen a positive step towards reinstatement.

Last year, the government received a small amount of money from the federal government to hire a researcher to help them produce a historical record documentation project.

The documents produced will be used to help Pelly Banks assert its claims.

“It’s a big step, and it’s a step that was missing for 73 years,” Gilson said.

Slowey said while it’s a positive that Canada is providing resources for groups like Pelly Banks, it’s unfortunate they have to prove their existence.

“That’s part of the process, setting up that sort of anthropological verification for the federal government to therefore say, ‘Okay, yes, you’ve been here.’”

While Smith isn’t sure if Pelly Banks will be reinstated in his lifetime, he’s hopeful there will one day be a settlement for his people.

“There’s just cabins there now, but maybe in the future there could be an opportunity to develop a small community there,” he said.

Gilson said as the federal government continues to make efforts to recognize its part in residential schools, the destruction of languages and missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, she’s hopeful Pelly Banks will one day be reinstated.

Until then, she wants the world to know that Pelly Banks still exists.

“We’re still alive. We’re still on our land before any government came here and told us whether we have the right to exist or not. Who are they to tell us that we have the right to exist or not?”

Three-part series

Over seventy years ago, the federal government dismantled a Kaska Nation band in the Yukon, forcibly amalgamating its members with another band.

Now former members and descendants are coming forward, claiming that they were wrongfully and illegally amalgamated and seeking reinstatement.

Reporter Sara Connors delves into their history and introduces us to some of the individuals who are fighting for justice and recognition.