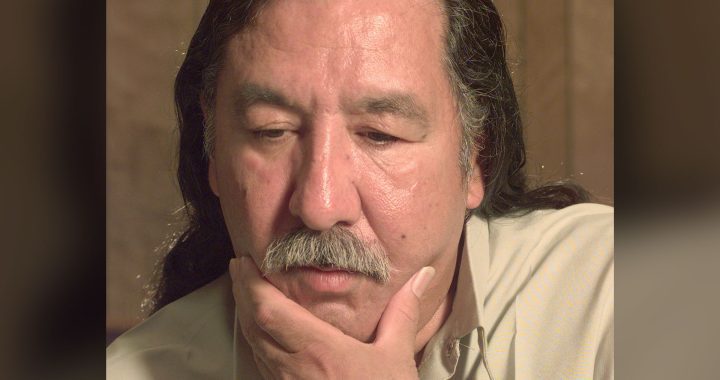

At one time Roy Dahl had 13 biological siblings – but he didn’t grow up with any of them.

He was born in Red Lake, Ont., 570 kilometres northwest of Thunder Bay, but was taken from his family to attend St. Mary’s Residential School.

He was plucked once again from there and placed into the foster care system before being adopted by a white family.

Dahl was too young to remember his separation from his birth family, but over the years pieced together the movement in his early years.

“My brother said that they (Indian agents) just showed up at our door and said your children are coming with us, he went because I and my younger sister were taken.” Dahl said.

“My adoptive brother, the way he described it, it was almost like adopting a puppy. His family went to the children’s home, and thought oh he looks like he needs a good family.”

(Dahl with his adoptive mother. Photo courtesy Roy Dahl)

As a Sixties Scoop survivor he is part of a class-action lawsuit.

“We are going to spend our whole lives processing all of this, because we all feel a sense of alienation. We don’t feel like we belong,” he said.

Dahl recently attended the Sixties Scoop information session in Yellowknife where he found both comfort wrapped in confusion.

He was amongst some survivors who hoped to include claims of abuse in the lawsuit.

“If there are 2,500 approved claims and we were to press forward those abuse claims, we would have to prove in each situation that abuse happened. But, here is no commonality in our stories and the evidence would not be as clear as in Residential Schools which had a smaller group of perpetrators,” Dahl said.

Dahl recalled being subjected to harsh punishments not enforced on his adoptive siblings.

“I faced the board of education on a regular basis. The board was four inches wide and three feet long. I would feel the wrath of my mother for every little thing. If I broke a dish, swore, came home late or didn’t get 70 percent on a test,” he said.

According to Dahl, the cross country information sessions for survivors need to focus more the historical context of how the lawsuit came to be.

“There should be mention of the (Justice Edward) Belobaba lawsuit, how it originated and the process that it went through – the hopes and the fact that it was almost dismissed several times,” Dahl said.

Dahl said while no amount of money can take back his loss of culture and identity, he is satisfied that a healing foundation is attached to the settlement to support survivors in their own healing journey.

“Nobody comes to us now and says you are still part of the family, part of the community, why don’t you come forward and sing with us? Why don’t you come forward and drum with us? Nobody invites us to do that. I think that is part of the missing link for us for healing,” he said.

(The Dahl household in Red Lake, Ontario. Photo courtesy: Roy Dahl)

Dahl has been waiting many years for what he values most – an apology from the federal government.

“It’s about Canada saying sorry to you, saying ‘we are sorry we tore your families apart all because we thought you weren’t good parents, because we thought you weren’t good people,’ for Canada to step forward,” he said.

According to Collectiva, the claims administer – any First Nation or Inuit person who was adopted or made a permanent ward and was placed in the care of non-Indigenous foster or adoptive parents in Canada between 1951 and 1991, is eligible for compensation.

Forms must be completed and submitted by August 30, 2019.