The Hope for Wellness Helpline is available 24/7 at 1-855-242-3310.

A gust of wind drifts through the prairie grass and into the city of Edmonton. A peaceful setting until you learn the history of the area.

The rural city limits have long been an informal resting ground in Alberta’s capital city, where dozens of missing women’s remains have been located, many of whom worked in the sex industry. Thirty-seven women have been found in rural areas outside of the city.

The rural outskirts of the city have been referred to as the “killing fields” by sex workers and advocates alike for decades.

Sites that are marked by rolling acres of farmlands and gravel roads are desolate locations that are often overlooked as the final resting place for murdered women. These places are where a disturbing number of bodies have been found over the last 50 years or more.

“There’s been situations where our women have been found piece by piece or not found at all,” says Métis social worker Felicia Ricard.

An APTN investigation identified 215 missing and murdered women in Edmonton since 1971.

Of those identified, 22 per cent worked in the sex industry. More than half of the sex workers were Indigenous people.

Newspaper articles, incomplete police databases and public family statements were used to identify the women.

The Métis social worker does intake and therapy sessions on top of her already busy schedule. She runs an outreach program in the evenings for street-level sex workers.

APTN Investigates spent a week on the ground with Ricard and spoke to advocates to gain a better understanding of the sex industry.

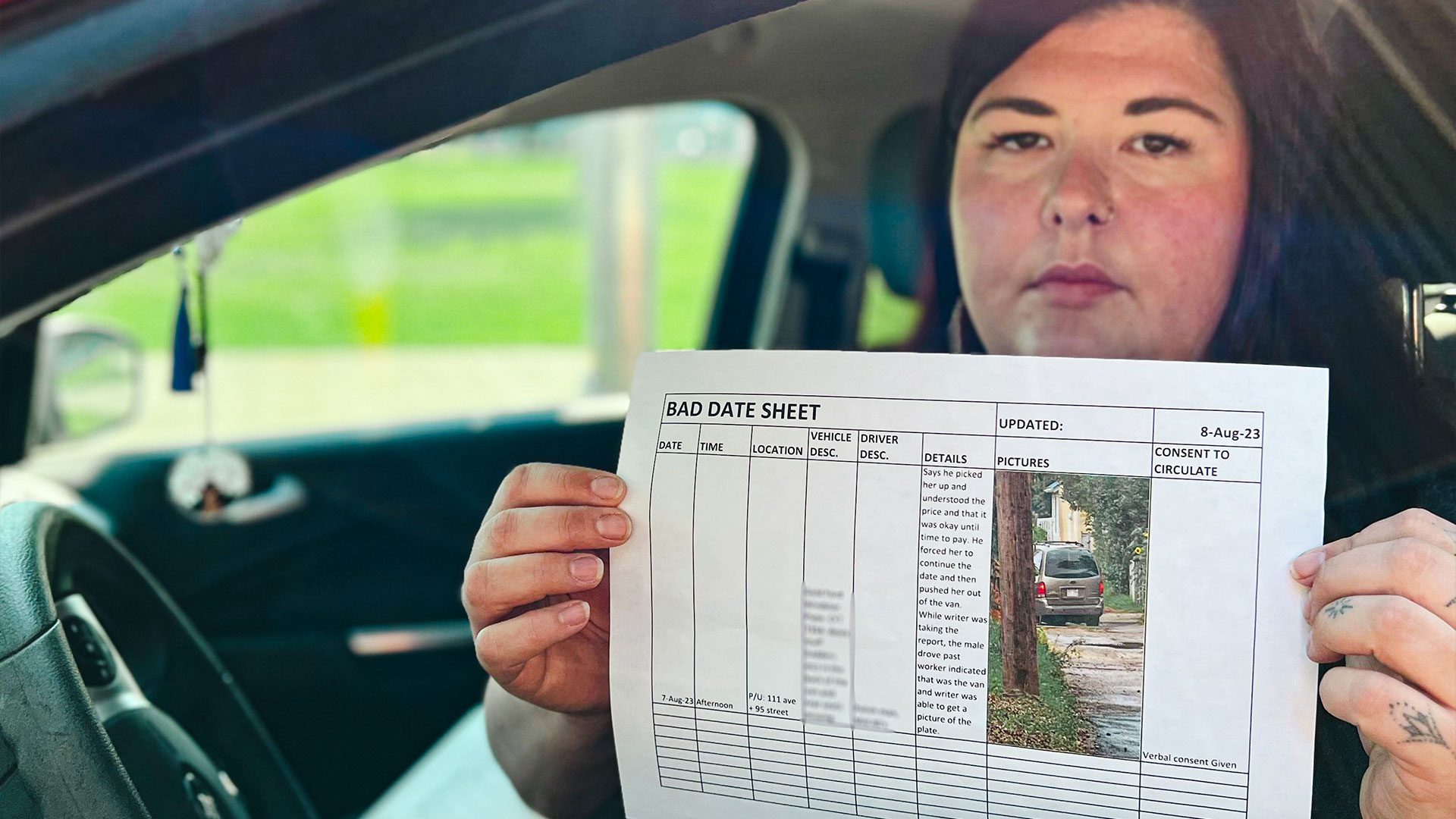

“Here’s a bad date sheet for you, make sure you’re staying safe,” she says from the driver’s seat of her van, identifiable by the “Auntiesaurus” sticker on the back window.

Ricard offers snacks, safe sex supplies and a listening ear to people she encounters in her work.

The outreach program was designed with safety in mind.

She collects up-to-date information on sex workers’ appearance and their last known whereabouts in the event they are murdered or go missing.

Ricard also routinely hands out “bad date” lists to notify sex workers of violent clients. The list includes a description of the client, their vehicle and information about the violent encounter.

“Many (sex workers) have said that every car that they get into, they sell a piece of their soul when they get into that car,” said Ricard.

The RCMP’s Project Kare unit started doing the same work Ricard does after a number of women’s remains were found just outside of Edmonton in the early 2000s.

The unit worked to identify dangerous clients, collected current photos of sex workers and with their consent, RCMP obtained DNA samples.

The unit dissolved several years ago, leaving much of the work to non-profits and grassroots organizations to undertake.

Ricard said the work is essential and that more resources need to be allocated to keeping sex workers safe.

“When you don’t see them for a while you start wondering,” she said. “But there’s also this side of you that’s like, I don’t want to see them out here because that means that they’re working, that means that they’re struggling.”

One street in Edmonton, 118th Ave., is on her nightly route. The stretch of road is infamously known as the heart of the city’s sex industry.

It’s also the last known whereabouts of several sex workers and Indigenous women who have seemingly vanished.

Liz Callingbull-Taylor worked the same streets that Ricard patrols.

“You do learn very quickly what you can or cannot do out here and if (the girls) say, ‘don’t go in it’, you don’t,” she said, referring to a client’s car.

“Some of them didn’t listen and we never saw them again.”

Callingbull-Taylor said the trauma and violence she endured on the streets was difficult and she didn’t want to leave her children without their mother.

“My rock bottom to me was, what am I more afraid of? Dying or change?” she said.

She made the difficult decision to leave the sex industry more than a decade ago and is now focused on healing her childhood traumas.

The sex industry has dramatically evolved over the decades and is no longer only found on the streets.

Webcamming, escorting and erotic indoor massages are just a few examples that fall under the umbrella term of sex work.

Known only by their working name, SinoMin entered the sex industry just a few years ago.

They started as a dancer at a nightclub, but now offer erotic massages to clients.

“I felt kind of like this weight on me when I first started dancing and then I heard what (my coworker) was telling me was, it’s a business, this is your business, this is income, this is you working,” said SinoMin.

Sinomin said that while some sex workers may experience feelings of guilt or shame, others do not and instead find the work empowering.

“When I realized that it’s all up to me and I get to choose everything and that made me feel very powerful,” they said.

That same element of empowerment is something Callingbull-Taylor echoed.

SinoMin said it’s important to recognize the differences between sex work and sex trafficking and that not all sex workers are being exploited.

They said there are dangers to be aware of when working in the industry, but the advocate said it could be better regulated and made safer for sex workers if their work was decriminalized.

In September, the Ontario Superior Court ruled that Canada’s laws on sex work are constitutional.

Justice Robert Goldstein concluded that sections in the Criminal Code do not prevent sex workers from taking safety measures, using services of non-exploitative third parties or seeking police assistance.

The decision left many sex workers and advocates disappointed.

“You never know who’s going to walk through that door,” said SinoMin. “You really have to just go with a couple of texts that you’ve exchanged and be like ‘Okay come in’.”

The individuals APTN spoke with said the decriminalization of sex work would mean recognizing sex workers’ right to autonomy and self-determination.

Additionally, it would include the removal of laws that prevent the selling, buying and procurement of sex.

“There’s the thought of, ‘well we’re selling our bodies’, when in the same vein, working for minimum wage or whatnot, it can be also be seen as selling your body, but working for a corporation,” said SinoMin.