The Sisson mine in New Brunswick is one step closer to reality, but Wolastoqey leaders and grassroots people say they still withhold consent for the controversial project.

Late last month, the Trudeau government cabinet quietly approved the destruction of two brooks at the proposed project site to make way for a tailings pond.

In response, Wolastoqey First Nation leaders issued a joint statement condemning the move, saying they weren’t consulted on the matter.

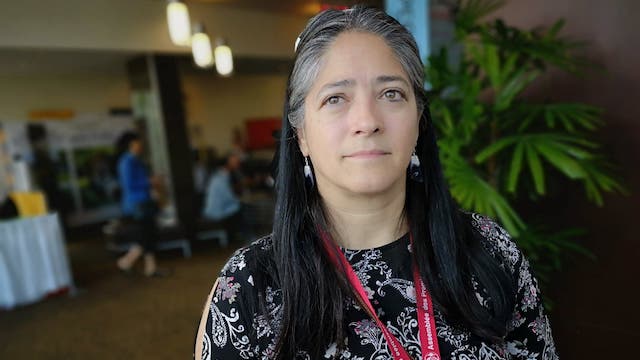

On Wednesday, Madawaska First Nation Chief Patricia Bernard told APTN News five of six Wolastoqey chiefs remain opposed to the project, and that despite signing “accommodations” agreements in 2017, they still have not consented to the project.

“Signing a consultation agreement is not consent. It just means that we went through the consultation and accommodation process. So by going through that process we signed an agreement saying we did. But at no point in the agreement does it say we consent,” Bernard said at the Assembly of First Nations’ Annual General Assembly in Fredericton.

On Tuesday New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs addressed the AFN delegation and afterward told reporters the crown’s duty to consult “is not well defined.”

The Conservative leader, whose government inherited the project from the Liberals, said he would like a better understanding of duty to consult around resource projects so the province and First Nations can work together while giving investors certainty.

New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs says he’s looking for clarity around the duty to consult First Nations in the province. Photo: Justin Brake/APTN.

“At the end of the day if we want investment in our province, and if we’re all saying we want our economy to grow, and we all want to have the funds generated in order to look after the education and the systems that need to be upgraded — all of these issues that are real — we have to know what the process is so we know when we’re finished,” he said.

“Because investors will leave. But in Canada we’ve seen a lot of investors leave for a lot of different reasons, so we need to figure this one out because it’s important to the future of our country.”

Federal Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett met with Wolastoqey leaders Tuesday in Fredericton and said they were clear in their position on the mine.

Bennett told reporters that the proposed mine “has many, many more steps ahead of it” before potentially receiving final approval.

She also reiterated Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s statement that when it comes to provinces and territories dealing with Indigenous groups, “Section 35 rights are not optional.”

“The path of reconciliation and listening is a journey, not a destination,” she added.

Asked about recent concerns from Wolastoqey and Mi’kmaq leaders about the province’s decision to lift a moratorium on fracking in New Brunswick, Bellegarde said there should be no confusion around how to respect Indigenous rights.

“You need to move beyond duty to consult and accommodate and use free, prior and informed consent,” he said, referencing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. “If you want a real stable economy, you want an economy that’s ripe for investment, everybody’s got to know what the rules are.”

Higgs said it’s “a well known fact” part of New Brunswick is on unceded Wolatoqey territory, but admitted the government and First Nations “need to work through what that means, and how do we go forward together.”

After signing the accommodation agreements with the province in 2017, Wolastoqey leaders said they were pressured by the Liberal government, who they claim threatened to not renew a taxation agreement that provides desperately needed revenues for the communities.

Madawaska First Nation Chief Patricia Bernard says five of the six Wolastoqey First Nations have not consented to the Sisson mine. Photo: Justin Brake/APTN.

The accommodation agreements came with a $3 million signing bonus and a promise of 9.8 per cent of revenues if the mine comes to fruition.

But the money isn’t worth what could be lost, Bernard said Wednesday.

“I know my community is not in support of the mine. And it isn’t to try and prevent economic growth — we have to prioritize. Is the economic benefit more important than the environment? And whatever happens to the environment, can that be repaired if there’s any damage? Clearly there’s going to be damage. When you look at the scope of a mine it’s a huge impact. There will be damage to the land, to the wildlife, to the water systems.

“I don’t think the cost to the environment outweighs the economic benefit.”

Grand Chief Ron Tremblay, leader of the traditional Wolastoqey Grand Council, says a dollar value can’t be placed on an open pit mine’s cost to the land, and through the land to the people.

He says a dam breach at the tailings pond, or other pollution to the brooks in the area could devastate local rivers, including the Wolastoq River — also known as the St. John River — which Wolastoqiyik derive their name and identity from after living along its shores for thousands of years.

“We are the Wolastoqiyik, which means we are the people who have a responsibility to that river called the Wolastoq, the beautiful and bountiful river,” he told APTN Monday during an interview deep in the woods near the proposed mine site about 100 kilometres north of Fredericton.

“Our main responsibility is to protect water, especially that river. Sisson mine connects to the Nashwaak River, which eventually flows down to the Wolastoq, down to our main river,” he explained.

The Wolastoqey Grand Council represents the Wolastoqiyik traditional governance system and is comprised of grassroots people. Tremblay takes his direction from the grandmothers.

One of those grandmothers, Ramona Nicholas, and Tremblay guided APTN to the proposed Sisson site, where a camp was established a few years ago and now has two professionally built homes, a trailer and garden.

Ramona Nicholas, a Wolastoqey Grandmother and member of the Wolastoqey Grand Council, says the area a B.C.-based mining company wants to develop an open pit mine is important to her people for ceremonial and other purposes. Photo: Justin Brake/APTN.

A few kilometres up a logging road from the camp, Nicholas visits a spiritual site that she and other grandmothers chose a few years ago, where they’ve built a long house and conducted numerous ceremonies.

“I thought it was important for us to reconnect back by doing ceremony, and that’s for me why establishing this area to have a sweat lodge, to have a long house, to have that area so we can have our ceremonies out here so that we can connect not only to the land but the ancestors that are here as well,” she explained.

A trained archaeologist with experience on resource development projects, Nicholas said she chose the ceremony site because it’s adjacent to where archaeologists working for the province found a spear point dated more than 8,000 years old.

“And this is the area also where the ore body is, so protecting this and making sure that we protect this area is kind of just as important as protecting all the rest of it,” she said.

Nicholas, presently a graduate student at University of New Brunswick, said she’s working with another student to develop a land based learning program for her people.

Bernard and Tremblay both maintain Wolastoqey land has never been ceded to the province or to Canada.

“This is unceded territory and it belongs to the people. It doesn’t belong to the leaders, it belongs to the Wolastoqiyik people,” Bernard said.

In the bush, Tremblay explained that through the Peace and Friendship Treaties signed with the crown in the early 18th century, “there was not one speck of Earth, one drop of water, or one breath of air that was surrendered during those times.”

He said the treaties are “protected under [Canada’s] constitution,” and that “they’re still a living document and still exist as a legal document.”

Tremblay said the Wolastoqiyik inherent and collective rights “are connected to this land,” and that governments have “neglected to talk to the people and to the traditional leadership…because they know that our real connection and the real ownership belongs to the peoples of this land.”

He and Nicholas both said those making decisions about the fate of their land have never stepped foot on it.

“We have these higher-ups in the federal government making decisions on land that they know nothing about,” said Nicholas.

Tremblay extended an invitation to the politicians.

“I want to invite them here, to walk through this beautiful forest and visit those waterways that they’re planning on damaging and polluting,” he said.

“This is life. This is what all living species rely on. The trees are our lungs. And those waterways are our ways to quench our thirst, and so on.

“So if you take your shoes off and come out to the land and put your feet on this land, and put your feet in the water — that’s life. That’s life of our peoples.”

Back at the camp, 33-year-old Nick Polchies of Woodstock First Nation—the only Wolastoqey community to sign an agreement with the company that hopes to build the mine—has been living on the land for the past two years.

Nick Polchies of Woodstock First Nation says he will do whatever he can to stop the mine. Photo: Justin Brake/APTN.

He said he has no plans to leave and will defend his people’s territory if necessary.

“If they try to bring in equipment I will dig out roads, I will stop them, I will get in their way, I will make it a problem for them,” he said.

“If I have to I will be a driving force to stop them.”

Nicholas and Polchies said they believes if construction begins in the area, citizens of the Wolastoqiyik Nation and allies will show up.

APTN reached out to Northcliffe Resources President and CEO Christopher Zahovskis but did not receive a response by deadline.

In a July 10 news release Zahovskis said that the recent cabinet decision on the tailings pond “represents an important milestone toward project development.”