Clarence Iron calls the Winnipeg Jets vs Chicago Blackhawks game Jan. 19. Jesse Andrushko/APTN

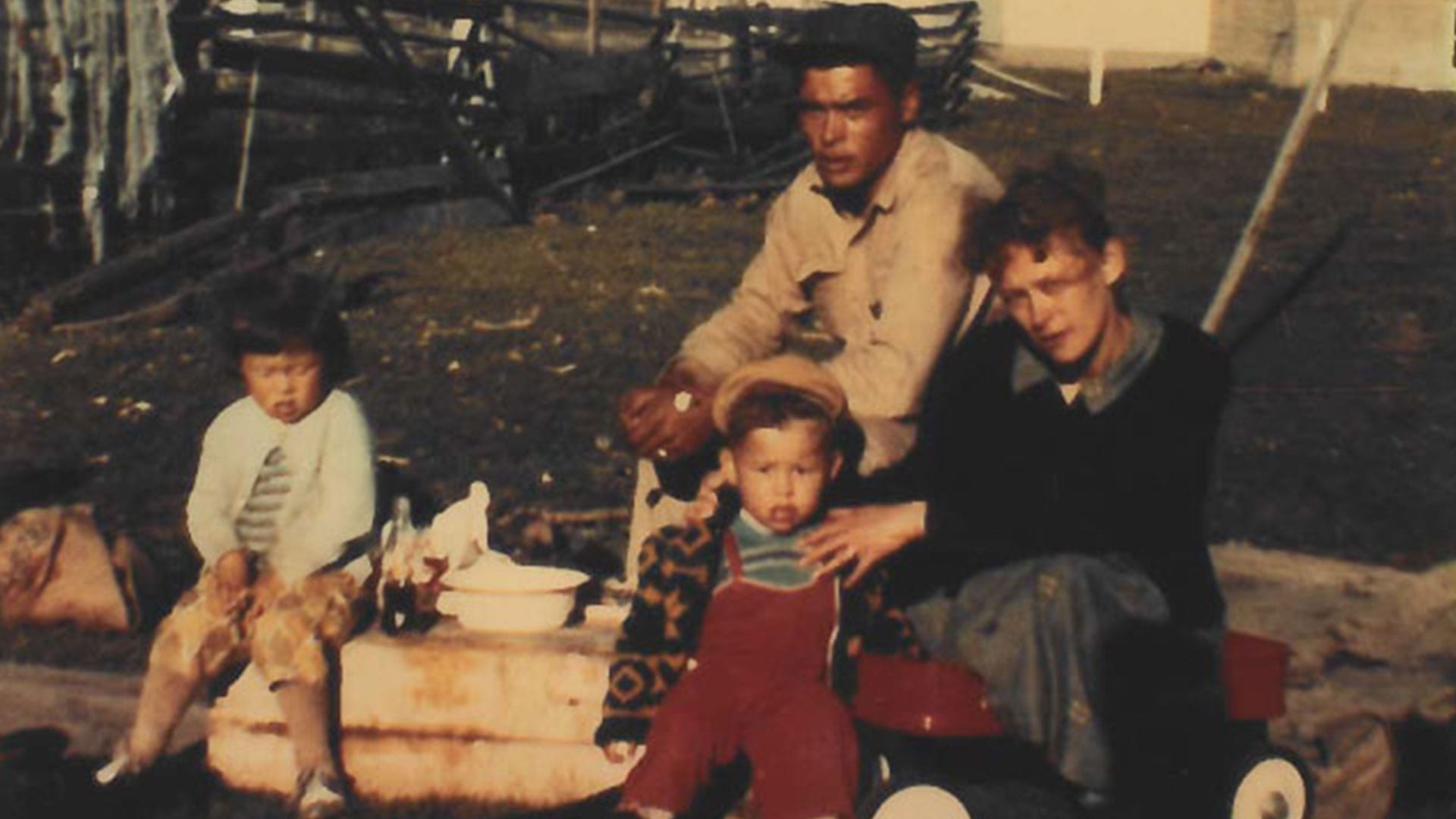

When Clarence Iron was a tsiboy – that’s small boy in Plains Cree – he used to listen to hockey games on the radio.

There were only six National Hockey League (NHL) teams back then and he was stuck rooting for the Toronto Maple Leafs.

“All my friends picked a team and I was the last,” said Iron, a sports radio broadcaster who grew up in Saskatchewan’s Canoe Lake Cree Nation.

“Little did I know the last time they won the Stanley Cup was 1967.”

Iron had the same dream as many 12-year-olds across Canada – maybe one day he’d play in the bigs and make it to the NHL.

But then his father died and Clarence was apprehended and sent to one of Canada’s notorious Indian residential schools.

He was ordered to forget everything he was – a First Nations boy who loved his family and culture – and conform to the colonial immersion program that aimed “to kill the Indian in the child.”

The hundreds of schools across the country funded by the federal government and run by church groups left a legacy of pain and destruction from which many First Nations, Métis and Inuit children never recovered.

But Iron survived with his language intact to revisit his dream of, well, not playing but doing the play-by-play for the big leagues.

After decades calling hockey games on radio in Saskatchewan, Iron is now part of the on-air team of Rogers Hometown Hockey in Cree on APTN with Earl Wood, John Chabot and Jason Chamakese.

The Indigenous commentators are part of a partnership to broadcast more NHL games in Plains Cree over the course of the next three seasons after doing so well in their inaugural broadcast on APTN last year.

“People are excited. Even non-Aboriginal people are listening,” said Iron, who spoke to APTN while calling the Winnipeg Jets versus Chicago Blackhawks game Sunday night.

“It’s a high number (of viewers) and they tell me, ‘Clarence, I didn’t know what you were saying but we did watch the whole game because you were exciting.’”

Watch Clarence in action here:

Iron doesn’t have a “colour man” to spell him off in the broadcast booth but he does have a spirit guide.

“I want to give praise to my God. That’s the Number 1 thing that gives me the confidence,” the 58-year-old said in an interview.

He said he would still be searching for a place and a purpose if he didn’t leave drugs, alcohol and violence behind. And get off the street.

“I don’t think this opportunity would have happened if I didn’t straighten my life out. I was angry – angry that my dad was murdered (and it wasn’t investigated).”

After residential school, Iron was sent to the former Charles Camsell Hospital in Alberta as a tuberculosis patient. The substandard care given Indigenous patients in TB hospitals is now the subject of a class-action lawsuit.

After stints in the oil patch and other workplaces, he said he served time in jail for assault. Then he said his lawyer botched his claim for financial compensation from the federal government for residential school survivors.

“A lot of things didn’t go right. But I’m putting that behind me,” he said, noting if he can hang onto his language and heal others can, too.

“My thinking has changed. I’m not scared no more.”