(Guy Dumas and Richard Yarema about to embark on a trip with APTN Investigates back to a former behaviour modification camp for young offenders in northern Saskatchewan. Photo: Christopher Read/APTN)

On an emotionally difficult journey through the past, two men who were sent to a behaviour modification camp as young offenders in the 1970s, recently returned with APTN Investigates to the remote facility’s site in northern Saskatchewan.

Last Resort is investigative reporter Christopher Read’s first episode for Investigates. The story chronicles the brief and violent history of “wilderness challenge” camps where the majority of campers were Indigenous.

Richard Yarema, 58 and Guy Dumas, 59, were teenagers when they were sent to a fly-in camp operated by the Ranch Ehrlo Society on Norbert Lake, Saskatchewan. The lake is a half-hour plane ride north of La Ronge, SK.

Watch Christopher’s video story:

Earlier this year, after major surgery, 58-year-old Richard Yarema of Dauphin, Manitoba felt he was at a crossroads in his life and he sent a letter to APTN Investigates.

Yarema’s letter painted a grim picture of his mistreatment at a behaviour modification camp for teenaged boys he was sent to in the mid 1970s as a young offender.

While in hospital recovering from open heart surgery, Yarema heard a voice telling him it was time to confront his past and address what had happened to him.

“I thought this was a chance to make things right. And to listen to that little inner voice that you do have. And my inner voice told me to get on with it and do it and it was confusing because I was still kind of loopy. But there were people talking and around me and they said ‘what did you say?’ Because I said real out loud. ‘Okay. I will,’” said Yarema.

Richard’s heart attack at age 16

(Richard Yarema at age 16 at Ranch Ehrlo’s wilderness challenge camp on West Norbert Lake. Photo courtesy: Richard Yarema)

Yarema, who is from Dauphin, Manitoba, was placed at the West Norbert Lake camp in 1976. He lived there with 15 or so other boys, including Guy Dumas, who was from Pukatawagan, Manitoba.

Incredibly, Yarema believes stress caused by the brutality of the camp led him to suffer a heart attack at age 16.

Yarema and another boy had stolen canoes and were caught about 24 hours into an escape run.

After they’d been brought back to camp, Yarema said they were beaten and forcibly stripped.

“’Oh you’re unclean, you’re this, you’re that,’” Yarema said he and the other boy were told. “We were stripped of our clothes literally while we were standing. Like ripped right off our backs, kicked in the back, punched.”

Next Yarema and the other boy had their hair cut, and then they were made to dig a pit for several hours, and were not allowed to rest or eat.

At a point when he thinks he had been without sleep for about 50 hours, Yarema remembers collapsing, feeling as though he had an elephant on his chest, and then having an out of body experience.

“And when I fell to the side I died, basically for a better word,” said Yarema. “’Because I remember being floating on top.”

Forty years later, after his recent open heart surgery, Yarema said his surgeon made a note on his chart and asked him a curious question: “He said, ‘When you were 16, did you have a heart attack?’ He said for sure I had a scar on my chest. Like on the inside of my heart. He said this shouldn’t be there at this point in your development of your heart.”

And Yarema also says his surgeon told him he had seen scarring on his lungs, which the doctor attributed to untreated pneumonia.

Yarema’s surgeon declined to confirm the account through a Winnipeg Regional Health Authority spokesperson.

But Yarema remembers having a serious lung infection at the camp, which staff members refused to take seriously.

“Oh it’s nothing and you’re just trying to get out of work,” Yarema said the staff told him.

“I told them no that’s not it, I’m spittin’ up blood,” said Yarema, “and I spit on the table … there was a big red blob with a big green glob in it.”

Nonetheless, Yarema said the illness went untreated.

Dumas says he also suffered neglect at the camp

Both Dumas and Yarema said that medical aid and/or evacuation for boys who were ill or injured just didn’t happen unless it was a broken bone or something more serious.

Yarema recalled being knocked out cold when another boy dropped a log they had been carrying on his head. He said the injury went untreated.

Another time, Yarema said he held another boy’s hand while the boy intentionally severed a muscle in his other hand with a bucksaw so he would be unable to work, and would have to leave the camp.

And Guy Dumas recalled an incident at the camp where he was forced to go on a hike though he was feverish and was in and out of consciousness.

“I became extremely, very sick.” He said. “I fell back from the group, like, I collapsed. I was just sweating profusely.”

Dumas said he collapsed a few more times before being allowed to return to the campsite.

“They decided I couldn’t hold the group back anymore,” he said. “I walked back by myself and I went straight to my bunk. No one checked on me.”

As well, both men recalled food and shelter deprivation, isolation and humiliation being used as punishment.

Wilderness challenge changed Yarema

Yarema says he came home from the camp after the licence was pulled. He’d been there about a year.

Haunted by the memory of being held down and slapped regularly in the camp, he taught himself to fight, and made a vow to never be treated like that again.

“I was 185 pounds and I swore to myself, I said nobody, I don’t care who you are. I don’t care how big you are. I don’t care how many of them you are. No one will hold me down and ever slap me again. No one will touch me again,” he said.

Yarema also connects his experience at the camp to his alcoholism.

“Soon as I got out I was only 17 but the first place I went was the bar after I seen my family. I don’t think I stayed a day sober for about 10 years. I went on a 10 year binge, he said.

His mother Pearl Yarema remembers how her son had changed when he got back from the program too.

“He was so quiet, kind of reserved and he didn’t want to talk about anything,” she said.

And one day she found him alone in the basement.

“He was cowered in a corner and he had his hands like this [protectively] and he was hiding like he made himself so tiny,” she said. “And it really upset me. So I said to him, I said honey what’s the matter? And he didn’t talk. He didn’t speak. So, I sat beside him and I held him, and I held him, and I held him. And I cried, and I cried, and I cried. And then all of a sudden he goes ‘Mom!’ I said are you ok Rick? And he said. ‘Yeah. Why?’ And I said – nothing, nothing Rick. I’m just glad you’re yourself again.”

It wasn’t the last time Pearl Yarema would see her son like that.

“He had moments like that, where he’d do that,” she said. “Like he would isolate himself so bad and he would just cower. Like almost afraid – like shaking. And I told my husband about it and he said ‘Oh my god what did they do to him up there?’”

Wilderness challenge history

The West Norbert Lake camp, which Yarema’s probation officer arranged to have him sent to in 1976, was a project of the respected Saskatchewan social services provider: the Ranch Ehrlo Society.

The basic idea was to transform a juvenile delinquent’s love of high speed car chases and breaking and entering into a love of pursuits more along the lines of paddling a canoe 50 miles across a lake or learning to survive in the woods.

Wilderness challenge was considered by some to be a promising new approach for dealing with the most challenging young offenders, those who were having frequent contact with the judicial system and at risk of facing adult court.

(Cover of Neill Armitage’s thesis which was the theoretical basis for Ranch Ehrlo’s wilderness challenge program. Neill Armitage also worked for Ranch Ehrlo, supervising the wilderness challenge program)

After an experimental version of the camp funded by the Donner Canadian Foundation completed a two-year feasibility study starting in 1973, the program began full operation at Flinthead Lake and at East and West Norbert Lakes in northern Saskatchewan.

Referrals came from social services agencies across the country.

The program housed about 60 boys when fully operational, but in 1977 the camps were abruptly closed by the Department of Northern Saskatchewan in the lead-up to a public scandal.

Shutdown, scandal and royal inquiry

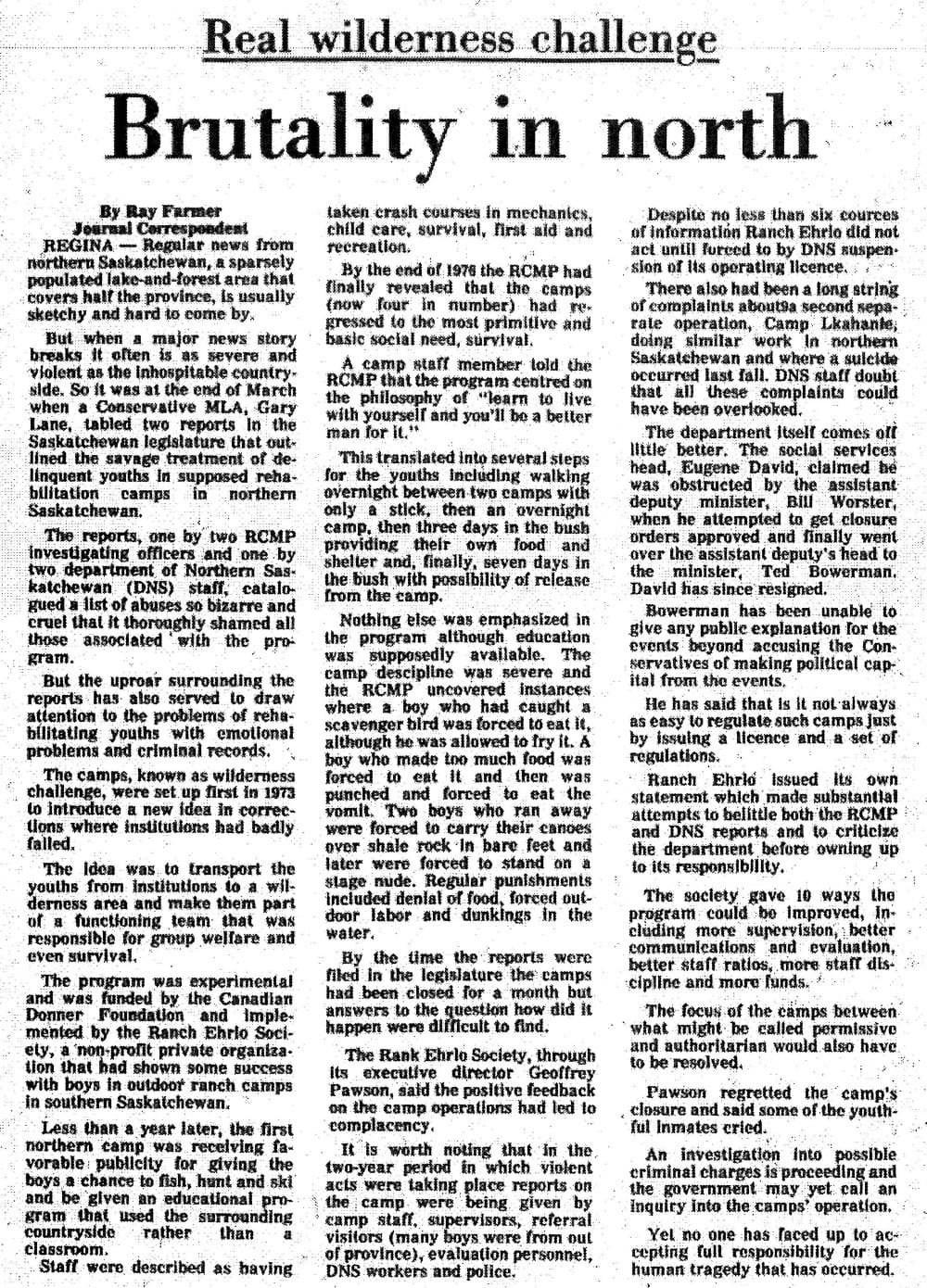

In March of 1977, Gary Lane, an opposition MLA in the Saskatchewan legislature, tabled notes from an RCMP investigation into alleged brutality and mistreatment happening in the wilderness challenge program.

The police investigation had been triggered when a camper in the wilderness challenge program named Donny Pedersen, now deceased, was apprehended by the RCMP in his home community of Buffalo Narrows. Pedersen was on a break from camp and after being picked up by the RCMP, had complained about the brutal punishments he and other wilderness challenge boys were being subjected to.

(Donny Pedersen at Ranch Ehrlo’s wilderness challenge camp in 1976. Photo courtesy: Richard Yarema)

When RCMP’s investigatory notes – as well as notes from a Department of Northern Saskatchewan investigation – were tabled in the legislature, the allegations of assaults and brutal discipline made headlines.

(News of the wilderness challenge scandal appears in an April 26, 1977 edition of the Ottawa Journal)

There was heated debate in the legislature and by June of 1977 a royal commission of inquiry into “wilderness challenge camps as proposed and operated by the Ranch Ehrlo Society” was announced.

In total, 51 witnesses were called, but just 13 were boys who had been placed at the camp. And neither Richard Yarema nor Guy Dumas were called to testify.

But Linda Hope did testify.

(Linda Hope, seen here in the mid-seventies when she was a social worker with the Department of Northern Saskatchewan. After investigating with the RCMP, Hope insisted that the wilderness challenge camps have their licences pulled. Photo courtesy: Linda Hope)

Hope was a mid-career social worker. She spent three days on the witness stand of the inquiry. After she had visited the camps with the RCMP, the licences for the camps had been pulled at her insistence.

“I went back to the director and said I’m not going to be responsible for licencing this program,” said Hope, “It’s not appropriate, it’s wrong. And there was a bunch of waffling going on but I said if you want to then it’s on your head. I don’t want to be responsible for saying that this is an okay treatment place for juvenile boys.”

Hope was horrified by what the boys were telling her.

“They were being beaten, they were being hit. They were not listened to. Nobody wanted to talk to them,” said Hope. “But mostly the discipline was so brutal. It was really, really hard to listen to when they talked about you know black eyes, things they were forced to eat, being humiliated if they did something wrong they would have to stand naked in front of the group.

“And then the others would shout different things at them because of what they had done. And each one of them had gone through humiliation in different ways with the staff.”

But Hope’s reaction to the allegations she heard – as well as her gender, were used against her by the commission of inquiry.

In the inquiry report, Hope was described as “emotional.” And she and a co-worker were even referred to as “girls” in the inquiry transcript.

While testifying before the commission, Neill Armitage, who wrote the thesis that was the basis for wilderness challenge, was asked about denial of food being used as a punishment.

Armitage confirmed that denial of food was used as a tool to modify behaviour.

“For example,” Armitage explained, “if an individual, say, refused to help out in collecting the firewood that would be used to prepare a meal – he wouldn’t eat.”

And when asked if deprivation of food might be a human rights violation, Armitage said he saw it from a different perspective.

“You know, using these tools of fear, hunger, fatigue, loneliness as a means of building character,” Armitage told the commission.

In the commission’s final report, some version of the alleged occurrences of slapping, punching, denial of food, humiliation, etc., were often acknowledged to have happened – but these incidents were usually minimized – often in light of the notion that the boys placed in the camps were “hard core delinquents” and this is what they sometimes required.

Commissioner John H. Maher – a judge of the District Court for Saskatchewan – authored the final report which cleared the Ranch Ehrlo Society of wrongdoing and found the decision to close the camps was unjustified.

But in the end, Ranch Ehrlo – suffering major revenue losses as well as staff layoffs and resignations in the wake of all the bad publicity – never re-opened its wilderness challenge camps.

Ranch Ehrlo today

In Ranch Ehrlo’s 2004 book about itself “Go Forward with Pride: A Historical Review of the Ranch Ehrlo Society,” editor Geoffrey Pawson, Ehrlo’s founder and long-time director, suggests that allegations of brutality by wilderness challenge boys came about because when investigators arrived the boys sensed an opportunity.

Pawson, who was away doing graduate work in California when much of the abuse was alleged to have happened, writes, “The residents picked up on the tenor of the questions and proceeded to tell them a range of made-up stories.”

When APTN Investigates took Richard Yarema’s and Guy Dumas’s allegations to Ranch Ehrlo, we asked specifically about that line in the book.

Malcolm Neill is Ranch Ehrlo’s vice president of residential services.

“I haven’t spoken to any of the boys about any of their experiences at wilderness challenge, said Neill. “I understand that the allegations were investigated by the RCMP and then there was the public inquiry. So I don’t know if they were made up or not made up.”

Responding to the allegation that Richard Yarema may have been put under so much stress that he had a heart attack at age 16 while in wilderness challenge, Neill said, “That sounds abusive. That is not something that we would – anyone at Ranch Ehrlo – would endorse today. I have no reason not to believe Mr. Yarema. I don’t know if he’s told that story to the authorities but I implore that he make a complaint to the police because that’s totally inappropriate.”

At the end of APTN’s interview with Neill, he summarized his feelings about the information we’d brought to him.

“I know what I believe in,” said Neill. “I know what the people who work at Ranch Ehrlo today believe in. And we certainly don’t believe in treating people – our children – the way they describe their experience.”

Going back to wilderness challenge

In mid-September, Richard Yarema and Guy Dumas went back to Ranch Ehrlo’s former wilderness challenge camp on what is now called Norbert Lake [formerly named West Norbert Lake].

The cabins, built by the boys in wilderness challenge, are still there. And the site is still used occasionally by Ranch Ehrlo for excursions.

Exploring the camp, Dumas and Yarema came across something they’d forgotten about – a wooden box built on a slope a little way from the cabins. A place, they said, where boys would sometimes be banished to for days.

(Yarema and Dumas say this is a partially re-built version of a box where boys in the wilderness challenge program would be banished for days at a time. Photo: Christopher Read/APTN)

“Yeah this is where if you got shunned this is where you got put. You weren’t even allowed to go here to see what it looked like,” said Yarema.

“It was restricted. You couldn’t come up here,” said Dumas.

“You got caught going up here you were in shit,” said Yarema.

“You’d stay here,” said Dumas.

The men said part of the original structure remained, but it had also been rebuilt since their time in wilderness challenge.

“This used to all be enclosed. There was no little holes like this. This was a little different,” said Yarema. “Someone rebuilt this thing out of nostalgia or some f**king thing. Now that I’m looking at it, this is more like a POW camp than any kind of rehabilitation bullshit that they said it was. It’s getting me angry.”

(The cabin Richard Yarema and Guy Dumas lived in while in the wilderness challenge program. Photo: Christopher Read/APTN)

But Yarema and Dumas were back at Norbert Lake to attempt a reconciliation with what happened to them there 40 years prior.

“I have to let it go, I’m almost 60 years old,” said Dumas, his voice breaking with emotion.

“And today I want to reconcile, I want to let go” he said.

With Yarema present, Dumas sang a Cree honour song through heaves of tears.

Afterwards the two men embraced.

Later, Yarema found the spot where he’d dug the pit and suffered a possible heart attack at age 16.

After softly retelling the story of what they’d done to him at the spot, the anger came back into his voice.

“They came up with punishments that came right out of a POW f**king movie,” he said.

Asked how he was feeling, Yarema said, “Ice cold. I’m just kind of vibrating inside. I haven’t had anyone to talk to for a long time. And Guy has opened up my eyes, in a lot of ways – for the forgiveness of stuff. I think I can forgive now. But I’m not going to forget. Because something like this you can’t forget. It’s going to be with you for the rest of your life.”