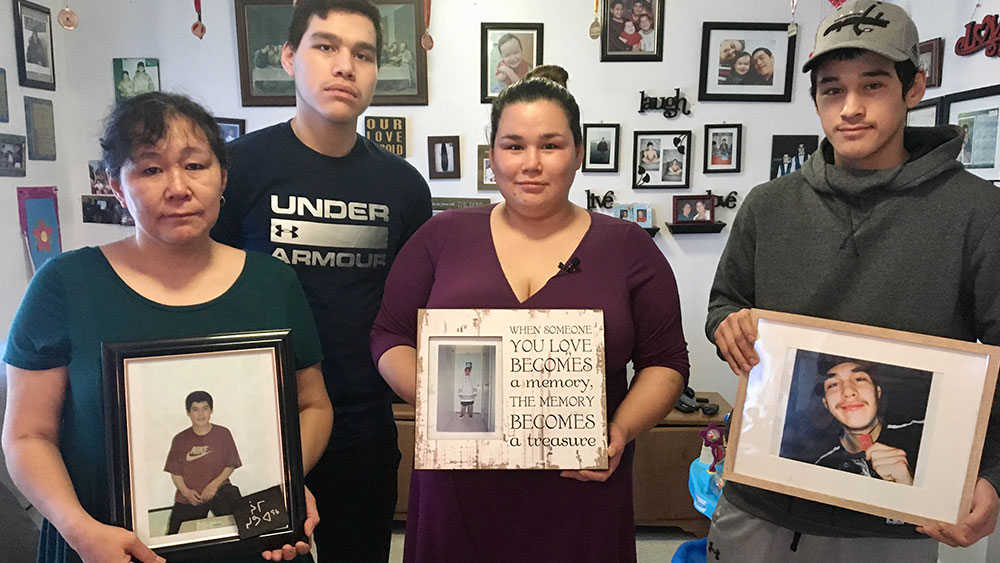

Louisa Eliyassialuk Surusilak is proud of her four children.

That much is obvious the moment upon entering her home in Puvirnituq, located in the Nunavik Inuit territory of subarctic Quebec.

The walls of the Surusilak house are covered in framed family photographs and more than a dozen medals hang from the ceiling of the living room.

It doesn’t take any prompting for her to pull out a tablet and play a video of her son, Jimmy Sivuak Eliyassialuk Surusilak, who everyone calls Sivuak.

In it, Sivuak is dancing a half tap dance, half jig hybrid style that is popular in the Nunavik.

The fiddle music is rapid, but Sivuak has no trouble keeping up, his heels kicking out and arms swinging in a way that is both intense yet graceful.

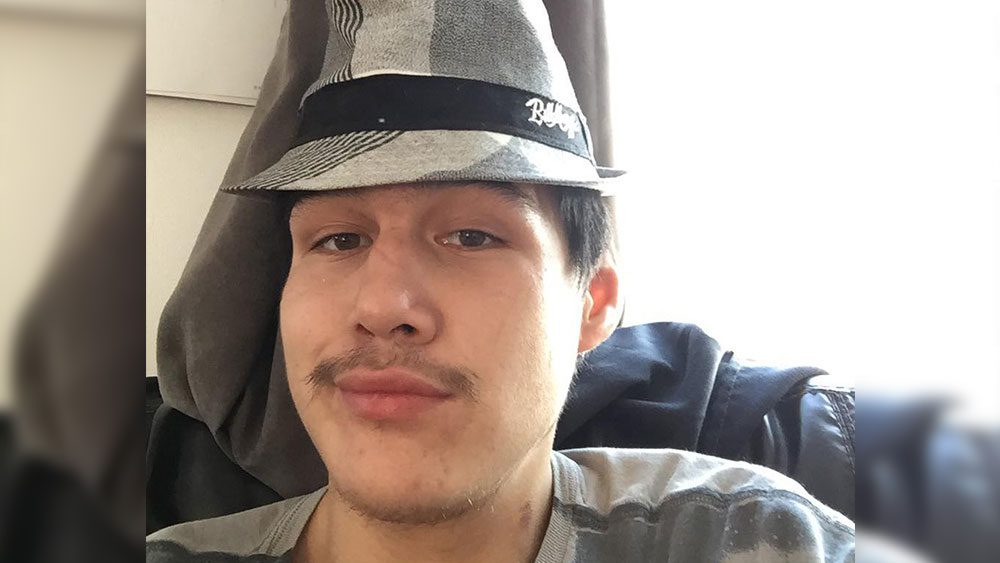

(“I hope I’ll see Ovechkin.” Jimmy Sivuak was a massive Washington Capitals fan. Photo: Facebook)

In the video the crowd roars when he finishes. Eyes fixed on the tablet, Louisa lets out a soft “hmmm” of approval, a thin smile on her lips – Sivuak took first prize in the Puvirnituq Snow Festival that year.

“His lifestyle was always energetic and nice, he liked to dance a lot, he was really competitive, he really loved it a lot,” Louisa says in Inuktitut, translated into English by her daughter Freddie.

Sivuak also loved hockey, especially Washington Capitals left winger Alexander Ovechkin.

On April 28, 2017 at 6:28 a.m. he posted this on Facebook.

“Gm (good morning). I hope I’ll see Ovechkin. Someday, in heaven lol”

Eleven Hours Later

The comment section of this post is now filled with broken heart emojis.

About eleven hours after its posting, Sivuak would be found dead in the local jail cell.

“They found out at around 5:30 p.m.,” says Sivuak’s sister Freddie through tears.

“And his body was already cold.”

According to a press release by Quebec’s director of prosecutions (known by their French acronym DPCP), the Kativik Regional Police Force (KRPF), who police the 15 communities of Nunavik, received a call at 9:20 a.m. from a man requesting help getting drunk people out of his home.

Two Kativik police officers arrived and took two inebriated men out of the house.

The release says police accompanied the first individual home, during which time Sivuak “appears to fall asleep” in the car.

“When he was too drunk why didn’t they bring him home or to the hospital?” asks Louisa Surusilak, her voice breaking.

The release says that the police took him to the Puvirnituq police station to sober up, an approach that “KRPF officers often perform in such a situation”.

At the police station, officers search Sivuak and place him on his stomach in a cell.

Sivuak is still unconscious; in the eyes of the police, he seems to be sleeping says the release.

(About eight hours after he was placed in a Puvirnituq cell, Sivuak was taken to the health centre where he was pronounced dead. Photo: Facebook)

The police statement then jumps to 5:13 p.m., when a civilian guard informs police officers that Sivuak is not responding to the guard’s attempts to wake him.

When police arrived, they find that Sivuak hasn’t moved since they put him in the cell.

A camera filming inside the cell shows that Sivuak never moved during his detention.

Officers’ attempts at resuscitation failed.

At 5:47 p.m., Sivuak’s death is made official after he is moved to the Puvirnituq health centre.

The cause of death is later found to be alcohol poisoning, although the pathologist cannot exclude the possibility of “positional asphyxia” where the nose or the mouth is accidentally obstructed to prevent breathing.

The Investigation and getting answers

Because investigators are unable to determine when Sivuak died, the possibility of asphyxiation does not factor into the pathologist’s report.

In addition, the DPCP says that Kativik police placed Sivuak on his stomach in an effort to prevent him from choking through regurgitation.

The release by Quebec prosecutors concludes that with regards to any charge of criminal negligence, there needs to be a clear “reckless disregard for respect for the life or safety of others” and that “the conduct must represent a marked and significant departure from the conduct of a reasonably prudent person.”

“When they arrested him, there was no guard. No one was there,” says Sivuak’s sister Freddie, who states that investigators told the family that there was no one to replace the overnight guard when Sivuak was brought in around 9:30 a.m. It’s unclear if a KRPF officer stayed behind to keep an eye on people in the jail from the time Sivuak was brought in until the evening shift guard arrived around 4 p.m.

“I’m still waiting for an answer, the results and for the papers,” said Sivuak’s mother Louisa.

APTN News requested information from Quebec’s Independent Investigation Bureau (known by its French acronym, BEI), the organization responsible for investigating incidents where a person dies or is seriously injured by police.

They were in charge of the investigation into Sivuak’s death. BEI is unable to give APTN the report, citing that it’s against the law to share police reports in Quebec without special approval from the ministry of public security.

The BEI directed APTN News to the Quebec coroner, who under certain circumstances can provide police reports.

The coroner declined to provide the documentation.

The Surusilak family were also referred to the Quebec Coroner, whose website is in French only.

The Surusilak family speaks Inuktitut with English as their second language.

In another attempt to verify Freddie Surusilak’s allegations that her brother was left unattended in the Puvirnituq jail cell, APTN made repeated requests to the Quebec coroner for their report of the incident.

The coroner uses the BEI investigation report to help determine what happened.

The coroner wrote APTN on December 10, 2018.

“The investigation is effectively completed, but the file must then be the subject of an administrative control (like all files)” and that the report “should be made public in a few weeks”.

Five months later and two years after Sivuaq’s death, the coroner report has not been made public, which they are obligated to do by law.

The coroner’s website says investigations usually take around eleven months

When asked why their report has yet to be made public, the coroner says they are still in the process of “validating” it.

The Police

APTN New also asked KRPF Chief Jean Pierre Larose for clarification on whether or not there was a guard on duty the morning of Sivuak’s death.

Larose declined to comment and directed APTN to the BEI.

But on November 22, 2018 in Kuujjuaq, Que., Larose testified before the Quebec Inquiry into the Relationship between Indigenous People and Certain Public services.

Inquiry Prosecutor Paul Crepeau pressed Larose on the state of the region’s jail cells.

Crepeau invited Larose to look through hundreds of statements made to the commission about them.

“We’re talking about serious problems with guarding,” Crepeau observed.

Larose, and KRPF Capt. Jean-François Morin told the commissioner that they don’t have enough officers to patrol communities and staff the jails. Because they want to make sure they have enough officers on patrol, KRPF hires civilian guards, but that they’ve been having recruitment and retention issues.

“I have appointed a captain, he is trying to revive the recruitment and hiring of civilian guards, because in some communities we do not have a lot of them,” said Larose, who added that the salary for guards has recently been increased from $15 to$22 an hour.

If for whatever reason there is no civilian guard, Larose says that an officer is supposed to do it.

“Of course, we cannot leave detainees in cells without guarding,” Crepeau responded.

“Absolutely not,” replied Larose.

The Jail Guards

Later on in the testimony, Morin said that the civilian guards are often non-Inuit who already work in the community in some other capacity.

“It’s a very variable schedule, on call, it’s not a job that’s sought after,” Morin explained.

It would also appear that there have been complaints made to the Quebec inquiry about the behaviour of certain guards.

“We were told about cold water, abuse, insults, not giving drugs, not providing basic necessities for life. Do you check these stories?” asked Crepeau

“If there are problematic cases that are reported to us, we will deal with them, of course. It has happened in the past that there are guards who have been fired for various reasons,” replied Larose.

Crepeau continued to press Larose, asking if there are any quality control measures with regards to guards.

“We know that Inuit often do not complain,” said Crepeau “I understand that you have no means to go over, to check the quality of the guarding?”

“No, we have not put anything in place,” replied Larose, before adding that he intends to do so.

This is not the first time jails in Nunavik have come under public scrutiny.

In 2015 the Quebec Bar association released a damning report on the state of the justice system in Nunavik, singling out the Puvirnituq jail as “disgusting and third world.”

(Watch Jimmy Sivuak dance a jig)

In 2016 Quebec’s Ombudsman released its own report, calling for major and minor changes to infrastructure to reduce crowding in jails.

According to a 2018 follow up assessment, the Ombudsman gave a mostly passing grade when it comes to sanitary conditions and overcrowding being improved.

Yet despite this follow up, Sivuak’s 2017 death appears to have gone mostly unnoticed.

The DPCP, who has the power to recommend the coroner do an inquest, did not.

The Quebec coroner would not say whether or not they will perform an inquest into the circumstances of Sivuak’s death.

KRPF declined to comment on whether they have adapted new protocols regarding dealing with severely inebriated individuals in light of the incident.

There also appears to be discrepancies in how the BEI views KRPF’s handling on the case

In a March 14th press release following the DPCP’s decision to not press charges, the BEI wrote:

“The information obtained during the investigation leads to the conclusion that the obligations of the police officers involved and the director of the police force involved provided for in the Independent Investigation Bureau Investigation by-law were met.”

This statement appears to contradict BEI leadership.

In a September 2018 personal letter obtained through an access to information request by the Ligue des Droits et Libertés, Larose is told by BEI Director Madeleine Giauque that they breached protocol regarding Sivuak’s investigation.

Giauque points out in the letter that contrary to the rules, an officer implicated in Sivuak’s case also served as a liaison to the BEI investigators, and that also in breach, the implicated officers discussed the case before drafting their reports and speaking with BEI investigators.

Meanwhile, KRPG Chief Larose has been public about chronic underfunding that he says leads to an understaffed police force.

In January, Public Safety Canada told APTN that an agreement in principle with the KRPF on a police funding had been reached.

But since then the agreement has fallen apart.

No organization appears to be investigating whether the chronic under staffing of the Kativik Police Force contributed to Sivuak’s death, or whether the KRPF should change protocols when dealing with extremely inebriated individuals.

The Family is Waiting

Meanwhile, two years after Sivuak’s death, the Surusilak family is waiting for the case files.

(Louisa Eliyassialuk Surusilak (Left) and family holding pictures of her deceased son Sivuak Surusilak)

Freddie is adamant that she wants to see the video from the jail cell with her own eyes in order to know exactly what happened, or didn’t happen, from that time Sivuak Surusilak entered the jail cell until someone found his cold body nearly eight hours later.

“We have the right to know,” said Freddie.

“Every day I think of him, how he died,” Louisa Surusilak added in a written statement translated into English.

“They took too long to find out he was dead.”