Five years ago, the RCMP created a special unit to clear the way for B.C’s major resource extraction projects.

An APTN investigation digs deep into C-IRG: Community-Industry Response Group

The Mountie with the red can of mace bats a guitar away as a colleague flings it past him. The instrument lands in the dirt.

Another officer instantly smashes it to bits with a stomp before a fourth officer, with the word “MEDIC” etched on his back, kicks it into the bush.

A few metres away, Mounties douse protesters with streams of pepper spray. They rip surgical masks off faces in the crowd, knock off their hats and rub the burning chemical agent in their eyes.

The self-styled forest defenders, protesters against old-growth logging on Vancouver Island’s Fairy Creek watershed, absorb dose after dose on this warm August 2021 morning.

An observer weeps as Mounties threaten to arrest reporters.

“You do one more thing and I’ll dose you, bitch,” a Mountie allegedly told independent media producer Kristy Grear, according to court files. “There was no name tag or badge number displayed on the officer’s uniform,” the documents claim. “However I did observe a so-called ‘thin-blue line’ patch on the officer’s uniform.”

Video: @arvinoutside and @gavinvrose/Instagram

This is how the Mounties of the Community-Industry Response Group (C-IRG), a secretive industry defence arm of the B.C. RCMP arrive to dismantle blockades: armed with guns and mace, name tags ripped off, faces hidden, thin blue line patches emblazoned on their chests.

Police arrive with howling dogs, helicopters, drones, chainsaws, axes, an excavator, jackhammers, angle grinders and fancier gadgets like thermal imaging cameras.

“I was shocked to see those officers,” said Virginia McNab, a server and mother of three, in an affidavit. She claimed she planned to peacefully protest at Fairy Creek last summer but, instead, ran into a dozen Mounties deployed by the C-IRG.

“They were in blue and black, had facemasks, were in full combat gear, wearing sunglasses so you could not see their faces, had guns on their hips and had handcuffs,” she claimed. “It was clear that they were there to enforce an injunction by any means necessary.

“We were very clearly peaceful and they seemed not. As a woman facing a number of faceless men, I was terrified.”

Prominent First Nations activists call them “Indian fighters” and “oil and gas mercenaries,” but few know what this outfit is, why it was created, or how it operates.

APTN News spent months investigating the C-IRG, obtaining more than 4,000 pages of court files and releases from more than two dozen federal and provincial freedom of information requests.

APTN uncovered a broad suite of allegations against the unit that include intimidation, torture, brutality, harassment, racism, theft, destruction of property, arbitrary detention, inhumanity, lying and deceit.

The investigation obtained evidence of vast spying — including casual surveillance of law-abiding groups engaged in the democratic process — collusion with private security, collaboration with industry lawyers and wilful violations of RCMP policy.

Some of the allegations are backed by evidence and will be tested in court. Others aren’t. Some have already been proven. The unit denies them.

These are the fruits of that investigation.

These are the Mounties behind the thin blue line.

The pipeline police

The B.C. RCMP website offers

only three short paragraphs about the C-IRG, saying it “was created in 2017 to

provide strategic oversight addressing energy industry incidents and related

public order, national security and crime issues.”

But the C-IRG’s foundational policing plans reveal the real reason

the outfit was created: to protect pipelines, specifically the Trans Mountain

expansion and Coastal GasLink.

These documents, obtained by APTN through access to information,

indicate the force did this independently, without briefing or getting approval

from politicians, which the province’s then-solicitor general corroborated in

an email.

Rather, it was the B.C. RCMP’s commanding officer who directed the

establishment of a gold-silver-bronze command structure “for operational

oversight, planning and coordination” of the Trans Mountain project in December

2016, according to the plans.

This was the C-IRG.

The three-tiered incident

command system given to the unit is supposed to correct the incompetence

displayed in violent police attacks on First Nations in places like Oka,

Gustafsen Lake and Ipperwash.

Under this scheme, the gold commander, the unit’s top Mountie,

sets strategic objectives and deals with bureaucrats and RCMP higher-ups.

This frees the silver commander to oversee daily operations,

including enforcing injunctions and planning raids.

Bronze commanders then deploy the resources and execute the silver plan.

Under the C-IRG strategy, each of the RCMP’s regional districts in B.C. would have a bronze commander. Each of these commanders would be backed by a sub-bronze commander located in every detachment in every district.

Bronze commanders would also be appointed based on function.

For example, the bronze intelligence commander is tasked with spying on protesters, conducting threat assessments and reporting to the gold and silver leaders.

Chief Supt. Dave Attfield, the first gold commander, described the C-IRG’s “preferred” outcome as this: facilitating pipeline construction with “no criminal acts, no injuries to any person, no damage to property” and no violence.

“Members of the public can enjoy lawful use of public and private property, employees of CGL, TMC [Trans Mountain Corp.] and LNG Canada are able to go about their business unmolested,” he wrote in the gold plan, “and demonstrators can publicly, peacefully and lawfully express their views.”

The plan labels an “acceptable” outcome as one that includes “some disturbance of the peace,” minor interference with pipeline construction and some injuries due to “personal issues or accidents.” An “unacceptable” outcome would include violence, riots and rumbles.

The plan also reveals other elements of the unit’s operations.

For example, The C-IRG has no set budget. Extra policing costs are covered by the local impacted detachment through the standard federal-provincial contract funding stream.

Thus, all C-IRG Mounties are volunteers who occupy their position in addition to their normal rank and job. C-IRG deployments are secondary, as-needed duties for which the officers are paid overtime.

For example, Jeffrey Ausmus, who filed an affidavit explaining why he ordered officers to mace the Fairy Creek protesters, holds the rank of staff sergeant but also serves as watch commander for a C-IRG Quick Response Team (QRT).

Attfield also decided the Mounties would communicate directly with industry officials and, “where necessary” share police intelligence with them.

The one thing the C-IRG wouldn’t do, according to his plan, was ask corporate leaders to pay extra for this new unit’s tailor-made services.

Rather, it says discussions about “supplemental funding for policing operations” should be left to provincial and federal government officials, who can then turn to the RCMP for information about costs.

Attfield’s rationale for giving the C-IRG this structure — sub-bronze commanders in every detachment, bronze commanders in every district, and silver and gold commanders at provincial headquarters in Surrey — was that it would be “scalable and subject to change based on protest-related activity.”

In other words, a network of special Mounties would be formed across B.C., sprawling out from headquarters into remote regions, like the sticky strands of a spider web.

These strands would intertwine intimately with petroleum firms, so when Attfield’s anticipated but unspecified anti-pipeline “protest-related activity” broke out, the C-IRG would spring into action.

The Mounties would be ready.

And they would be everywhere.

Snooping on democratic groups

But the next question was out of Attfield’s ambit as gold command: What happens when the unit needs to act?

This was left to Chief Supt. John Brewer, who served as silver commander from 2017 until June 2021, when Attfield retired and Brewer became the group’s top Mountie.

Brewer is a nearly 30-year veteran involved in domestic and international policing operations including in Afghanistan, according to court files. He’s a former member of an RCMP Emergency Response Team (ERT), the force’s militarized SWAT units.

His silver operational plan begins with a detailed timeline before offering “general comments on TMEP [Trans Mountain expansion project] and CGL opposition.”

The section reveals the C-IRG has been casually monitoring the political activity of peaceful law-abiding groups based on fears that unknown extremists, professional protesters and agents provocateurs may use violence to support the cause.

“While Police are impartial, it is operationally necessary to have awareness of opposition to the oil and LNG pipeline project,” the plan explains. “It is understood that the majority of individuals and groups will express their opposition through lawful advocacy, protest and dissent.

“As noted above, some communities in British Columbia — or in some cases, individuals within those communities — are opposed to any pipeline expansion.”

The plan then lists these pipeline opposers who’d come under state snooping, describing their resistance as “entrenched” and saying again they “openly oppose the TMEP pipeline.”

Brewer named the Burnaby Residents Opposed to Kinder Morgan Expansion (BROKE), Coquitlam Residents Opposed to Kinder Morgan Expansion (CROKE), Coastal Protectors, Climate Convergence Metro Vancouver, 350_Vancouver, Wilderness Committee, Greenpeace, Raincoast Conservation Foundation, Living Oceans, Pipe Up and Water Wealth.

Other known open opposers included the Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish, Kwantlen, Aitchelitz, Cold Water and Upper Nicola First Nations, according to the document.

“Although these First Nations opposes [sic] the expansion,” Brewer wrote, “they are pursuing that opposition in the courts and have not advocated unlawful action in defense of their position.”

Meanwhile, on the CGL front, he listed Office of the Wet’suwet’en, the Unist’ot’en Camp, the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs and multiple individual members of the Wet’suwet’en Nation.

His plan says he expected all these groups to be peaceful.

There was a “but” coming.

“However,” the plan adds, “given some past events there could be public order issues arising from radical environmental activists and provacateures [sic] who may attempt to escalate an otherwise peaceful protest.”

In addition to radicals and agitators, Brewer argued “some groups and individuals” already pledged to block pipeline expansion, presumably a reference to groups like the Tiny House Warriors and Unist’ot’en Camp.

Brewer also worried “a few individuals” expressed “extreme views,” which he claimed included threats of violence “in a couple cases.”

Despite that, he noted that “no on-line intelligence has been found which gives specific information on the nature or numbers of potential threat actors for the construction at TMEP or CGL.”

Moreover, both pipelines were designated national critical infrastructure by the federal government, meaning a federal counterterror squad, known as an Integrated National Security Enforcement Team (INSET), “is monitoring protest actions related to these projects.”

Yet Ottawa had no specific national threat level for the projects because the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre (ITAC), housed under the country’s top spy agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), hadn’t probed the topic yet, according to Brewer.

With all this in mind, the new unit’s first mission would be to “protect lives and reduce potential for injuries to workers, demonstrators, the general public and police officers; and minimize opportunities for persons to commit criminal acts against persons and property in the area of TMEP and CGL construction and operations.”

But if a federal counterterror squad authorized to conduct disruptive stings was already spying on protests, why set up a secret quick-strike industry defence force to do similar things?

The answer comes when Brewer’s plan describes the “end state” the C-IRG hoped to reach.

“Any intent of a violent protest will have been discouraged by police planning and preparations,” he wrote. “If a violent protest occurs, it will have been interdicted early and full investigative resources will be brought to bear. Public safety, security of property and public confidence will have been maintained by police planning and preparations.”

For the C-IRG, it’s good planning and preparation. Standard police work. Nothing more.

For the critics, it’s countersubversion of democratic groups and colonization of unceded Indigenous territory.

APTN requested an interview with senior B.C. RCMP officers a week before posting this story but no one was made available.

Tiny House Warriors: The C-IRG in action

A man with a beige hat and red paint on his palms burst through the doors of the grand hall at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops.

It was Isha Jules, member of the Tiny House Warriors and brother-in-law of prominent activist Kanahus Manuel. The paint represented the links between resource extraction and violence against Indigenous women and girls.

Behind the closed doors, former top court judge Frank Iacobucci was chairing the latest round of court-ordered meetings aimed at fulfilling Canada’s duty to consult with First Nations prior to building the Trans Mountain expansion through their lands.

It was December 2018. Outside the hall, Mayuk (Nicole) Manuel and Snutetkwe (Chantel) Manuel — daughters of the famed activist, politician and Indigenous rights defender Arthur Manuel — splashed red paint across the walls.

Within minutes, the C-IRG was there. Members of its Divisional Liaison Team (DLT), mediators trained in negotiation who are often Indigenous, arrived followed by a QRT, the multipurpose quick-strike unit tasked with answering urgent industry concerns.

The Mounties hauled the trio off, and eventually, in early 2022, they were convicted and acquitted on several charges stemming from the tussle.

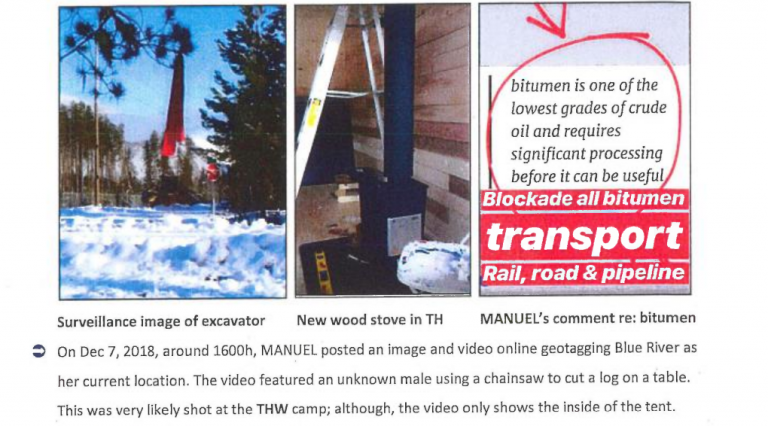

While it was a minor incident drawing mostly local attention, for the C-IRG the crashing of the Iacobucci meeting represented the first in a series of escalating actions.

While its operations for Trans Mountain remain largely undocumented, the unit faces the same allegations that later surfaced elsewhere and recently elicited concern from the United Nations.

The C-IRG has been accused of brutality, collusion with private security firms, and excessive surveillance against the Tiny House Warriors camp, which is blocking pipeline construction by occupying unceded Secwépemc territory near Blue River.

For example, group spokesperson Kanahus Manuel is suing a Mountie named Cpl. Todd Bowden, who she alleges broke her wrist when applying a wrist-lock technique during an October 2019 arrest, according to the provincial court registry.

The allegation has not been proven in court.

APTN however has confirmed C-IRG used so-called “pain compliance techniques,” which included gouging a protester’s eyes with a face hold, at Fairy Creek.

APTN also confirmed the C-IRG receives and uses intelligence from private security agents, who are almost without exception veteran ex-Mounties, and works closely with them during police operations.

The man who Jules brushed past in the university grand hall was Tim Neuls, Trans Mountain’s regional security manager who spent 28 years with the B.C. RCMP before moving into private security for De Beers in the Northwest Territories, according to his LinkedIn page.

The Trans Mountain security guard posted outside the room, whom the two Manuel sisters were convicted of assaulting, was Peter Haring, a former cop mentioned in a Civilian Review and Complaints Commission (CRCC) report from 2020.

The watchdog agency had opened the probe after a civil liberties group alleged the B.C. RCMP mounted a counterintelligence campaign against peaceful pipeline opponents in 2013. In that instance, the force was cleared.

But the commission raised concerns over the RCMP’s tactics, which included covert spy operations and infiltration, urging the force “to exercise restraint in its surveillance and intelligence-gathering activities when the threat level is otherwise determined to be low.”

Haring is mentioned multiple times in internal Trans Mountain records obtained by Joe Killoran, the lawyer who represented the accused in the university dust-up.

When the Trudeau Liberals bought the pipeline in 2018, it became a Crown corporation, meaning it’s subject to laws governing federal arms of the state. This includes the Access to Information Act.

The documents released to Killoran’s law firm, though heavily censored, reveal Trans Mountain maintained a secret corporate espionage regime engaged in open-source spying on people the company dubbed “core persons of interest.”

The company’s intelligence reports include assessments and deductions that magnify divisions in the Indigenous land back movement and, at times, approach defamation and smear.

“New information about a core [person of interest] confirms the Tiny House Warrior Camp is attracting some fringe and more extreme Indigenous activists some of whom have been alienated from their own communities,” one intelligence deduction asserts.

The “information” that supposedly confirmed this fact was a Facebook post and a few argumentative Facebook comments made by a group member, which enabled Trans Mountain’s spies to identify them.

The reports contain no evidence the ex-Mounties in charge of Trans Mountain’s security and surveillance operations shared this intelligence with current members of the force.

However, APTN has confirmed in Wet’suwet’en territory and Fairy Creek that the RCMP received intelligence from other firms run by different ex-Mounties, and even used this information in court. Those reports are discussed below.

But back in Secwépemc territory, the Tiny House Warriors allege this fusion of corporate-state policing “escalated aggressively” over the years.

The warriors helped compile a joint submission to the UN, obtained by APTN, alleging they “have been the target of constant surveillance, harassment, and intimidation” by the RCMP, C-IRG and Trans Mountain’s security agents.

“Most concerningly, these TMX [Trans Mountain expansion] personnel installed massive, multi-spectrum, remote-operated surveillance towers, metres from the THW [Tiny House Warriors] village site, arrayed with cameras, automated sensors, loudspeakers, and floodlights,” reads the Nov. 23, 2021 letter.

“One floodlight is trained at all times on the sleeping quarters of Kanahus Manuel — a blatant intimidation tactic. It is unclear to what extent human operators are involved in monitoring or evidence collection.”

The letter also says it’s unclear who owns these peculiar devices, what sensor technologies they use, what information they gather and where this information is stored.

“What is clear,” the submission adds, “is that this intrusive, 24/7 monitoring and remote multi-spectrum surveillance technology could represent a serious violation of privacy, civil liberties, human rights and Indigenous rights.”

Finally, unlike on Wet’suwet’en territory or Fairy Creek, the C-IRG hasn’t conducted full-on raids for Trans Mountain. But that doesn’t mean it’s been ruled out.

Force has been contemplated, but “police believe this could escalate the situation,” according to internal B.C. government memos from November 2021 obtained through FOI.

Trans Mountain refused an interview request for this story.

Wet’suwet’en territory: The C-IRG unleashed

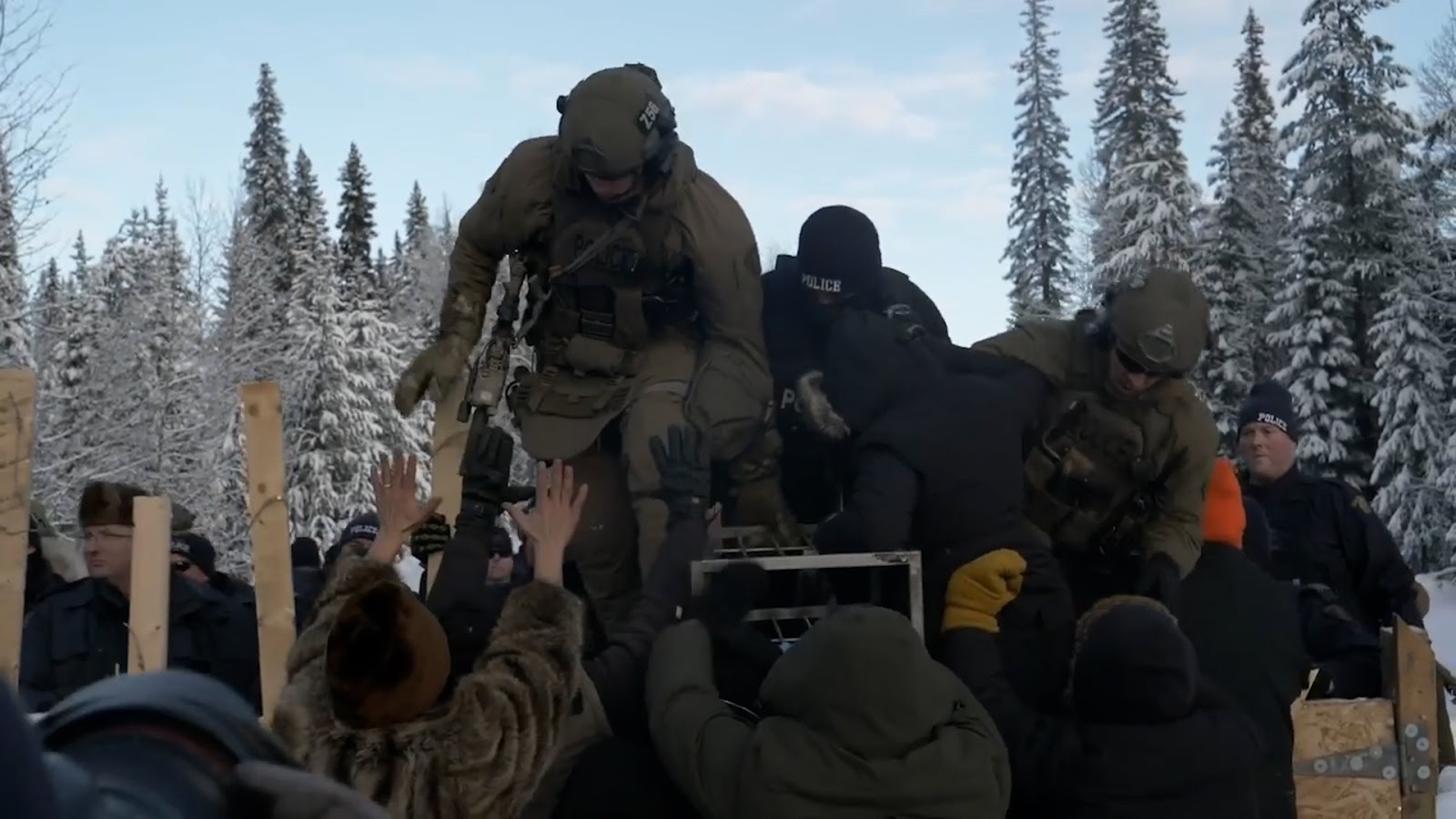

A Mountie in “ranger green” SWAT gear sailed over the barbed-wire barricade with a carbine rifle dangling from his shoulder on Jan. 7, 2019. He reached for the nearest protester and wrangled him into the snow.

More officers flooded over the wooden structure like a wave crashing over a wall.

The guys in green took their posts as “lethal overwatch,” scanning the crowd for threats, fingers close to the trigger.

Riot cops in blue started dismantling the wood barricade, arresting people who got in their way — and just like that, the blockade was breached.

Only weeks after the Kamloops door-crashing, here was the C-IRG executing its first of three all-out militarized raids on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory.

APTN’s investigation has unearthed key documents offering a rare look behind the scenes of this major tactical operation.

These include an investigative logbook that contains notes handwritten by a civilian member of B.C.’s INSET, the counterterror squad, who was attached as a scribe to Brewer’s silver command.

APTN also obtained Attfield’s handwritten notebook, C-IRG emails, Brewer’s strategic raid plan for CGL and an “after action review” commissioned after the unit came under fire for alleged heavy handedness and strongman tactics.

Taken together, the files show that in 2019 the Mounties employed unorthodox methods, violated RCMP policy, strayed from their assigned mission, obsessed over media, tried to manipulate coverage, deceived Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and made unnecessarily inflammatory comments.

The day before the raid, a roomful of Mounties gathered to hear their mission statement read aloud in Houston. A few dozen kilometres east, Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and supporters manned a checkpoint controlling access to a remote logging road.

The Mounties watched and listened as the C-IRG’s spymaster, bronze intelligence commander Sgt. Phil Simkin, delivered his threat assessment.

He offered the officers a briefing on both the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre and Gidimt’en Checkpoint, confirmed the presence of reporters, suggested the camps were well-provisioned and self-sufficient, and warned that Jan. 8, 2019 was to be an international day of action, according to meeting notes.

He told them the group claimed to be non-violent and that there’d been no violence. But he also mentioned the group’s “affinity to the ‘Way of the Warrior,’” according to the notes.

“Ten to 20 firearms are in the camp as they hunt,” the log records Simkin saying, adding that all were scoped and used for protection from bears. “No information they are stockpiling weapons.”

Attfield’s handwritten notes demonstrate similar concerns. On the morning of Dec. 10, 2018, the gold commander was tracking protests and helping map an enforcement plan should the pipeline builder obtain an injunction.

Assessing the situation, he claimed there were “some radical and potentially violent elements clearly in support” of the Unist’ot’en Camp, whose funding sources he was also particularly interested in.

It’s not clear who he meant, but the notes mention Extinction Rebellion Vancouver, Indigenous Climate Action, Greenpeace, Rise and Resist, and now for the second time the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs.

After the injunction was handed down, Attfield and Brewer solidified the C-IRG’s multi-pronged, three-phased raid plan over a series of meetings in late December.

Brewer wrote it up in a document titled “Concept of Operations — CGL: CONFIDENTIAL.” This secret plan says phase one would be handled by the local detachment while C-IRG hung back, liaised and watched in the background.

Phase two would be the show of force. An RCMP riot squad known as a Tactical Troop (or Tac Troop) would swoop in alongside a paramilitary SWAT unit known as an Emergency Response Team (ERT) followed by a dog unit, liaison team, criminal investigators, transportation and logistical support.

These would be backed by RCMP strategic communications specialists, a helicopter equipped with an infrared thermal imaging camera known as a FLIR, a surveillance drone operator and an obstruction-removal unit.

Phase three would be handed over to a quick-response squad, like the ones that responded to the Kamloops call and pepper sprayed the Fairy Creekers, for “sustained operations” for the pipeline company.

On paper, they thought of everything. The plan was comprehensive. Every contingency was covered. The troops even received Indigenous cultural sensitivity training and a briefing on injunctions. It was to be the paragon of policing.

But the C-IRG, in executing the plan, deployed tactics that would reappear at Fairy Creek and in subsequent raids on Wet’suwet’en territory, drawing condemnation from the media, the public and the court.

During the afternoon of the 2019 operation, the C-IRG commanders gave Sgt. Kevin Bracewell, the Tac Troop commander who, like Brewer, has experience policing in Afghanistan, permission to use the obstruction-removal unit against people who had attached themselves to a bus.

The notes indicate a mechanic would be brought in to remove part of the bus the activists were attached to. The notes offer a simple comment in the record of this decision: “against policy.”

It isn’t clear what element of bus dismantling went against policy, but the relatively minor event offers a snapshot of some of the C-IRG’s controversial tendencies.

The unit knowingly violated RCMP policy, destroyed or dismantled protester property, and relied on third-party industry contractors as well as unorthodox techniques to remove activists engaged in passive resistance.

These all became hallmarks of the unit’s operations to protect logging at Fairy Creek.

But back on Wet’suwet’en territory, there was fallout following the crackdown on the logging road.

The raid garnered public outcry for its paramilitary style, and, as a result, the RCMP commissioned a post-operation review in which the force assessed its own conduct. It wasn’t made public. Until now.

The review, obtained under access to information, reveals the Mounties who heaved themselves over the blockade strayed from their assigned mission in something the reviewers dubbed “task creep.”

The rifle- and sniper-wielding ERT officers had one mission and one mission only: Back the Tac Troop with lethal overwatch. So when they breached the blockade and started grabbing protesters, they violated their marching orders.

“The unique uniforms — described as ‘army’ green by Unist’ot’en observers, body armour, head gear, firearms and other equipment of the ERT members — no doubt contributed to the perception among some observers that the RCMP carried out a militarized or tactical operation or otherwise used intimidation against protestors,” the reviewers noted.

The review ducks the issue by concluding there was only “perception” of intimidation, not the fact of it. Nevertheless, it proves that Mounties engaged in unnecessary confrontation with non-violent activists while heavily armed and geared for war.

On the same note, the reviewers justified the use of lethal overwatch by arguing it’s an innocuous support role that sounds frightening to civilians, but doesn’t mean the cops were ready to shoot and kill people.

But there is ample evidence, some of it discussed above, that the Mounties considered the pipeline opponents to be, potentially, warrior extremists and violent radicals with guns near at hand.

Attfield’s notes show the C-IRG, in fact, believed the ERT was required “given exposure potential to threat.”

The files also reveal the unit’s efforts to control and manipulate the press through “strategic communications” and illegal exclusion zones. The unit frequently tried to manage its image and closely monitored coverage.

The day after the raid, C-IRG commanders gathered for a briefing.

The top agenda item was the media.

“We won’t necessarily win the media,” Brewer told Attfield, according to the notes, “but have to counter everything negative they say.”

It was on this day the commanders decided to further curtail reporter access. Meanwhile, their own RCMP spin machine kicked into high gear and cranked out the police version of the narrative.

“Media is media,” the scribe recorded someone saying. “CBC put out our media release.”

That morning, Attfield decided to keep reporters off the road, citing “safety issues.” Later, Brewer told someone to ask Dawn Roberts, a 20-year RCMP communications official and former Global News journalist, if she wanted video of activists lighting fires “for strategic comms purposes.”

Then Brewer decided the cops would share surveillance footage obtained via drone and helicopter with CGL. In fact, the investigative log records multiple intelligence-sharing meetings between police and the company over the course of operations.

After that, the unit set about curating an hour-long video montage of the raid to show Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, who were shocked and furious at the police aggression.

However, the scribe also recorded someone from silver command saying of the chiefs, “They didn’t get the video of police being heavy handed and disrespectful.”

A civilian member of the RCMP meticulously recorded notes like these during the planning and execution of the raid in 2019. These notes are from a meeting shortly after the operation. Photo: ATIP

Over the next couple days, the restrictive media policies continued. “Media is by invitation of the chiefs. No to full access.” The commanders monitored coverage closely, raising concerns about an interview that “was critical of our actions.”

The commanders pushed back, arguing police video supported their side of the story, while also heavily limiting journalists’ ability to verify the claim. They tried to hide their actions from the hereditary chiefs, who they didn’t want driving by while police dismantled a checkpoint.

Meanwhile, RCMP communications had prepared and pre-approved multiple press releases by Dec. 27, 2018 — well before the raid. One such missive moved two days before the operation.

The RCMP attempted to bolster its claim to have jurisdiction on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory by offering its interpretation of the landmark 1997 Delgamuukw decision. Instead, the force’s colonial arguments further inflamed tensions.

“It is our understanding that there has been no declaration of Aboriginal title in the Courts of Canada,” the Mounties declared. “The Supreme Court of Canada decided that a new trial was required to determine whether Aboriginal title had been established for these lands, and to hear from other Indigenous nations which have a stake in the territory claimed.

“The new trial has never been held, meaning that Aboriginal title to this land, and which Indigenous nation holds it, has not been determined. Regardless of the outcome of any such trial in the future, the RCMP is the police agency with jurisdiction.”

The RCMP was asserting a right to invade unsurrendered land. The tone and pointlessly political nature of the comments angered many, attracting so much backlash they had to be retracted.

The Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan hereditary chiefs launched this case in the ’80s, arguing they were distinct peoples who never ceded legal title to their lands. They struggled through a foreign legal system, enduring racism and insults in the lower court for years before finally achieving a favourable ruling.

While the police were technically correct no new trial was held to settle the issue, that’s because the high court counselled negotiations, which were abandoned after the province refused to talk in good faith.

Despite this, the provincial government has assessed the Wet’suwet’en Nation “as having strong Aboriginal rights and title claims,” particularly where the Unist’ot’en camp is located, according to a confidential memo sent to B.C.’s energy minister following the raid.

Coastal GasLink turned down an interview request for this story, saying via email, “We have engaged with the RCMP when workforce and public safety is at risk from illegal protest activities.”

Working with private eyes

Ram Sandhu breezed past the RCMP exclusion zone and headed toward Fairy Creek headquarters on a fine Friday morning of Aug. 6, 2021.

Here was a rather peculiar scene. The C-IRG maintained its exclusion zones with authoritarian resolve both on Vancouver Island and Wet’suwet’en territory. So why was this person let through?

Mounties turned back reporters, activists, elders, chiefs and members of the general public, only letting them through if they submitted to invasive searches.

But Sandhu was none of these things.

Sandhu was a private eye sent by Lions Gate Risk Management to secretly spy on activists for logging firm Teal-Jones. On this day, he wasn’t just allowed past the exclusion zone, he was “escorted by two RCMP members beyond” it.

In fact, court files show Mounties colluded with Teal-Jones’s private security agents and helped them infiltrate Fairy Creek camps to conduct covert surveillance operations then feed this information back to the RCMP.

APTN obtained Sandhu’s intelligence report filed after the infiltration mission was complete.

Once the Mounties escorted Sandhu and another private eye past the exclusion zone, the spies started filming and photographing everything, noting the protesters “appeared to be well organized and fortified.”

The spies lied when they got to Fairy Creek HQ, telling the person manning the post “they were just curious regarding what the protestors were protesting about and what the living conditions are at the camp,” according to the report.

After the ruse succeeded, they moved throughout the camp until met by someone “paranoid” who suspected a scam. They left swiftly.

Sandhu’s surveillance reports occasionally frame the activists as potentially violent, observing they “did not appear to be hostile” or “no hostility was shown.” Sandhu frequently photographed garbage or debris left around the camps.

But, for the most part, the spy just observed activists singing, dancing or smoking. One report says the video the private eye captured during a surveillance mission “was all submitted to RCMP to maintain chain of command.”

It’s strong evidence the C-IRG collaborates with private investigators, functionally offloading tasks like this one to ex-security, military and police personnel who move more freely in the private corporate world.

Lions Gate’s website proudly announces itself as a team of “former law enforcement, military, academic, and security industry specialists [who] provide unparalleled expertise and experience.”

Its president is Doug Maynard, another 30-year former cop with tactical and international experience. His biography says his work resulted in the RCMP’s adoption of the gold-silver-bronze incident management system.

The company’s website says Maynard accepted the president position, where he now helps resource extraction companies deal with “lawful and unlawful protest activities,” after retiring from the force.

His LinkedIn page says this was in June 2017, a few months after the C-IRG was established.

Similarly, on Wet’suwet’en territory last fall, an officer relied on a security guard’s report in court to try and beef up a case against Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Dsta’hyl (Adam Gagnon).

An affidavit filed by C-IRG Const. Benjamin Laurie bases its allegations on an Oct. 17, 2021 CGL incident report authored by Forsythe Security employee Ed Reinink.

Reinink is a former cop, and Forsythe Security’s top official is Warren Forsythe, a former 30-year Mountie who now provides private services for the energy industry.

This confirms private security firms consisting of veteran ex-cops helped the C-IRG in all three of its major operational theatres.

Fairy Creek: The C-IRG on trial

In Fairy Creek, 121 people are seeking a stay of charges based on the claim that police engaged in a concerted “campaign of fear and violence” that was “so shocking” the court must toss out the charges to protect its reputation.

APTN obtained the summary of these allegations along with approximately 80 affidavits sworn by people who allege the unit mistreated them, often cruelly and brutally, along with the company’s and RCMP’s filings.

Taylor Alsager claims the C-IRG subjected her to “stimming,” a psychological warfare tactic that involves using visual or auditory stimulus to disorient, destabilize and manipulate the target.

“This involved a police vehicle revving and using lights and sirens multiple times in the night. She also had her shade structure dismantled and was left in the sun without protection,” court documents claim. “She witnesses the use of pain compliance on another person to get them to release from a hard block.”

Tyler Arsenault claims he suffers “serious psychological injury” after Mounties extracted him from a protest device known as a sleeping dragon. His lawyers claim the extraction “can be fairly described as fitting the definition of torture” under the criminal code.

To remove protesters from these devices, which involve attaching one’s wrist to a pipe cemented into the ground, the Mounties would excavate a hole beside the pipe, jackhammer through the cement, then cut through the pipe with an angle grinder or saw.

Arsenault alleges his extraction went very wrong.

“They used pain compliance on him to get him into positions and covered him completely with a black blanket that smelled like gas,” court files claim. “He could not see or breathe. RCMP used a plank and a 4×4 piece of plywood over his entire body to compress him, pushing on his chest until he had trouble breathing.”

Once they jackhammered through the concrete, the man claims he cried out in pain before an officer named “Eugene” hit the sleeping dragon with a crowbar to break it, causing his arm to quadruple in size.

Zoe Basil claims she was arrested while atop a wooden tripod by a cop in a cherry picker.

“Ms. Basil experiences PTSD from the psychological tactics used by RCMP during her time at Fairy Creek and will testify to the unlawful use of exclusion zones, manipulation, and destruction of property,” documents claim.

The documents allege these aerial extractions were particularly dangerous and haphazard, relying on industry contractors to operate heavy machinery right next to people. One video shows police dumping an activist from a tripod almost on their head.

Video: Sharingsiteogb/Facebook, independentblackmedia/Instagram

Others allege they were “hot boxed” by police, meaning they were arbitrarily detained in the back of prisoner transportation vehicles that reached oven-like temperatures in the scorching summer heat.

Waseem Daniel-Hakhroo alleges he was running down a road with a shovel when a Mountie sprung from a vehicle and tackled him into a ditch.

“This was done without warning him to stop or attempting to arrest him or question him,” documents claim. “Mr. Daniel-Hakhroo was diagnosed with a non-displaced fracture of the fibula.”

Levi Rowan, a high school graduate, had clipped himself into a sleeping dragon while suspended in a tripod: what the protesters dubbed a “flying dragon.”

Rowan filed pictures in court showing an ERT member gouging his eyes and yanking his head during the extraction. Rowan claims the officer “stopped for a few seconds, and then did it again, but this time he grabbed my eyeballs, with his pointer finger and ring finger and with his middle finger he grabbed my nose and pulled back, straining my neck.”

In a responding affidavit the cops argued this was a perfectly acceptable application of “pain compliance” techniques.

Kimberly Murray claims the Mounties had her legally parked Land Rover towed into the exclusion zone then hauled off to a private impound lot controlled by Teal-Jones.

The logging company then refused to return it, or any other towed vehicle, unless the owner paid $2,500 and agreed to be potentially added as a defendant in legal proceedings. The timber firm set up a “protester phone line” run by its security agents that vehicle owners could call.

On the other side of the line, Laura Zimmerman, a Lions Gate staffer, would tell them Teal-Jones was exercising a legal self-help remedy known as “distress damage feasant,” and levying a $2,500-lien as compensation for alleged damages.

The company argues the scheme was legal, but the activists claim it was “organized theft” and extortion by the trio of police, private security and industry.

Other affiants claim to have witnessed police pocketing unattended protester property in the injunction zone. The Mounties claim anything removed was garbage.

Cheryl Newton claimed she witnessed a Mountie strip-searching young First Nations activists. She said she used to trust the RCMP and worked with them as a youth and family counsellor, which all changed at Fairy Creek.

“I am seeing now that the law seems to have given decision making rights to the RCMP and we have now become a police state,” her affidavit says. “This is appalling and disgusting that we have to live our lives in fear of terrorists that our tax dollars pay for.”

Journalists joined in, successfully arguing the unit’s heavy media control was unconstitutional — a tactic expected from authoritarian regimes, but not democracies.

“That level of police restriction on media movement and access at the Injunction Area was familiar to me from my work in China,” argued Global News journalist Paul Johnson in an affidavit. “The Chinese policing authorities decided who would be allowed to see what, where and when.

“It is not consistent, however, with the type of media access I have experienced in the United States or other democratic countries during protests or even during active criminal events.”

Meanwhile, the RCMP court filings tried to refute all this, offering a defence of the C-IRG’s behaviour. While it applies only to Fairy Creek, the squad used the same tactics elsewhere.

The Mounties argued protester tactics forced the cops into unorthodox and occasionally risky methods. They returned to the now-familiar suggestion the activists were “extreme” potentially foreign-funded professionals.

Sgt. James McLeod, the country’s most experienced ERT leader who was deployed to oversee aerial extractions, suggested they were also unstable drug users.

“Numerous Narcan resuscitation kits have been located at the camp sites and I have observed frequent drug use,” he claimed. “Inebriation by any drug exacerbates the dangers posed to the protestors and officers to extricate protestors from tree sits, tripods, sleeping dragons, and other structures.”

Brewer filed four affidavits to try to defend his decisions and the conduct of his subordinates. In his telling, the activists had launched an “increasingly co-ordinated and well-resourced” campaign of illegal blockades, frequently putting themselves at risk and requiring specialized responses.

The Fairy Creek files reveal the same extensive surveillance, including through social media and aerial monitoring, and confirm Brewer, now as gold commander, overrode RCMP policy by ordering C-IRG officers to remove their name tags and permitting them to refuse to identify themselves.

“This was only at Fairy Creek and not extended to any other duties,” he said, claiming he was scared Mounties may be bullied or “doxed” online. Under Brewer’s new policy, C-IRG officers would identify themselves unless “engaged in policing activities that required their attention.”

Since all enforcement could theoretically be considered such activity, they had an effective loophole to elude identifying themselves at any time.

Brewer’s affidavits also confirmed the C-IRG set up floodlights at night. He argued they were for “situation awareness on dark logging roads” and not psychological intimidation.

“Enforcement is futile” if police couldn’t control road access through exclusion zones and personal belonging searches, Brewer added. He claimed the searches were voluntary but also mandatory to cross the exclusion line. “If an individual does not consent to a search, they are simply turned away.”

He said Fairy Creek was the largest and most complex operation he ever commanded, and that the C-IRG was being smeared by a non-Indigenous movement co-opting the language and symbolism of First Nations resistance.

“I am proud of the general professionalism, compassion and restraint shown each and every day by my members,” Brewer said.

But the activists succeeded in their application, at least at first. A lower court judge was so concerned by all this he cancelled an injunction, saying he “considered the infringements of civil liberties to be unjustified, substantial, and serious.”

But the appeals court reinstated it, saying, “Significant, organized, deliberate and persistent defiance of the law and court orders is a serious threat to the rule of law which is both the foundation of a functioning democracy and the refuge of every citizen.”

The appeal court also said the judge’s concerns were legitimate, but that he erred in law. People who’ve been mistreated by police have access to other remedies. They can file to have their charges stayed based on abuses of basic human rights, the appellate court said, which is the proceeding now back before a different judge.

So, five years after it was formed and tens of millions of dollars later, in a peculiar reversal of fate, the C-IRG is being put on trial in a novel and potentially precedent setting case by the very same people it arrested.

On one hand, the C-IRG argues its tactics were necessary given the at-times-literally entrenched nature of numerous illegal blockades.

On the other hand, activists contend police engaged in a sweeping and systematic campaign of human rights abuses, approved or willfully ignored by commanders, that has no place in a democracy.

A judge will eventually decide.