Sacha Raven Bob died suicide Sept. 10, 2014, but records show Weechi was aware of issues with the child protection team, including her worker. Facebook photo

Weechi-it-te-win Family Services knew 75 days before Sacha Raven Bob took her life that there were problems within the child protection team at Big Island First Nation.

The team was behind in their case notes.

Weechi also flagged Sacha’s worker for training.

She needed help maintaining files.

There was another problem.

Weechi wasn’t keeping track of the files.

“There are no regular formal case reviews to keep this worker aware of the progress or regression of protection cases,” wrote Jackie Jourdain-Adams, in a June 27, 2014 internal report obtained by APTN News.

Jourdain-Adams also wanted to begin case management training in September despite supervising the Big Island team since December 2011.

The report also says an audit of child in care files was to happen before 12-year-old Sacha took her life on Sept. 10, 2014 in the closet of her bedroom in Onigaming First Nation.

But it’s not clear what, if anything, happened.

The leaked internal report provides the first glimpse into Weechi before Sacha passed.

The report “glosses over serious departures from the standards” for children in care according to Dr. Kim Snow, a leading child welfare expert who reviewed the report for APTN.

“Including the significant finding that recordings were not current,” said Snow, who is a professor at Ryerson University.

“They were well aware of these problems before Sasha Bob died.”

Five months after her death everyone knew, including the province and chief coroner.

Her death sparked what’s known as an internal death review.

An audit of her protection file found key documents were missing from her file. That includes plans of care totalling seven years.

Mandatory visits didn’t happen, or were late.

When Sacha began showing signs of sexualized behaviours beginning at the age of four there were no records to show it was addressed.

The same thing happened when she was later sexually abused in her short life.

The list goes on – 91 pages of it.

In depth: Death by Neglect: Sacha Raven Bob died alone and Weechi failed to save her

But Big Island wasn’t the only First Nation under Weechi that was struggling at this time.

Weechi, based in Fort Frances, Ont., oversees 10 First Nations and documents show half were “functioning low”.

One was described as “hit or miss”.

And another as “chaotic.”

“These reports document known concerns, including child welfare workers not answering their phones, children in care not having face to face visits with their workers and a general lack of case review throughout the agency,” said Snow, looking at Weechi collectively.

“These reports suggest that this is a child welfare agency struggling to meet its child protection mandate and not meeting its fiduciary responsibilities to the children in their care.”

This was the state of Weechi in 2014.

Concerns about Weechi meeting its fiduciary responsibilities continue to this day according to information APTN obtained over the last eight months.

That includes interviews with children in care, caregivers and former employees.

There was a common term that everyone knew and many had done.

“I can tell you I am ashamed to say I have done it,” said Sarah Laurich, the executive director of the Atikokan Native Friendship Centre.

“It’s a horrible position to be put in as a caregiver.”

Laurich is talking about “backdating”.

Workers have a timeline to follow to say they’ve seen a child, or caregiver and parents. Everything is done by dates, but workers are known to miss those dates for such things as plans of care and other key documents that the government requires be done by certain dates to ensure a minimum standard of care.

Laurich said in 2019 she was asked to sign three documents with varying dates for plans of care that hadn’t been done for the child in her home.

“I knew exactly what they were asking me to do. I didn’t want to do anything to jeopardize that placement. As a caregiver it’s frightening when a worker comes into your home and tells you to do that,” she said, adding caregivers fear the child will be removed.

That wasn’t the only time.

“Not only was I asked to backdate, but the plan of care was missing,” said Laurich.

That means she just given the pages to sign and date.

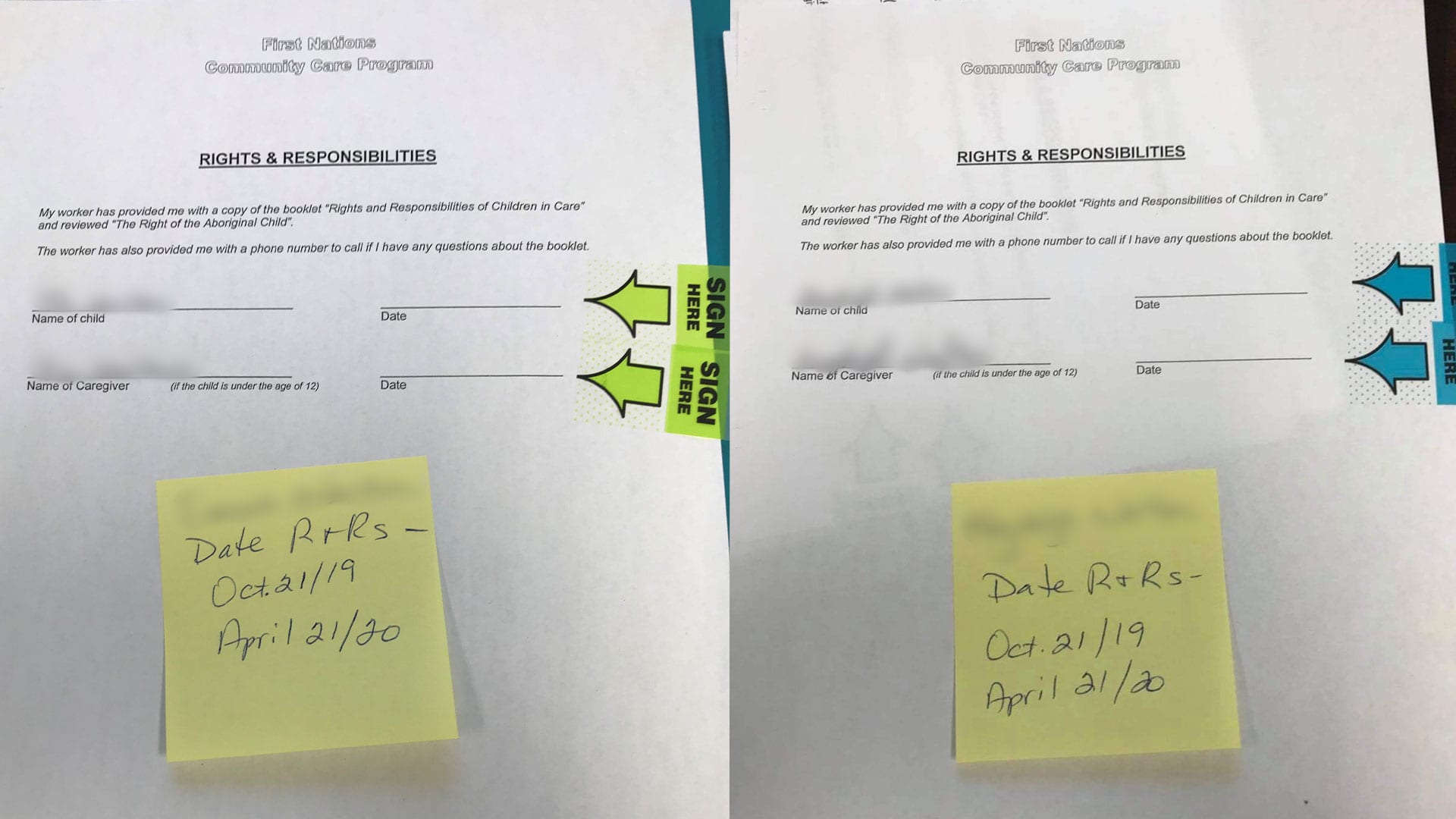

APTN found a more recent case of backdating when a long-time Weechi caregiver said a worker dropped off some forms at the caregiver’s office in early October.

They there pamphlets to remind her two teenaged foster daughters of their rights in care.

The worker was also supposed to go over the document with the youths to ensure they know their rights and she’s supposed to do it every six months.

But Priscilla Jourdain, who works with the Lac La Croix First Nation child protection team, was a year late when she dropped the documents off.

On each paper was a Post-it note of the dates to she wanted the girls to print and sign, according to the caregiver and both teenagers.

“I said it’s up to you if you want to put that wrong date on there, but you know your worker didn’t come,” said the caregiver, who the girls call ‘mom’ after 12 years.

The girls signed but didn’t date the documents as asked.

“I feel like I shouldn’t have to,” said one of the sisters. “They are not coming to my house and talking to me. I don’t care what it’s for.”

As it happens, the ministry of children, community and social services pulled the girls file in its annual audit in October, according to the caregiver.

“This is wicked fresh,” she said. “They pulled my file, so I told the ministry exactly what’s been going on because I am tired of these kids not being seen by their worker.”

She said it’s dangerous that worker doesn’t show up on a timely basis, as required by the Child, Youth and Family Services Act.

“Because you don’t know what’s going on in that home. You are supposed to be making a relationship with the children. They should know you and they don’t,” said the caregiver.

Over the 30 years she’s been a caregiver for several Weechi communities and APTN asked her how often was she’s been asked to backdate a plan of care.

“How many times was it on time, that may be easier to ask,” she replied.

How many times?

“Hardly ever,” she said.

In 30 years?

“Hardly ever.”

She said there was another plan of care she was recently asked to backdate and it involved a child that had been in her care for a year.

The placement broke down this past summer, which APTN first wrote about in November. It involved a runaway youth in Barrie, Ont.

The youth’s worker was Shannon Stone up until June 1 when Stone quit her job at the Rainy River First Nations child protection team due to internal abuse from a band councillor there.

The caregiver said after Stone quit she received no support for the high-risk youth and the placement fell apart on July 31.

A couple months later the caregiver said she got a call from Anges Grover, the alternative care coordinator at Rainy River asking her to backdate a plan of care.

Grover apparently said Stone didn’t do one, according to the caregiver.

“I know I did a plan of care with Shannon,” said the caregiver. “I knew I did it.”

She said that’s the only reason she agreed to do it.

“I signed it because I knew I did it with Shannon,” said the caregiver.

After the story came out Rainy River focused on Stone and removed a child from her care.

Stone was one several sources the story, but suddenly, after having the youth in her home since January, she was told there was no longer an agreement to keep the youth there. They also said her home had been closed, when it in fact had not.

The youth was removed anyways.

Related: High-risk youth abruptly removed from Weechi foster home despite counsellor’s objection

She spent time in two different foster homes before being returned to Stone two weeks later with the help of lawyer Marco Frangione.

APTN also continued to follow that story.

APTN was told there’s a certain time of a year when workers go looking for documents or to get signatures.

Every fall the ministry audits a small number of files, including interviewing caregivers and children, for all 10 nations.

In fact, this is such a hectic time of the year the workers complained about it in the report on Sacha’s death investigation.

“Too much last minute clean up before audits and too much work to clean up files falls on WFS staff,” was one of the complaints.

APTN had several experts, ranging from former workers to lawyers, provide their opinion on what that line means.

Each was provided a screenshot of the text and asked: What does this line mean to you?

“Clean up means they try to present that good work was done when it never was,” said Frangione.

“Backdating is one of the terms that came to mind. It’s horrifying that this is somehow seen as an acceptable practice, but I am not entirely shocked,” said Carina Chan, a child protection lawyer in Toronto.

“It sounds like files are often not kept organized and up-to-date and the workers have to scramble to rectify this before an audit.”

Chan also wondered if cases notes were falling behind.

Former workers said it also shows Weechi was involved in the clean up to pass ministry audits.

“It means that Weechi workers are having to call dentists, doctors, optometrists to find the missing forms. When they shouldn’t be on the front lines with children in care. That responsibility falls on the community workers or it’s supposed to and doing outstanding plan of cares,” said Kathy Foy, who used to work for the Couchiching First Nation child protection team up until 2018.

“It’s backdating. We all used it.”

The ministry pulls the files at random said Foy and then tells Weechi which files it will be auditing before meeting with anyone.

That’s when the panic sets in for workers.

Foy also said a reason why files are not always up to date is because workers are crisis-driven. It’s one thing after another and they need more support.

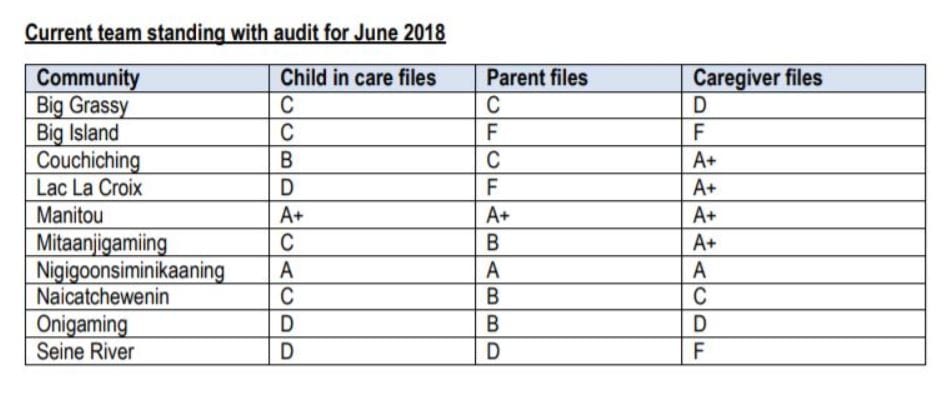

Weechi also audits their files and the results suggest there is good reasons workers panic when the ministry comes calling.

Below is a screenshot of a June 2018 audit found in Weechi’s 2018 annual report.

Big Island had got failing grades in the parent and caregiver files.

It’s best was a “C” for the state of its child in care files.

This is nearly four years after Sacha died.

Failing grades.

“The items that make up the grade represent a minimum standard of care. Child in care files that receive grades that are D or C, should raise alarm bells at the Ministry, and they should require the agency to immediately remedy these files and develop an action plan to ensure that they maintain standards,” said Dr. Kim Snow.

“These are the most vulnerable children, the province has assumed guardianship, and there is an enhanced duty of care owed to them.”

It’s been difficult to find out what the ministry has done with Weechi.

APTN asked the ministry for evidence, but it didn’t directly respond to our questions.

Jill Dunlop, who is the associate minister in charge of child protection, refused to sit down for an on-camera interview with APTN, despite being given a two-month window.

Her chief of staff, Alexandra Blair, never responded to messages from APTN.

It’s also unclear what the ministry has done since APTN first reported the story of a 15-year-old boy with rare condition known as Sprengel’s deformity.

Medical records show the First Nations boy in northwestern Ontario missed years of medical checkups, including a referral to a specialist, while in the care of Weechi.

It may be too late to treat the rare congenital disorder where one shoulder blade is larger than the other.

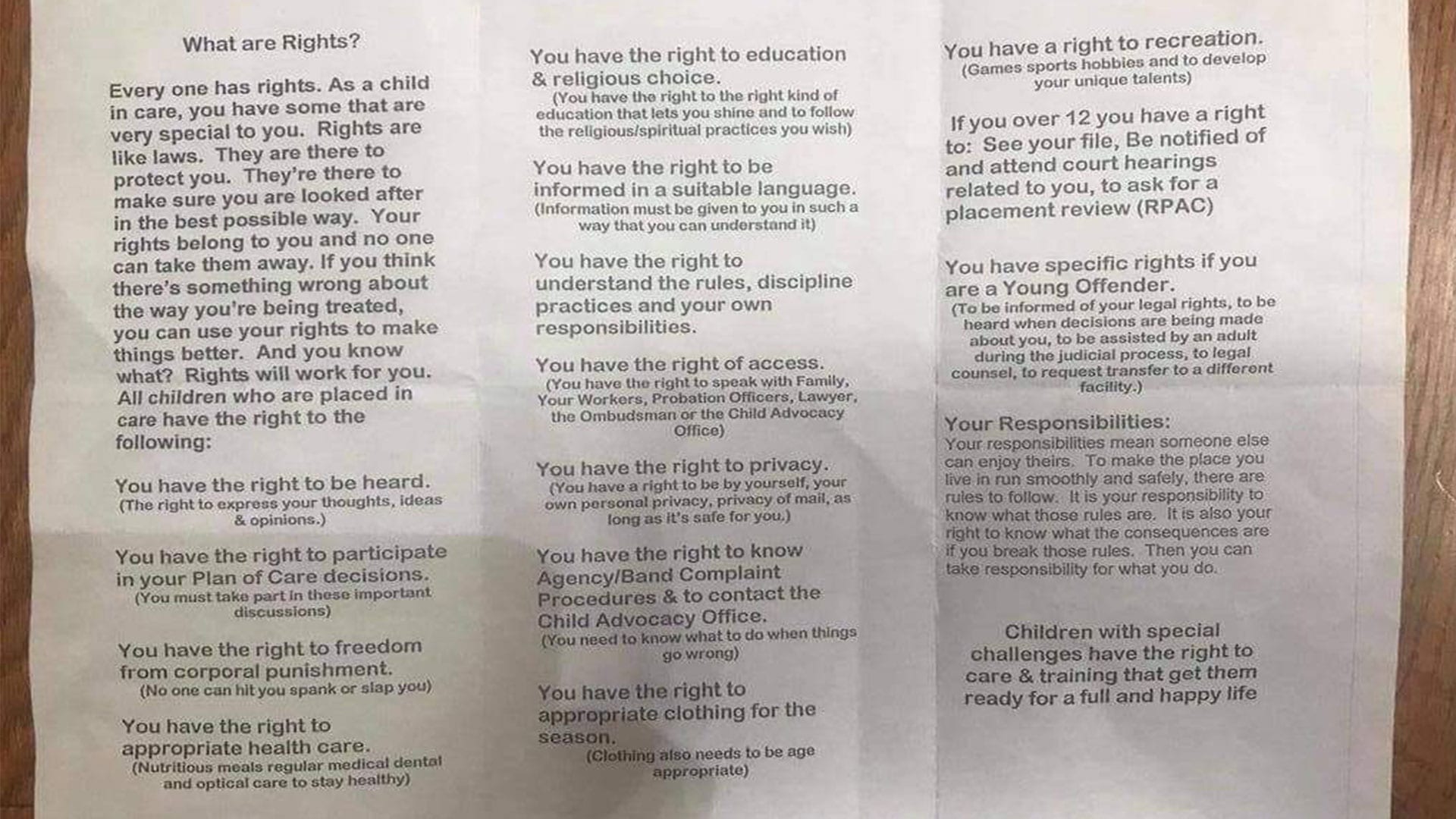

Soon after that story the youth got a new worker and was provided a pamphlet on his rights in care.

APTN determined the pamphlet was at least 13 years old based on a number of factors, including interviews with experts.

Irwin Elman pointed out the pamphlet refers to the child advocacy office, which was around prior to the provincial child advocate office beginning in 2007, two distinct things.

Premier Doug Ford closed that office, too, in 2019.

Elman was the first and last provincial advocate.

The pamphlet also uses terms older terms like “young offender” and “special challenges”.

One former, and long-time, Weechi caregiver remembered the pamphlets. She also has worked in a printing shop for more than two decades in Fort Frances.

She took a look at it for APTN.

“Old!” said Roz Calder, who knew Sacha. “They are at least 15-plus years old, if not more.”

APTN wrote the youth’s worker asking why she was handing out dated rights. Soon after the boy got an updated pamphlet.

The same old pamphlet was given to the teenaged sisters, who refused to backdate it.

APTN learned Rainy River also uses the same pamphlet.

Following the youth’s story, APTN learned of a mother who had been fighting to get her last daughter out of care.

The mother demanded to see a copy of the customary care agreement that was keeping her daughter in care.

In fact, she challenged if one existed.

But she kept being told by a the supervisor of the Couchiching team there was an agreement during a recorded phone call.

That supervisor told her five times there was one.

What she didn’t say is the agreement had expired two years prior.

The supervisor’s name was Jackie Lizotte, formally known as Jackie Jourdain-Adams – the same person mentioned at the beginning of this story.

Three days after that call the mother had her daughter back because Weechi closed its file.

Everyone named in this story was given an opportunity to respond and did not, including Weechi’s executive director, Laurie Rose.

Rose is the legal guardian for all kids in care under Weechi.

She was Sacha’s too.