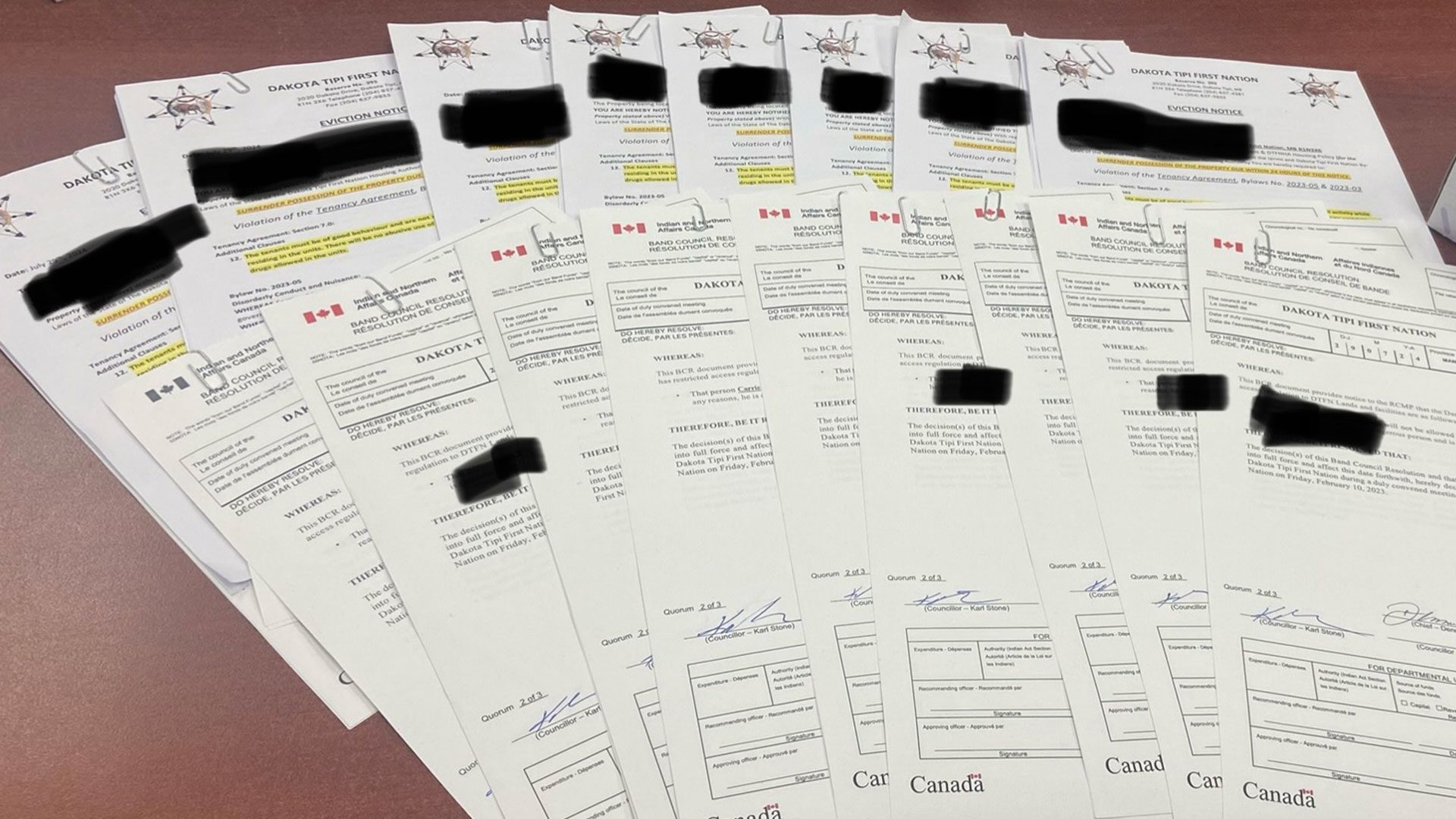

At the Dakota Tipi First Nation band office, nine eviction notices are sprawled out on a boardroom table.

Each notice is addressed to a band member accused of using or selling drugs.

They’ll be given 24 hours to leave their dwelling before the RCMP force them out.

The band council says it’s a last resort after doing everything it can to combat the drug crisis.

“We have to struggle for our people to survive, for our young people. It’s tough having to bury a lot of young people, and we have another funeral to go,” Dakota Tipi Chief Dennis Pashe said. “We’re in a war. We’re in a war against drugs, and we’re losing that war.”

In Dakota Tipi, a small community located 90 km west of Winnipeg, virtually everyone has lost a relative to an overdose or drug-related violence.

In a news release published Wednesday, Portage La Prairie RCMP said a 28-year-old female from the community was abducted and assaulted by two women on July 25th.

On Sunday, Pashe’s nephew, 36-year-old Kennedy Elk, was murdered in Winnipeg.

Back in February, the community declared a state of emergency as a call for help to combat the drug trade.

Now, they’re calling on the federal and provincial governments to take action and provide urgent resources.

“These health service agencies, they just don’t seem to be getting it, that our people are dying,” Chief Pashe said. “It’s a crisis. We’re trying our best to deal with it and help people but at the same time the resources aren’t there to do it.”

Out of options

As the crisis intensifies, chief and council said they can’t wait any longer. They’re now serving eviction notices to band members caught using or selling drugs.

Braden Pashe, who leads the community’s safety officer program, said the team has been using a combination of community reports, photos and video surveillance as evidence of people using or dealing drugs.

Dakota Tipi finance minister, Miranda Smoke, said band members caught using drugs are first given a written warning and connected to treatment services.

If they continue using, they are taken off cheque-based social assistance and moved to a food voucher program to deter them from using funds to purchase drugs.

As a last resort, they face eviction and banishment from the community.

“If they’re resistant to going to treatment or they flat out state that, ‘No, I don’t need help, I’m fine’ and they’re in denial then this would be our last draw,” Smoke said.

Looking to the land for healing

A few kilometres outside the band office, Counc. Karl Stone gives a tour of a former bed and breakfast the band currently rents.

They hope to transform it into a treatment centre but require more funding to make that a reality.

Stone ties disconnection from traditional lands and culture to people turning to drugs to cope with trauma.

“The trauma that our people had to endure from the loss of land and the loss of use to our lands and our medicine, and all that being stripped and taken away from our people, our people have had to suffer that,” Stone said.

He believes a treatment centre could regenerate those connections, helping people heal.

“The land is something that could be beneficial for our peoples’ healing, you know, so that they could get the help that they need to get off the drugs that they’re on,” he said.

Back in November, the band council demolished a known drug house in the community.

Justice coordinator Braden Pashe said the land will soon be home to multi-family housing.

“Like all First Nations, we lack housing and so this will benefit the community lots by having a five-plex and giving these young people a chance to be homeowners,” Pashe said.

Action over apologies

In June and July respectively, the community received apologies from the neighbouring town, Portage La Prairie, and the federal government for past wrongs.

Pashe said action – not apologies – will help the community heal.

“It’s depressing in a sense, you know, when we all know what the issue is and we’ve been advocating (for) that issue but it’s falling on deaf ears,” he said.

With additional support, the community hopes to hire more healthcare professionals, build a treatment centre and expand its safety officer program to curb the drug crisis.