Inside Corrections

APTN Investigates is taking viewers inside corrections facilities to see what’s really behind the overrepresentation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada’s justice system.

While Indigenous Peoples make up just under five per cent of the Canadian population, they now account for more than 32% of all incarcerated inmates.

In this special four-part series, the APTN Investigates team brings viewers with them behind the walls of some of Canada’s most notorious prisons. Inside Corrections looks to understand why Indigenous Peoples are the fastest-growing prison population in the country.

The following story contains footage and discussion of violence and self-harm that may be distressing.

Talk Suicide Canada is available by phone at 1-833-456-4566 or by text message at 45645.

Footage obtained through access to information requests reveals the Correctional Service of Canada’s (CSC) response to prisoners in mental health crises.

Federal inmate Joey Toutsaint has spent 2180 days in solitary confinement and is the primary subject of the footage.

The CCTV footage was taken by CSC staff after a use of force incident or after Toutsaint exhibited self-harming behaviour.

The footage, while graphic, offers insight into how the CSC responds to prisoners who are experiencing mental health challenges as a result of prolonged isolation.

APTN Investigates was given special access to the Millhaven Institution, where Toutsaint was held in custody at the time of the interview.

He says his experience in federal custody is something no person should ever have to endure.

Toutsaint entered the prison system at the age of 15, spending most of his life in custody. He is now 36 years old.

“Just locked up all day, you go through a lot, a lot, a lot of mental breakdowns, suicidal thoughts and self-harming,” he said, from inside the maximum-security facility.

Indigenous inmates continue to be overrepresented at all levels of Canada’s correctional system.

Isolation, self-harm and suicide are all more likely to occur with Indigenous inmates, according to a report released by the Correctional Investigator of Canada, Ivan Zinger.

“I think we concluded that very much so, that there are systemic barriers and biases and systemic racism in federal corrections that is very much embedded in practices and policies,” said Zinger.

The impact has a detrimental impact on each Indigenous person who is serving a federal sentence, he added.

In 2018, the federal government introduced Bill C-83, an amendment to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act.

The legislation was introduced after the Supreme Court of Canada found that the use of solitary confinement violated the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Additionally, it found that isolating inmates for more than 15 days would constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

After administrative segregation was banned, a new form of isolation was introduced. It’s now referred to as a structured intervention unit (SIU).

Jennifer Metcalfe is the executive director of the Prisoner’s Legal Services and represented Toutsaint in a human rights complaint.

She says the main difference between administrative segregation and a structured intervention unit is the additional two hours a prisoner receives outside of their cell.

“The new regime that replaced it requires CSC to offer at least four hours out of a prison cell each day and two of those four hours are supposed to include meaningful human contact,” she said.

Joey Toutsaint says the introduction of the new legislation has yet to make a positive impact on him.

“I’m really struggling, I just don’t know what to do sometimes,” he said. “I don’t even know why I’m trying sometimes, but I’m trying hard to get the help that I need.”

Senator Kim Pate has advocated for prisoner’s rights for decades and she says the legislation is in immediate need of oversight.

“In fewer than five percent of all of the placements in the structured intervention units was the law followed consistently,” she said.

Pate says the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in Canada’s correctional system is a continuation of removing Indigenous people from their communities.

“Does it surprise me he’s there? No. Is it atrocious? Is it inappropriate? Is it unlawful? Should it be revisited? Yes,” said Pate.

Last month, Toutsaint was transferred to Saskatchewan Penitentiary.

In 2009, Toutsaint was labelled a dangerous offender and given an indeterminate sentence.

There’s no telling when, or if he will ever get out.

“No matter how much I try, they don’t want to give me a chance now,” he said. “They’re just always looking for an excuse to keep me in jail.”

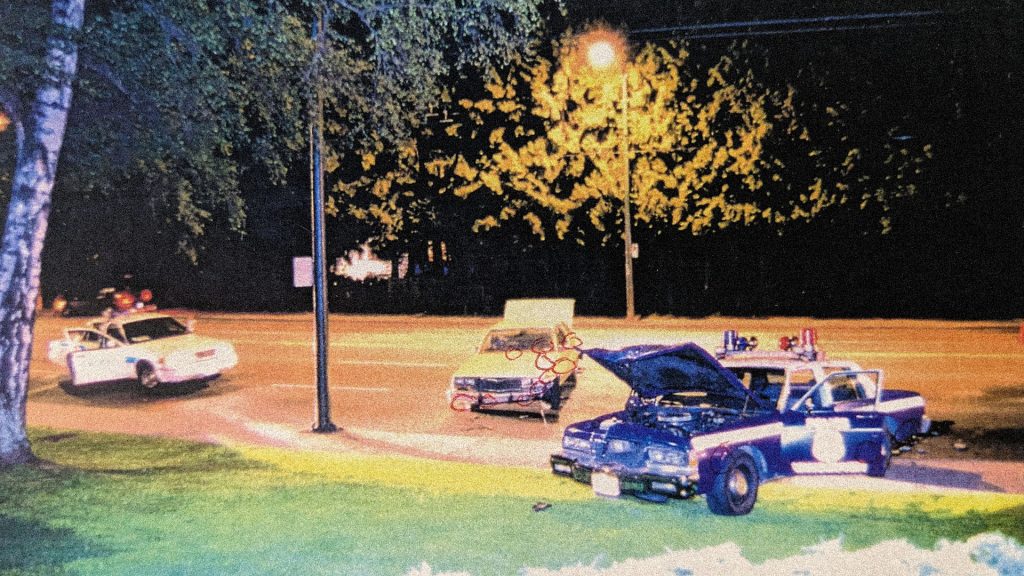

To hear John Derek Mills tell it, the Vancouver police went rogue. At his trial he called them “crazed cowboys.” He says they were shooting indiscriminately into a getaway car and that put his companion and her two children in danger.

For Mills this was the inciting incident.

Protect the child. It’s all he recalls thinking when he scooped up a two-and-half-year-old child. He bolted from his car, jumped into an empty police cruiser and proceeded to take VPD on what was termed then the longest and most violent police chase in Vancouver history.

For over 30 blocks, with a child in his lap, Mills sped through the city at a speed of up to 120 kilometres an hour.

For him it was self-defence. He was only protecting the child.

But the trial judge wasn’t buying it, calling the evidence presented by the defence not reliable.

Several police officers testified that at various points of the chase Mills held the gun to the child’s head. Using the child as a shield as he attempted to flee.

According to one officer Mills yelled, “stop or I’ll shoot the kid.”

The judge found Mills guilty on multiple charges, including firing at police, taking the child hostage and threatening the child with his gun and causing bodily harm to the child due to criminal negligence.

At sentencing the last words from the judge labelled Mills “an extreme danger to the public” and gave him life, eligible for parole after seven years.

He was convicted March 13, 1998. Twenty-five years ago, this week.

Mills admits to his crimes. Except for one. He did not take the child hostage. He did not threaten her. In almost three decades Mills’ story has not changed. He maintains the cops’ reaction was excessive.

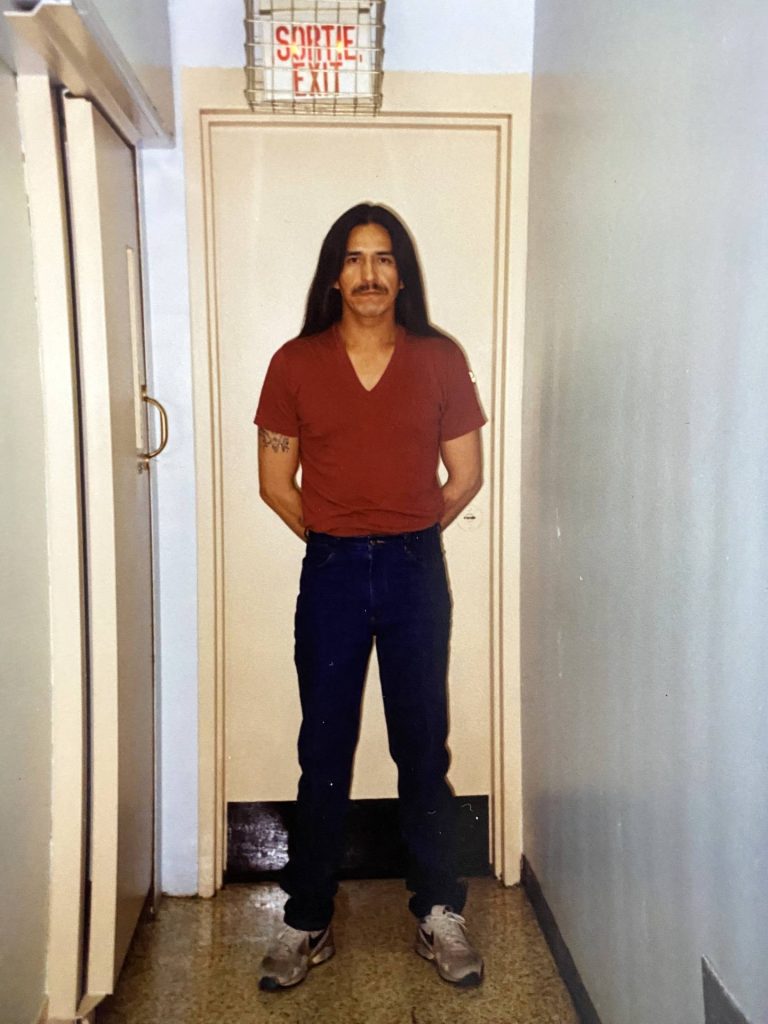

“What they said isn’t true. I can’t prove what they were thinking” Mills told APTN investigates in an interview conducted at Archambault prison in Quebec.

On June 5, 1996, Mills decided to knock of a drug store because he and his girlfriend were broke. Her children needed to eat.

“I felt so guilty that I wasn’t able to provide for them. The girls were so good like you didn’t hear a peep out of them the whole time. I found some change that I dropped. I got them some chips and some juice. Sheena, she just grabbed them like she was ravenously hungry and then that really kicked into high gear. If you have a choice between a robbery and a starving kid, what would you choose?”

Mills and his girlfriend had just arrived in Vancouver from Edmonton. They spent the day applying for social assistance. But were denied. But at the time in B.C., you had to be a resident for at least six months before you were eligible.

His girlfriend was taken into custody the night of the crime but did not serve any time.

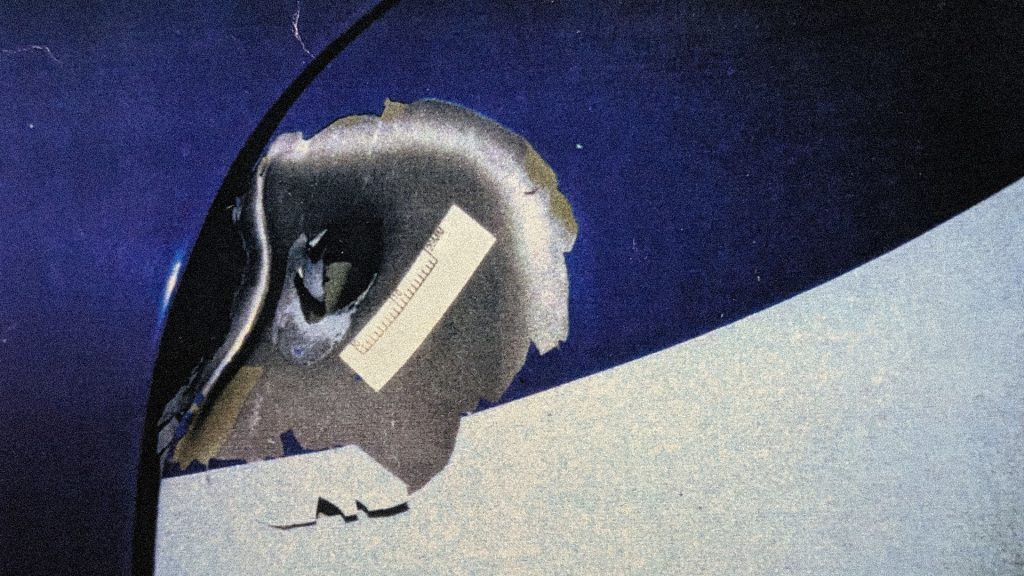

During the trial, police admitted to destroying the getaway car. A car Mills insists was riddled with bullets.

On cross-examination defence got one eyewitness to admit maybe the accused did not have the gun to the child’s head. He also testified that he had heard 14 gunshots in total.

This and other discrepancies have Mills hoping for a new trial. He is waiting for his ex-girlfriend to come forward to back up his version of events. He claims a witness came forward to a local paper and informed them he had seen the car before it was crushed, and he did see bullet holes.

He knows he’s dead in the water without new evidence. He has a parole hearing next month but without admitting to all his crimes the chances of him getting out are almost zero. Mills conceded he will be in jail for a very long time

“I never killed him.”

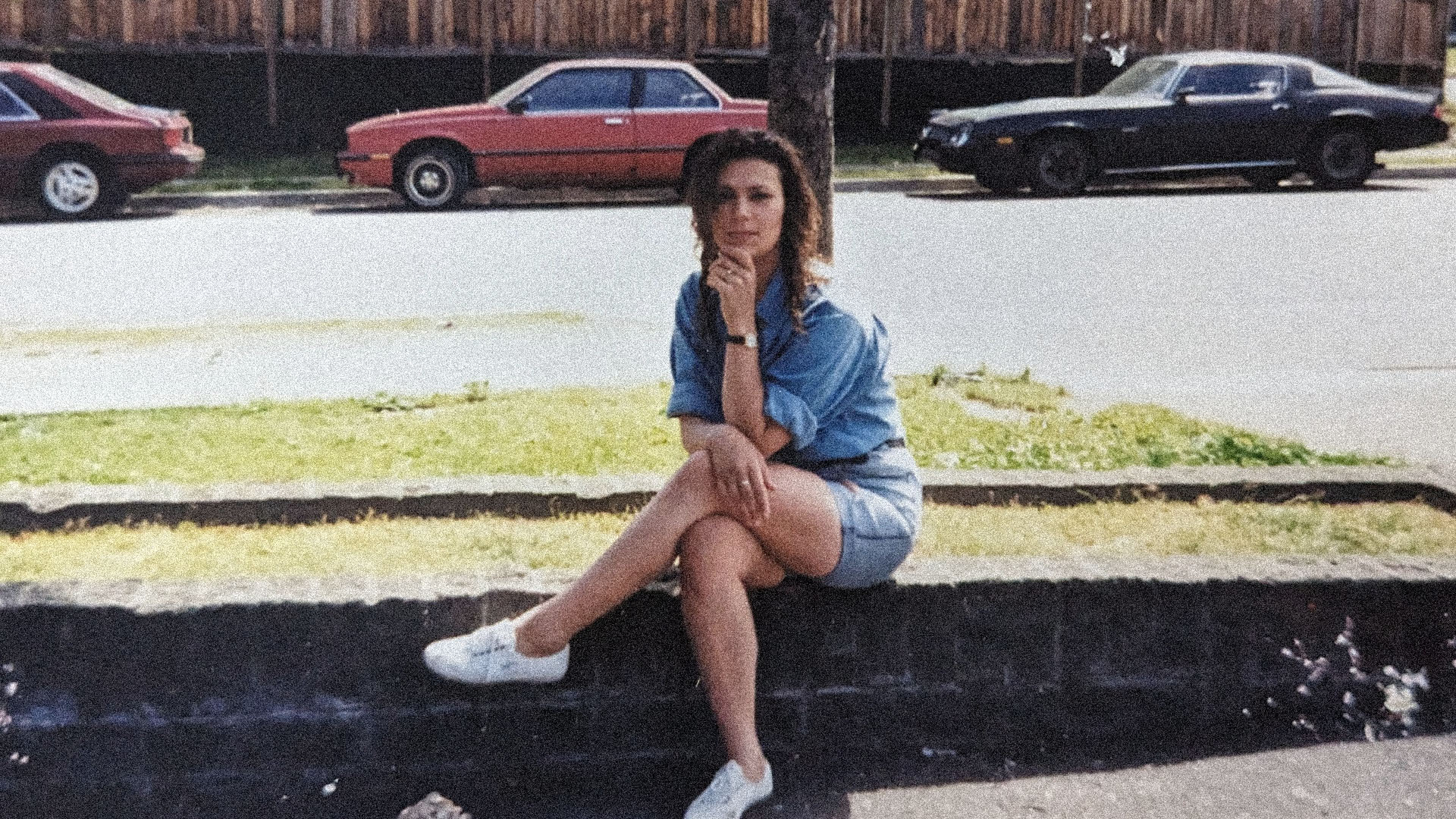

Odelia Quewezance

Odelia Quewezance insists she did not kill Anthony Joseph Dolff.

The 70-year-old farmer was murdered in 1993 in his home in Kamsack, Saskatchewan. He was stabbed 17 times, hit on the head with a television, and strangled with a telephone cord.

Soon after, Odelia and her younger sister Nerissa were taken into custody, accused of the crime.

“I honestly believe that I should have never been charged with second degree,” Odelia Quewezance said.

According to court documents, Odelia, then 21, Nerissa, 19, and their cousin Jason Keshane, 14, were drinking with Dolff at his farm house on the night he was killed.

“He was making sexual advances toward me,” Quewezance recalls. “I remember we were drinking. I went in the room with him. And he wanted to pay me, give me money to have sex with him.”

Things turned violent after an envelope with $700 in cash went missing. Odelia says Dolff started making sexual advances towards both young women.

APTN Investigates has been following this story for years now.

“I kind of got mad that because I’ve been protecting my sisters all my life. And I think I finally just you know, I told him leave my sister alone, don’t bother with her. And then that’s when this all broke out and this stuff happened,” Odelia said in 2020.

Both women entered pleas of not guilty, but both were ultimately convicted and sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 10 years.

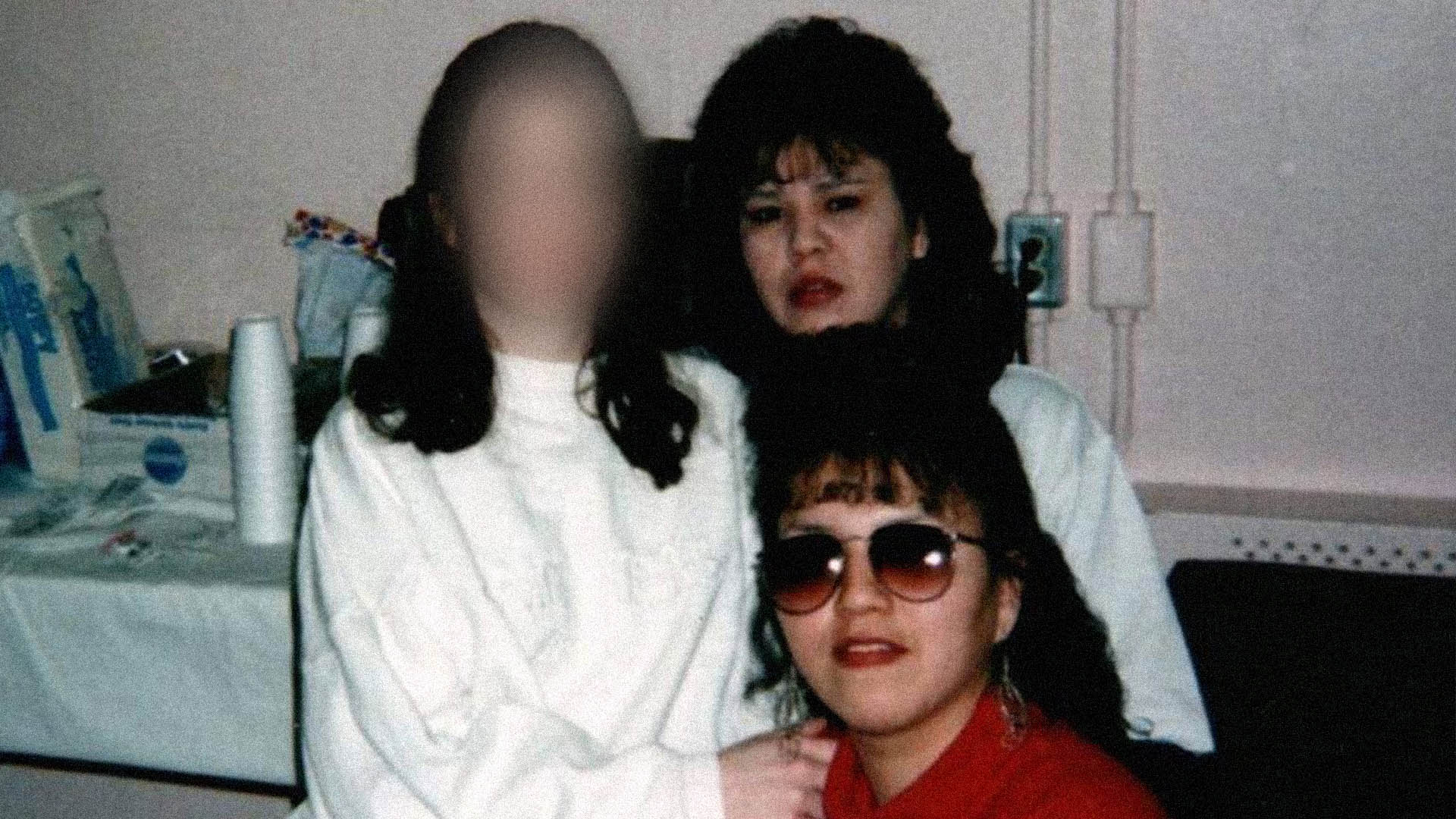

After our initial story, several high-profile people came to the sisters’ aid.

“We need to expose the ways in which we have created an environment that every system failed them. And the only system that could not refuse them was the prison system,” said Senator Kim Pate.

“We want Canadians to know, really what the justice system in Canada is about, and how it’s unfairly applied to Indigenous people and Indigenous women,” said Congress of Aboriginal Peoples national Vice-Chief, Kim Beaudin.

David Milgaard advocated for the sisters before his death in May of 2022, working with the Innocence Project to free them. He is the victim of one of Canada’s most infamous wrongful convictions. Before being released, he served 23 years for a rape and murder that he didn’t commit.

We first covered their story in 2020. That’s when their cousin confessed on air to our reporter John Murray. Jason Keshane was charged with second degree murder, convicted as a youth and sentenced to five years.

Milgaard’s death hit the sisters hard.

“When I heard the news, it was like losing my brother, how I felt when I lost my brothers. I got a message, the last message, he messaged me and he said, he always has that free Nerissa, free Odelia, you know? He sent me that and I said I’m going home this weekend and his last words were, I’m so happy for you. Have a good visit with your family and he says, you need to go home,” Odelia said.

Odelia is now on day parole. Nerissa is currently incarcerated at the Fraser Valley Institution for Women in British Columbia.

Both women have been released at various times throughout the years, but have ended up back in prison for violating their conditions.

James Lockyer is a criminal defense lawyer and the founder of Innocence Canada.

He says the court documents show the sisters were held and interrogated at the Kamsack RCMP detachment without the presence of a lawyer.

Lockyer has taken on the Quewezance sister’s case pro bono. He met them through David Milgaard, who Lockyer also represented.

In June 2022, Canada’s Justice Minister David Lametti admitted that there may have been a miscarriage of justice in the sisters’ case.

“I’m asking to be free today. I’m asking to be free, because I know in my heart, I did not kill Mr. Dolff. I’m sorry that happened. I’m just asking, my sister is still suffering in prison and she doesn’t deserve that. And I don’t deserve it,” Odelia said at a press conference at the time.

“If they’d been white, would they have been arrested in the first place for the murder? Probably not. If they were white and they’d been arrested for the murder, would they have been convicted of it? No.”

“And if they were white and they’d been convicted of the murder, would they now be out on parole? Absolutely for sure they would. Of course, they would. And that helps us understand how the justice system treats the Indigenous,” said Lockyer.

Lockyer says it’s now up to Lametti to quash the convictions or order a new trial by finding evidence the women had been wrongfully convicted.

Odelia and Nerissa have applied to be release on conditions while their case is reviewed by federal prosecutors as a possible miscarriage of justice.

The bail hearing is in Yorkton, Sask., the same courthouse they were convicted of second-degree murder in 1994.

“I’m feeling a little nervous and emotional, but I’m ready today.” Odelia said before the hearing.

The sisters were reunited briefly outside the courthouse. It’s their first time seeing each other in 18 years.

But the bail hearing was pushed to the new year.

The sisters are now two of Canada’s longest serving inmates.

“I was talking to my oldest daughter, Hayley, and she was mentioning, she was like, ‘Wow mom, you’re 51 today and you were in prison for 30 years and four to five years in a boarding school.’ So, I’ve been confined most of my life,” Odelia said in January.

Their story has become a symbol for the injustices Indigenous women face in Canada’s legal system.

“What the judge has to look at is, will releasing these two women on bail, pending the review of their wrongful convictions, result in a risk to public safety? And I think the very clear answer is no,” said Senator Pate.

“Nerissa calls me once in a while. She’s waiting, like you know, as much anxiety as I get. But she’s staying strong, like we always tell each other, be strong and not to give up. But I told her just don’t lose faith,” added Odelia.

Indigenous women make up the fastest growing prison population in the country. They now account for more than 50 percent of all federally sentenced women.

“When they first came into the system, they like so many, particularly young people and especially young Indigenous women, took responsibility for what they were part of. They thought that because they were even there, they were just as responsible as their cousin. I didn’t know until years later that their cousin had actually confessed to being the one to actually do the killing,” said Pate.

Pate is one of three Canadian senators calling for the exoneration of 12 Indigenous women-including the Quewezance sisters. The senators are calling for their cases to be reviewed for possible miscarriages of justice.

“The reason we did the report is these are all women who either pled guilty or were found guilty. Virtually no defense was put up for them. In some cases, evidence became clearer later on. But in many cases, the information was there all along, but was either ignored or not seen as relevant or was not believed,” said Pate.

For now, it appears as though the federal government is open to addressing mounting concerns surrounding wrongful convictions.

“As minister, I’ve seen the process up close. When I look at the files that come to me, I see a clear pattern. The applicants are overwhelmingly white men, and our prison populations do not look like that. This tells me that the system is not as accessible to women or to Indigenous peoples or Black or racialized people who are disproportionately represented in our criminal justice system. We have to change that,” federal Justice Minister David Lametti said during a February 2023 press conference.

Lametti recently introduced new legislation in the House of Commons. Bill C-40 or David and Joyce Milgaard’s Law. If enacted, the bill could make it easier for people who may have been wrongfully convicted to have their cases reviewed.

“Today is the best possible news for the wrongly convicted in Canada. Finally, we have a tribunal that is independent of government, independent of the department of justice, that is going to review claims of wrongful conviction. Something that we have been advocating for, for those 30 years,” Lockyer said in response to Lametti’s remarks.

For now, both Odelia and Nerissa have no choice but to keep waiting. On Feb. 23 the judge delayed his bail decision again, setting another court date for March 27.

I don’t think the month delay is a real issue. He’s said that he is willing to bring it forward if he makes his decision sooner and I know that he will be diligently working on it. Like today he’s very up on the new legislation, he’s up on the case law. I have every confidence that he’s going to give a really thoughtful and reasoned decision. And I’m hopeful that it will go our way,” said the sisters’ lawyer Deanna Harris.

The decision could now come at any time. For the sisters, it can’t come soon enough.

“I just pray today, that tomorrow is a good outcome. But you know what? I’m not going to sit here and say, what’s another day?

I’ve waiting 31 years, right? That’s not fair. I shouldn’t even have to wait another day. Me or my sister,” said Odelia.

With files from private investigator Jolene Johnson.

On one side:

A supermax prison criticized for its treatment of inmates. On the other, an Indigenous healing centre with empty beds.

Daryle Kent opens the door to his deep red Nissian Altima and gets in.

“We’re gonna go downtown Ottawa, it’s a route I normally travel,” Kent explains as he creeps towards an intersection. “There’s a lot of activity down there, people down there, and I like to see what’s going on.”

The Ojibway man takes pride in his car. He better… he’s currently working overnight weekend shifts to pay for it.

But Kent, 60, says it’s worth the freedom it brings.

“Driving, it reminds me of when I was in the pen I used to see movies, TV shows, and I’d think about the times I would’ve liked to have been out there. Just being in the city, everything is new to me,” he said.

Before Kent can finish his thought, his phone rings.

“Uh oh, it’s my P.O. [parole officer],” he says.

The parole officer says that because of a parole violation, he needs to go under house arrest.

The violation?

Driving beyond his allowed 100 km radius to visit a friend who wasn’t preapproved by the parole officer.

Last year Kent was released after 38 years in prison.

While at Stony Mountain penitentiary in 1984, he was one of the masterminds behind a riot that claimed two lives.

He was 21 years old.

“I recruited a couple of guys to help me, just to start a riot, take hostages,” Kent explains while he drives. “There was a miscommunication, one of the guys whose first language was Cree didn’t understand what hostage meant, he thought it meant kill.

“When the scuffle started, he started stabbing.”

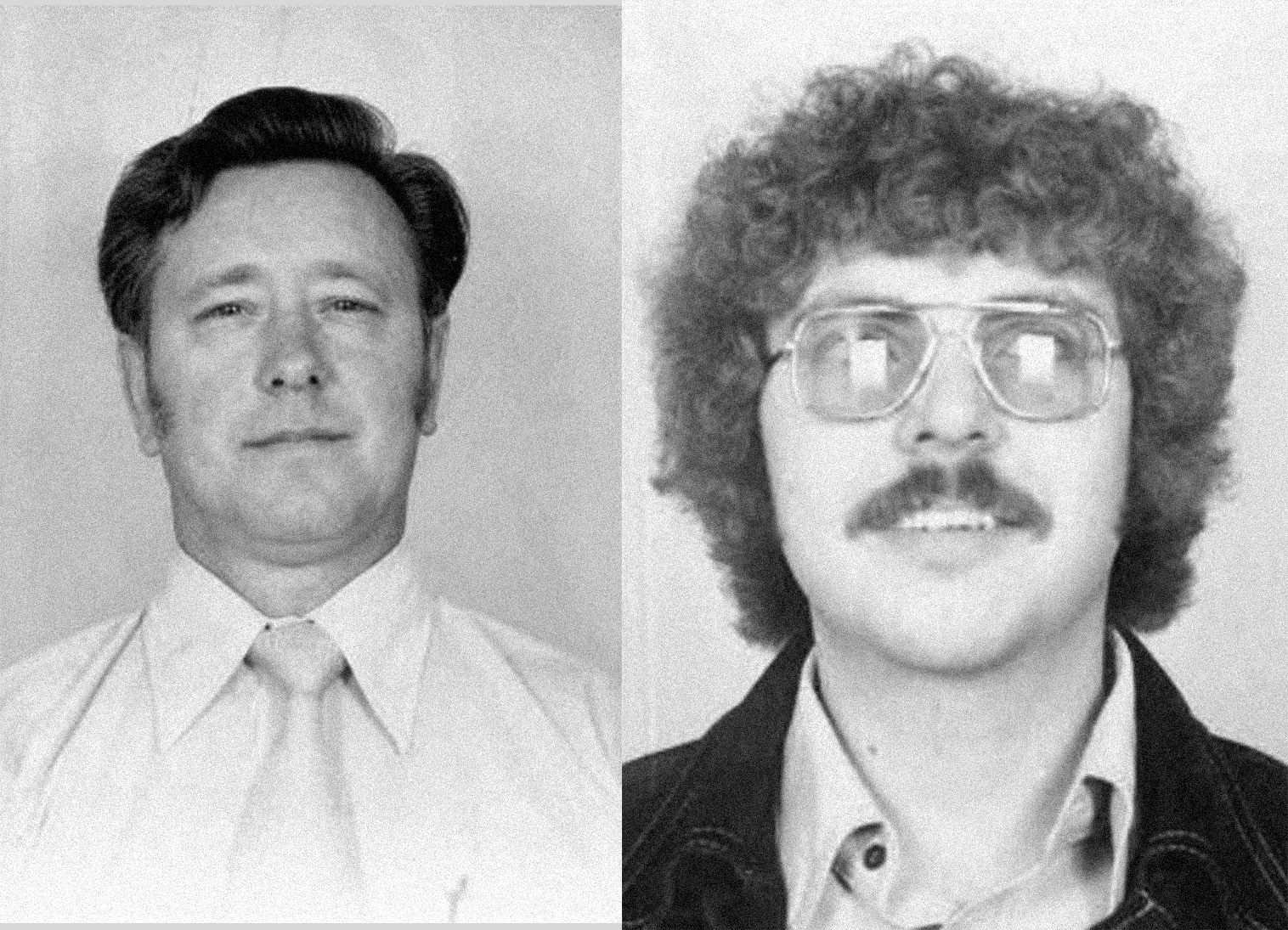

Two correctional officers, Joseph Wendl and Werner Friesen were murdered.

It’s one of the deadliest days in the history of Canadian corrections.

“I know those two guys were good people,” Kent says of Wendl and Friesen. “They treated everybody with respect. It’s just that they were there,” he adds with resignation.

Kent was convicted of first-degree murder and manslaughter for the role he played in their deaths.

Wendl, 54, left behind a wife and three children.

Friesen, 33, had a two-year-old daughter and wife who was six months pregnant.

“There’s nothing I can say. I understand their anger if they have that anger still with me,” Kent says of his victim’s families.

“The other part that struck me the most was Friesen’s daughter, the little girls. I know what it’s like to grow up without parents, so that hurt me,” says Kent, fighting back tears. “That was kind of what changed my life.”

When he was five years old, Kent lost both of his parents and an older sister in a car accident.

Raised by his grandparents, he says it was in school when the troubles began.

Originally from Brokenhead Ojibway Nation in southern Manitoba, he found himself subjected to racist taunts at the nearby mostly white elementary school.

“The school administrators, the principal, was siding with the people who instigate making racial comments or starting fights, they’d lose the fights a lot of the times and then we’d get the strap, Indian kids would get the strap,” Kent says.

From there, he describes carrying a rage that always simmered near the surface, waiting for provocation.

“Out of anger, frustration, I knew these other kids didn’t get the strap, so I went to basement of the school there, the white school, and tried to set it on fire,” Kent remembers. “There was a little fire started, the alarms went off, but it went out.”

After getting caught for the school fire, Kent went from one institution to another.

An abusive foster care home.

Youth detention.

A life of crime to feed his burgeoning substance abuse problem, which then lands him in provincial jail for robbery.

Then Stony Mountain.

“There was a lot of hostility there on the part of the staff and the inmates,” he says. “There were a lot of assaults, and then there was racial conflict between certain inmates, Caucasians and Indians.”

Kent has spent the last year living at a halfway house.

Judging from his parole record that he provided APTN, he’s adjusted well.

But the last thing he wants is to be seen as is a success story for the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC).

“Prison is a huge dysfunctional environment. Not just with prisoners, but staff as well,” he says.

Kent says not only was there a missed opportunity to help him as a young man before the events of 1984, but that most of the services that came after were poor.

“I just lived angerly in prison,” Kent explains. “The prison environment is too hostile for any kind of positive change. I think society has to look at, what does justice really mean?”

The statistics back up a lot of what Kent is saying.

According to CSC, 38 per cent of people entering the prison system are Indigenous offenders.

Indigenous Peoples make up five per cent of Canada’s population – but they make up 32 per cent of people in prison.

They are increasingly entering the system at a younger age where they do a higher proportion of their sentences than other offenders.

They serve their sentences at higher levels of security.

And then they are 65 per cent more likely than any other group to return after release.

“Why is it failing? It’s that we’ve been asking the wrong questions and looking at the wrong solutions,” says Dr. Vicki Chartrand, a criminologist and a professor at Bishop’s University southeast of Montreal.

For 25 years Chartrand has been visiting prisons and speaking to inmates.

“The majority of people going into prison aren’t having their basic needs met in terms of dealing with post traumatic stress, histories of violence, trauma, those basic needs aren’t being met, in fact in prison, it’s actually exasperating them,” says Chartrand.

The CSC does offer a variety of programs and services to Indigenous inmates. Talking circles, meetings with elders, changing of the season ceremonies are some examples of what’s available.

“Despite all these efforts, we haven’t reduced the Indigenous rates of incarceration, in fact while the general rates of incarceration have been going down for the last ten years, Indigenous incarceration rates have been going up,” says Chartrand.

“What I hear over and over again is that the prison system is the first place and often the only place where they receive any kind of Indigenous culture or training, and of course that’s been fused by a white European framework, a prison. So it’s a really sad statement for Canada that Indigenous people are experiencing their culture, traditions and spirituality for the first time in a punitive and brutalizing environment like prison.”

Chartrand says that part of the problem is that the resources aren’t in the communities.

Corrections Canada has a nearly $300 billion dollar budget and one of the highest staff to inmate ratios in the world.

“We need to move away from investing in the system,” says Chartrand.

Kent, who is about to head back to a halfway house, agrees.

“It’s all about money, that’s the sad part about it. Money, runs everything,” says Kent. “The act of rehabilitation doesn’t really occur in prison. You have to teach people how to live.”

As much as he’d prefer not to be, Kent is a good case study of the workings of the incarceral system in Canada.

If he is not an expert, than who is?

The Supermax

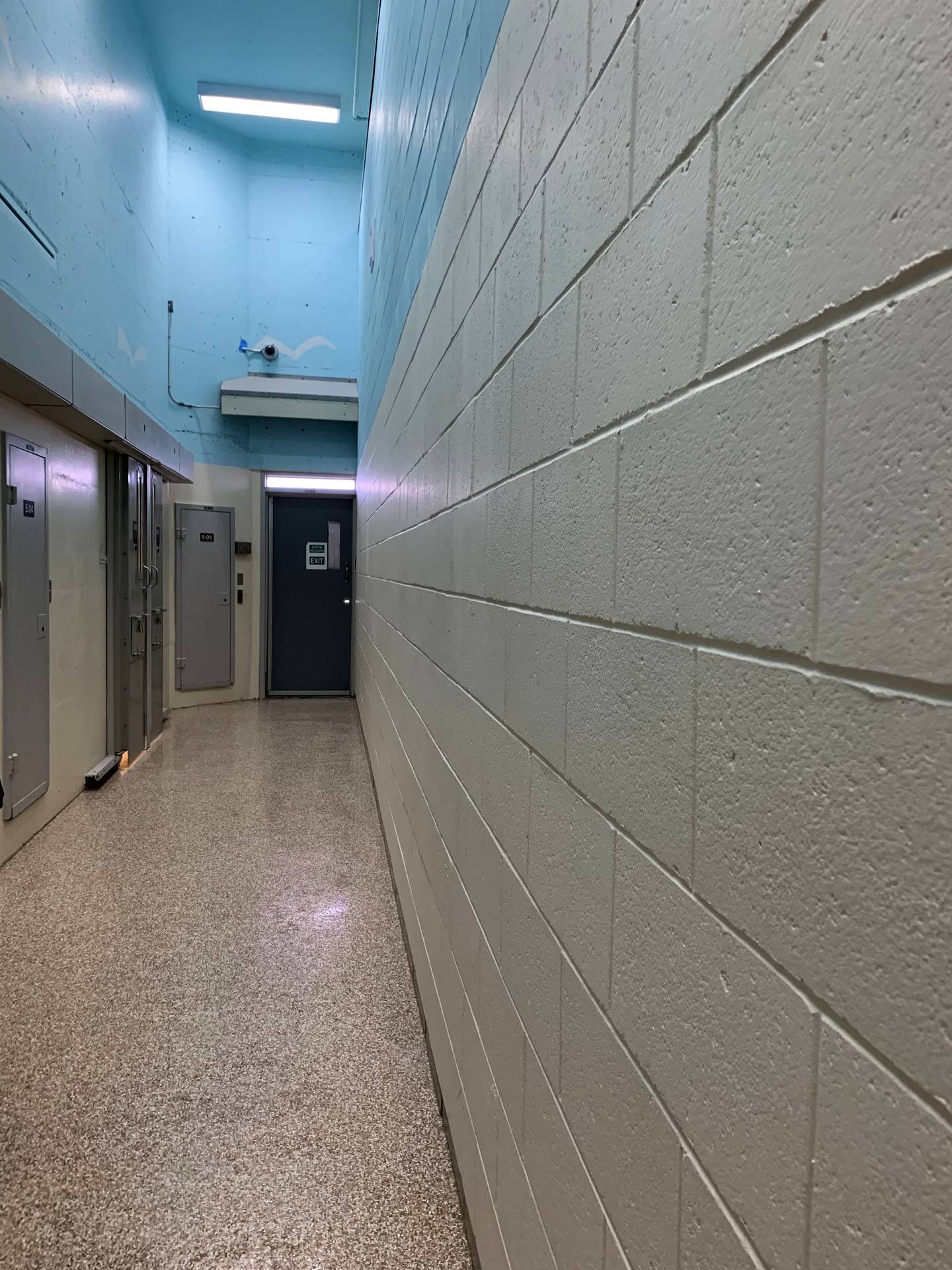

Following the riot and his murder and manslaughter convictions, Kent did a spell at the Special Handling Unit (SHU).

Despite its innocuous sounding name, people who have been in the SHU say it’s anything but.

“A prison for prisoners, you know? There’s nothing there,” Kent says.

Located about 50 km north of Montreal, the SHU is Canada’s only super maximum prison.

Situated within a larger complex called the regional reception centre, it’s a prison within a prison.

Judging from some more recent inmates, not much has changed.

“I wouldn’t wish it on anyone, it’s a very dangerous place,” says a former SHU inmate APTN has agreed to name David at the request of his lawyer.

“The worst of all, Hell,” adds another former inmate APTN is calling Tyler.

Tyler and David are part of a class action lawsuit against the federal government.

When asked to elaborate on their experiences there, they were quick to provide details, many of which overlap.

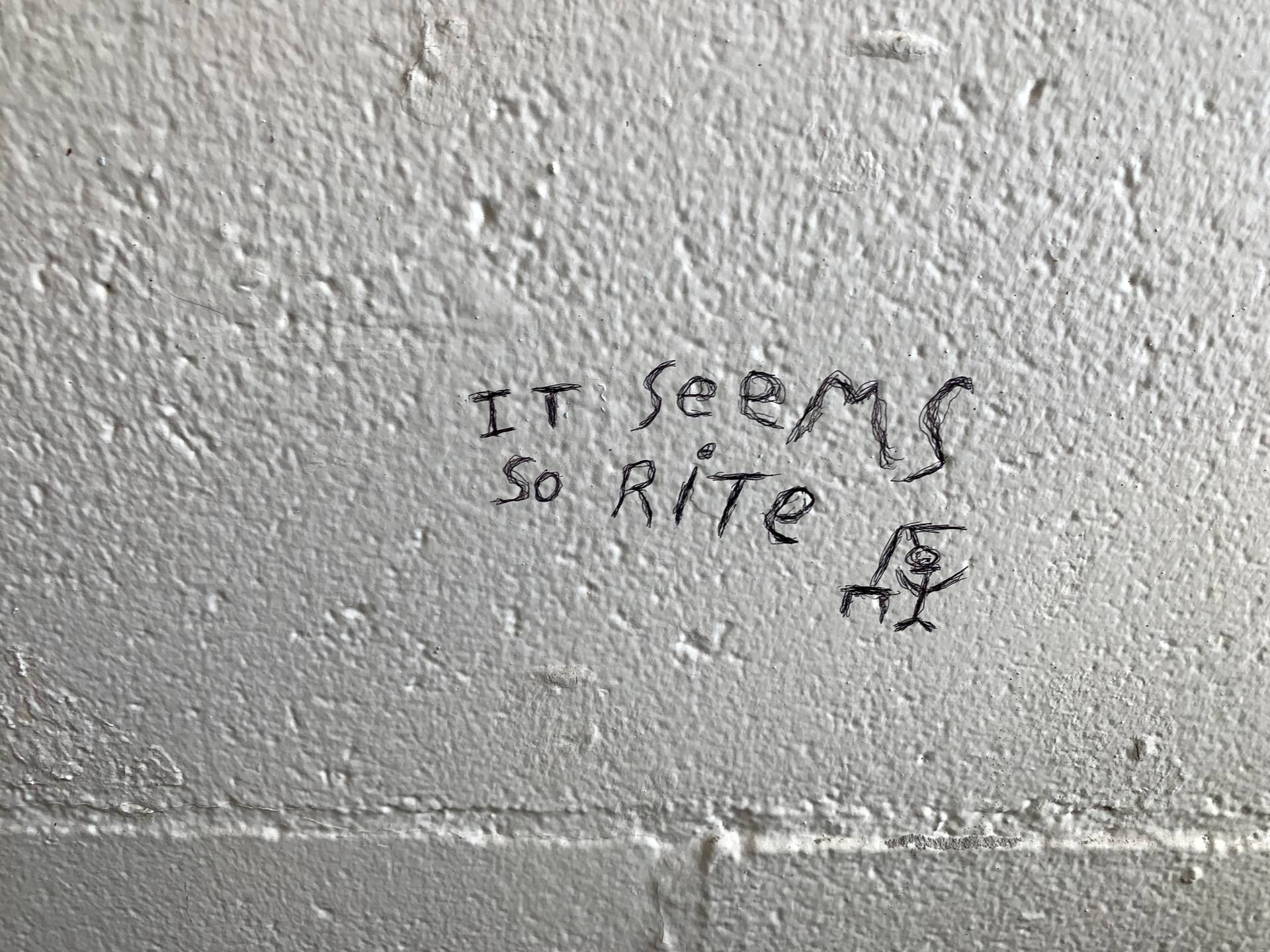

“I’ve been stabbed there, and I didn’t deserve it,” says David. “It’s like psychological abuse, because they try to break you down, slowly pick away at your mental capacity and just make you lose your mind.”

“We’re basically locked in our cells all day,” says Tyler. “Nothing but to sit there and think. No programming, just sit in your cell.”

These allegations have yet to be tested in court.

“We take the inmates that we’ve judged the most problematic, who have the most difficulties, we put them all together, we don’t offer them any social reintegration programs, no follow ups with intervention workers, with social workers, with conditional release officers, not really any psychological follow ups, and we lock them up the most we can in cells and then we wait for them to suddenly succeed in working on their problems,” says Marie-Claude Lacroix, one of the lawyers behind the class action.

Currently there are 117 plaintiffs, the majority of whom are Indigenous, says Lacroix.

They are each asking for $550,000 in damages, with an additional $800-$1000 per day spent in the SHU.

Some of the complaints they are bringing to court include spending at least 20 to 21 hours a day in a cell with little light from a small window, outside time is limited to the night when not summer, there’s no meaningful human contact, the common area is a confined, hostile space and there are few programs, especially for Indigenous inmates.

“Like smudging and stuff like this? Once in a while, you know you’ll have the elder come in and do a little session, but then again you’re behind a cage, so you’re an animal,” says David.

“The elder’s on the other side so you have bars between you, and there’s a little, like, cubby with plexiglass that he puts the shell through.

“It’s very degrading. You feel like you’re subhuman.”

Tyler says he would see an elder maybe once a month at the SHU, a stark contrast to what he’d get in other lower security lockups.

“We would have a native gathering or circle maybe once a week? Then we would have a change of season ceremony,” says Tyler of services offered at non SHU prisons. “But for the SHU it was nothing.”

Other former SHU inmates APTN spoke with told similar anecdotes of having ceremonies denied or just never happening at all.

The CSC declined our request to go inside the SHU.

But Senator Kim Pate has been there and she wasn’t impressed.

She says that because inmates spend long hours in SHU cells isolated from others, it’s akin to solitary confinement… something Canadian courts have recently made illegal.

“Many people with expertise in this area have said if you go into isolation and you don’t already have mental health issues, you will have mental health issues fairly quickly,” says Pate.

“The special handling unit violates the Mandela rules at every level. And remember the Mandela rules, the UN minimum standard rules on the treatment of prisoners, is a document that is a floor, not a ceiling. So we should be doing way better,” says Pate.

As the acting director general of the Indigenous Initiatives directorate at CSC, Marty Maltby says there could be potential to provide more services AT SHU.

However he emphasizes that the SHU exists to minimize the chance of staff or others being hurt in other lower security prisons.

“You need to recognize that the Special Handling Unit is a temporary solution to a risk. While it’s important for us to provide services and support at the Special Handling Unit, and we do, I would argue that we put lot of effort, a significant amount of effort, into actually moving them out of the Special Handling Unit, so what we have seen is significant decrease in the use of that unit,” he says in an interview with APTN.

By law, every case at the SHU is up for review every four months.

But according to Lacroix many inmates can spend well over a year there.

While the cut off for other forms of isolation in prison is now 15 days.

For many, the SHU is the epitome of a system that emphasizes punishment over rehabilitation.

“I don’t think we need a SHU, I think we need to offer services, manage these individuals and help them diminish the risk they might present, and I think that these services can be given somewhere else other than the SHU,” says Lacroix, the class action lawyer.

There are community based centres independent of CSC that exist to help Indigenous prisoners escape not only the physical prison they occupy, but the one within themselves.

But who gets to benefit from these places?

“Wasekun”- Cree for “When the sun comes out after a storm”

Nationally, Wasekun Healing Centre, in Saint-Alphonse-Rodriguez, Que., is one of six independently run healing lodges.

Started in 1988 by a group of First Nations Montrealers with experience in the correctional and justice systems, it’s currently located on a four acre property two hours north of the city.

“What we’re trying to do is make sure these guys, when they come out, they come out with a toolbox, I would say, of good medicines, good teachings, understanding of where they are in their life,” says Normand Guilbeault, a spiritual advisor at Wasekun.

“Healing isn’t easy,” says Kanienʼkehá꞉ka (Mohawk) Elder Dennis Nicholas “it never was. But it sure is doable, and there is no such thing as impossible.”

Guilbeault and Nicholas have just finished the daily morning meeting held in the medicine room with both provincial and federal inmates nearing the end of their sentences.

Wasekun may be a healing centre, but it’s also a minimum security prison.

Here they call the inmates residents.

Ricci Abram, 47, is one of them.

“My stay here has been great, it’s helped me to heal some of my traumas from my childhood that I hadn’t really dealt with as fully as I thought I did, because we were able to deal with it through counselling and ceremonies that elders provide here that I wasn’t getting access to in regular institutions.”

Abram’s story is a familiar one here.

Intergenerational trauma passed along from residential schools.

Absentee parents.

Substance abuse.

“It hurts to look back and to see the damage I’ve caused,” Abram says.“I don’t want anybody else to do that and learn their lesson after it’s too late.”

“Because you can’t take your mistake back. There’s no excuse for my actions, but I’ve learned that there are reasons.”

Abram has spent 20 years in prison for first degree murder.

The Oneida man spoke to APTN on the condition that we not go into details about his crime.

“I had to stop and turn and look in the mirror and do a real deep inventory on what led to me to go down this road of negativity and darkness and drug use and alcoholism finally culminating in the ultimate horrendous act of violence,” he says.

“I knew I had to fix that, I had to heal that. So I wouldn’t have any more victims, so I wouldn’t be hurting no people,” Abram adds.

Abram has spent much of the last year here learning ceremony from Nicholas.

It helps that they are both a part of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) confederacy.

As the possibility of parole draws nearer, Abram has a clear vision of what he’d like to do when he gets out.

“I want to help people to heal, to be able to let go of stuff that’s holding us down, that’s been holding our people down for generations, and to show them that if I can do it, anybody can do it.,” he says.

But how many Indigenous inmates are getting help at healing centres like this?

According to correctional watchdog Ivan Zinger, the vacancy rate is at 40 per cent.

“I’m of the view that given the track record of corrections that we should consider looking at alternative options,” he says.

“We need huge amount of resources to be reallocated from Correctional Services of Canada to Indigenous communities and groups to try and to improve those correctional outcomes that are so terrible.”

Technically known as a “section 81” healing lodge, Wasekun is funded by CSC, but as an Indigenous organization, is free to run their own healing programs.

Meanwhile, a recent report shows that independently run healing lodges like Wasekun make a difference.

Specifically, offenders who completed Indigenous cultural programs at a section 81 healing lodge had a 54 per cent lower risk to return to prison.

Other healing lodges that are operated by Corrections Canada had a 29 per cent rate.

“I find that elders here and the helpers are more respected here, their opinion matters,” says Abram, who prior to Wasekun spent time in a lodge run by CSC.

“The management is really more open to our culture and our beliefs. And the wall still has to be there, but it’s not as big, not as high, not as thick.”

Maltby says the pandemic made getting people into healing lodges harder.

But he says that’s changing.

“Over the last few months, we’ve seen an increase, a significant increase, I would say in most of our healing lodges, hopefully I would say by the end of next year, this time next year, if not earlier we’ll see them as well as possible.”

Maltby says taken together, corrections run and independent lodges are at about 70 per cent capacity.

Wasekun says that as of early March, they were at 50 per cent capacity.

Since Wasekun gets money from CSC per resident, it means they only have half of their ideal budget.

“It has implications on everything,” explains director general Dominique Tremblay in French.

“For example, cords of wood, we have sacred fires every day, well wood, it’s $100 for a cord of wood, if it’s 15 residents or 30 residents, there’s fires to build every day.”

Wasekun is also in need of renovations, large and small.

They recently had to go to the bank for financing to fix the roof.

Meanwhile, inmates can be on the waiting list to join the healing centre from six months to two years.

“Every day we receive applications from inmates in penitentiaries that could be transferred here, that are accepted to come here, and we are waiting for their transfer. What is the hold up? We don’t know yet,” says Tremblay.

One issue that may hold male inmates back is that in order to go to a healing lodge, they must be classified as minimum risk.

In 2018, the supreme court ruled that the tool used to decide security classifications discriminated against Indigenous people.

And last year, the auditor general released a report stating that the process for assigning security classifications “…results in disproportionately high numbers of Indigenous and Black offenders being placed in maximum-security institutions.”

Also, when the process does determine an Indigenous inmate is minimum risk, corrections staff are 13 per cent more likely to override the risk rating to place Indigenous men in higher security.

For Indigenous women, it was even higher, at 23 per cent.

CSC says they have put into place an automatic review process for security overrides by staff.

As for the much-maligned security classification tool, “We engaged with the University of Regina to develop a project that’s going to look at that classification process overall,” says Maltby.

The research towards a new classification began in 2019 and is expected to take five years.

Correctional watchdog Ivan Zinger says his office first raised the classification issue 20 years ago.

“The inertia and inability of the service to reform itself is such that you have to wait decades to see changes and all during that time we have to remember that Indigenous people were probably over classified and sent to higher security than necessary,” says Zinger.

Recently calls for some of that money to go to other resources have only started to get louder.

“I won’t debate whether or not we have significant resources dedicated to this, but I will say that I think, again, part of the challenge we have particularly when it comes to recidivism pieces, is also that we need to work with communities and other partners to develop better strategies to keep people in community longer and safer,” says Malby.

When pushed about the long timeframes it takes for corrections to make changes, Maltby says, “It’s still not good enough, but I’m hopeful from where I sit, if we’re actually developing a [Indigenous] Justice strategy, if we’re actually looking at new ways and new approaches to section 81 and section 84 [laws for the release of Indigenous inmates into communities and organizations] and doing some of those things, the results of long term results will be better.”

Earlier this week, Kathy Neil, a Métis woman, was named the first deputy commissioner for Indigenous corrections.

The correctional watchdog first made the recommendation for the position to be created over a decade ago.

The Northwind Man

Daryle Kent may have spent most of his life behind bars.

But he has another name now, one that he hopes guides him in his new life: Keewatino Ininni.

“It was given to me in a ceremony as requested by my eldest brother. It means north wind man.”

The north wind is known for being cold.

Often spoken in reference to a shifting of seasons, it is a wind of change.

“You feel the north wind when it blows, right?” says Kent, a knowing smile briefly making an appearance. “Since I’ve been in prison, I’ve developed my voice. I’ve learnt how to use my voice. For at times, stupid things. To create havoc, or to hurt someone’s feelings. But I’ve also gone through that stage where I’ve learnt to use my voice to express the positive things in life.”

As a Wasekun graduate, Kent credits Elder Dennis Nicolas for his renewed focus on positivity.

Going forward he’s hoping to get into a trade and to visit some family he hasn’t seen in decades back on Brokenhead Ojibway Nation.

“They have developed on their own without me. But I got to catch up to them…with them.”

For now, the northwind man will keep on moving.

Driving.

He’ll just need to stay within his 100 kilometre radius for a little while longer.