The University of Manitoba says it wants to return hundreds of Indigenous ancestral remains, belongings and artifacts in its possession to their rightful First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities.

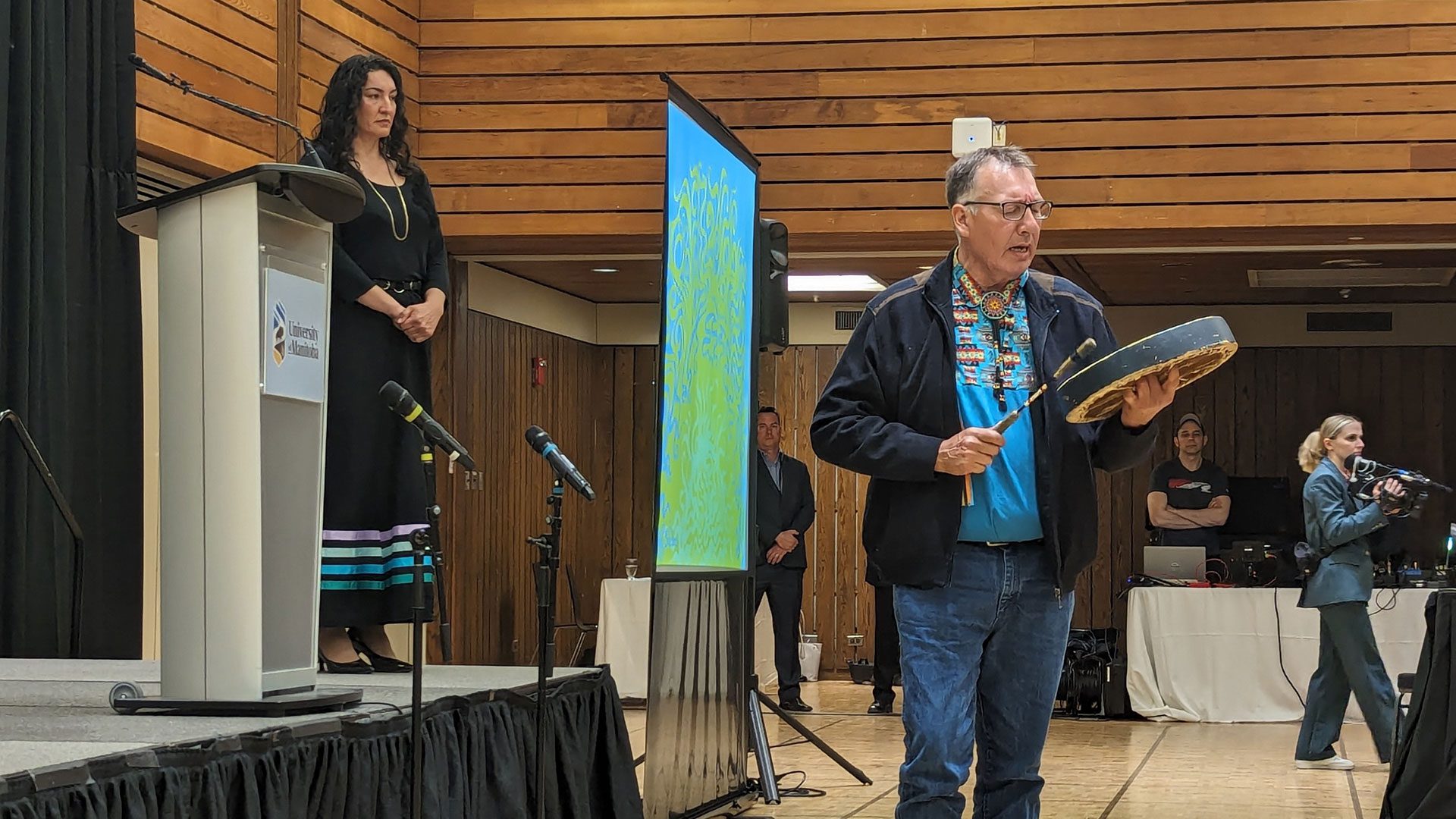

Its president, Michael Benarroch, publicly apologized for the university’s “inappropriate” acquisition and housing of the collection on Monday.

“The Univesity of Manitoba did not live up to its ideals in their true form. Today, we begin by atoning for these historic failures,” said Benarroch, “We apologize for these past wrongs. We are sorry.”

Benarroch said the process of rematriating and repatriating – or the returning of the human remains and burial artifacts – will begin immediately.

The university began collecting the remains of Indigenous ancestors at the turn of the 20th century.

“We used these ancestral remains and belongings in classrooms and in laboratories, and sometimes put them on display – all without consent from First Nation, Inuit, and Métis families, communities and nations,” Benarroch acknowledged.

Co-chair of the university’s Respectful Rematriation and Repatriation Ceremony, Lara Rosenoff Gauvin, said they acquired the remains and artifacts in different ways, including some brought to them by the RCMP.

She said the practice ended in the early 1980s.

In 2019, the university’s Department of Anthropology began asking Indigenous Elders on campus what they should do with the extensive collection.

“I’ve studied repatriation and, in many places, it is not done according to Indigenous ways,” said Rosenoff Gauvin, “so we approached the elders and apologized as a department and asked what would be a good way to move forward.”

Since that time, the university has created a new policy at the recommendation of the elders council on how to repatriate the ancestral remains, which includes reaching out to affected communities for their input.

So far, 10 have been contacted, including the Haida Nation in British Columbia.

Co-chair of the Haida Repatriation Committee, Lucy Bell, was in attendance and said she first learned about the phenonemon of institutions housing human remains 30 years ago.

“So today, when I witnessed so many emotions in the ceremony this morning, I get it,” said Bell. “To learn about ancestors being in drawers, in paper bags, in stapled little baggies … it’s horrific. It’s devastating.”

As of 2021, Bell has helped return more than 500 sets of remains to Haida Gwaii, north of Vancouver Island.

Now, she’s adding a few more.

“Tomorrow,we take home four of our ancestors from this institution, and it’s not easy work. It never gets easier to be handling the bones of our ancestors,” said Bell.

She hopes other institutions holding ancestral remains, like Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, will follow in the U of M’s footsteps.

Response from Indigenous students and faculty

Department head of Indigenous Studies, Lorena Fontaine, is also a co-chair for the Respectful Rematriation and Repatriation Ceremony.

She said it’s been hard for the university’s Indigenous students to know that their ancestors’ remains may be part of the collection.

“This acknowledgment is really important because it allows us to feel more at home here. To feel that our concerns and people matter,” said Fontaine.

Two students spoke during the apology to share their perspectives as Indigenous people on campus.

Graduate student Savannah Moon is doing her thesis on the rematriation and repatriation of the Indigenous ancestors held at the university.

She said the housing of the remains was an “open secret”, talked about by students and professors alike.

“One of the very first things I heard from other students when I [first came to] campus was to the effect of, ‘Did you hear they got Indian bones in here?’”

Social Work student, Amari Dion-Hart, says the U of M needs to acknowledge the struggles Indigenous students face on campus.

“We know that this institution was not created with us in mind, but we know that we come here every day hoping to make a change for our future.”