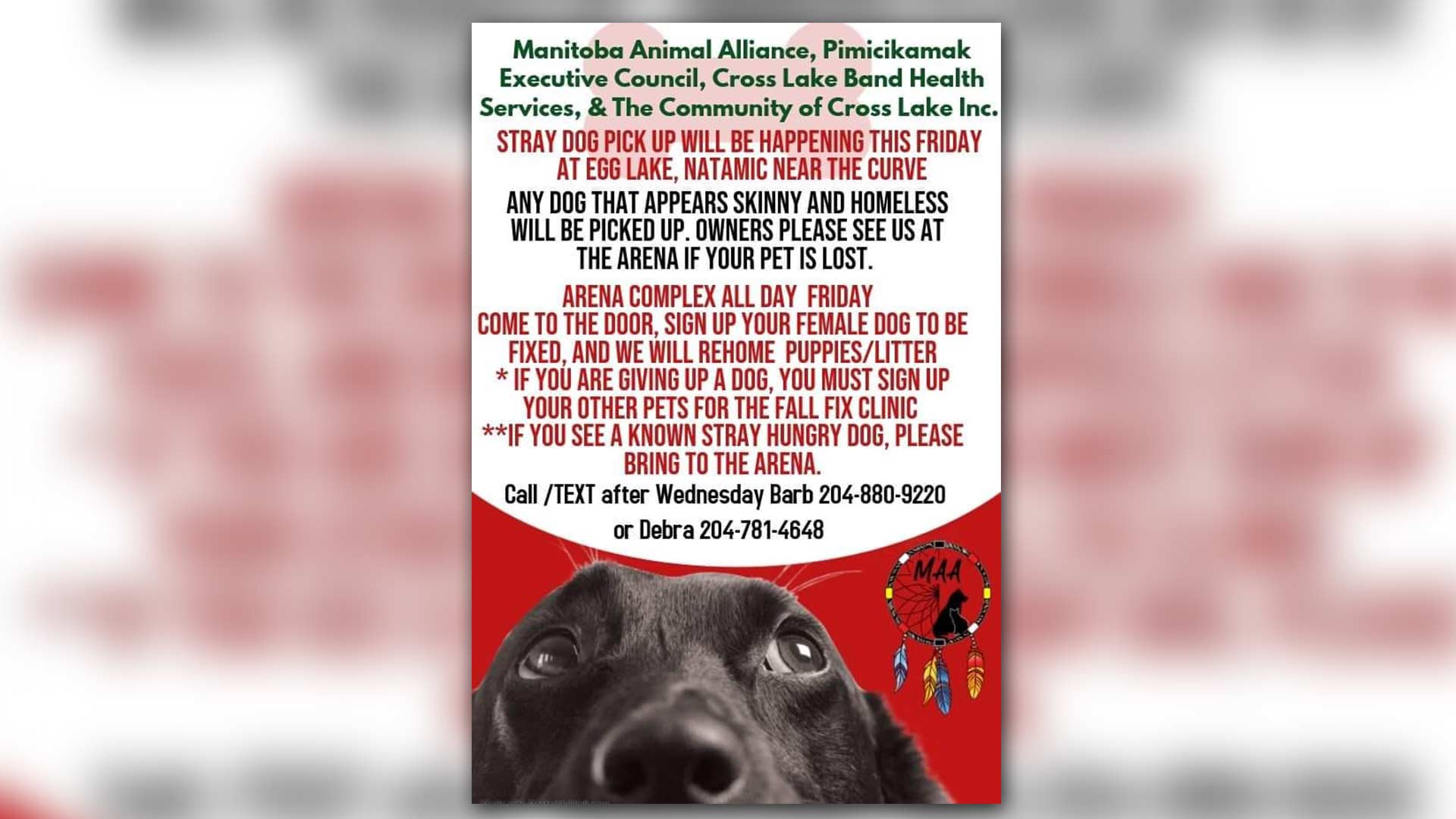

Some puppies picked up on a First Nation. Photo: APTN file

The Vancouver Humane Society (VHS) is taking a lead in trying to decolonize the animal rescue industry in Canada.

The organization is creating a training program for use across the country and seeking input from Indigenous Peoples.

“Part of what started this research is noticing the similarities within animal protection organizations of a colonial, child-welfare model,” said Celeste Morales, lead researcher with the VHS.

“Where white people go into the community and take the animal and say, ‘You’re not doing it right. We’re going to put this animal in a home with better people who can give the animal a better life.’”

Morales cited recent APTN News coverage of dog rescues gone wrong on First Nations that, she said, show the need for a country-wide, trauma-informed approach.

“No matter how closely you work with Indigenous communities, there needs to be learning and understanding more than just cultural sensitivity,” Morales added.

“But actual understanding of the history and ongoing trauma – inter-generational trauma – that has happened (and) why they might not want you to come into their community.”

She noted some online commentary about Indigenous Peoples on rescue group sites contains harmful and inaccurate information.

“Just because they have a different relationship with animals…does not mean it’s wrong,” she said.

“There is outrage that dogs live outside (or) they’re not necessarily pets.”

There are also unchallenged posts that dogs are regularly killed and routinely neglected that, in her opinion, signal a reckoning is due for the animal rescue system.

“It appears that harm is being done without a unified way of working,” Morales said in a telephone interview.

“There needs to be a lot more communication and collaboration.”

Dozens of animal rescue groups operate in Canada, run largely as charities by volunteers on social media that operate without government registration or oversight and rely on donations. There are more than 30 in Manitoba alone.

They may be well meaning but there is no national code of conduct or unified way of working or accountability mechanism when things go wrong.

“Hopefully, they want their story out there and they want their story to be heard on what they think would work better,” she said, (on) “what needs to be done (and) what needs to stop being done.”

Morales plans to discuss her early research at a national animal welfare conference. Her deadline to complete the project is at the end of June.

“If you’re wanting to work with (Indigenous) communities this is how you should do it,” she said of the proposed training program that will be available online for anyone to access, adopt and follow.

“We can improve these processes for everyone in a program that’s trauma informed and wants to take a decolonized approach.”

Morales said she is disturbed by “a form of seizure that’s not consented to” by rescue groups that “pull dogs in communities” by driving around and picking up ones that are roaming free, as described in some APTN stories.

“They think that’s normal and OK to do. These dogs are roaming around so why wouldn’t we take them?” she said. “But it’s harmful.”

Many rescue groups claim their mission to “pull” and “rehome” dogs helps Indigenous communities control stray, unwanted and even dangerous animals. But then they don’t have policies to return wrongly seized dogs when mistakes are made or even issue apologies.

Morales suggested more transparency and accountability is needed within the industry.

“This training will encourage a shift in mind as well as action,” she said.