Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the Assembly of First Nations special chiefs assembly in 2015. Photo: APTN

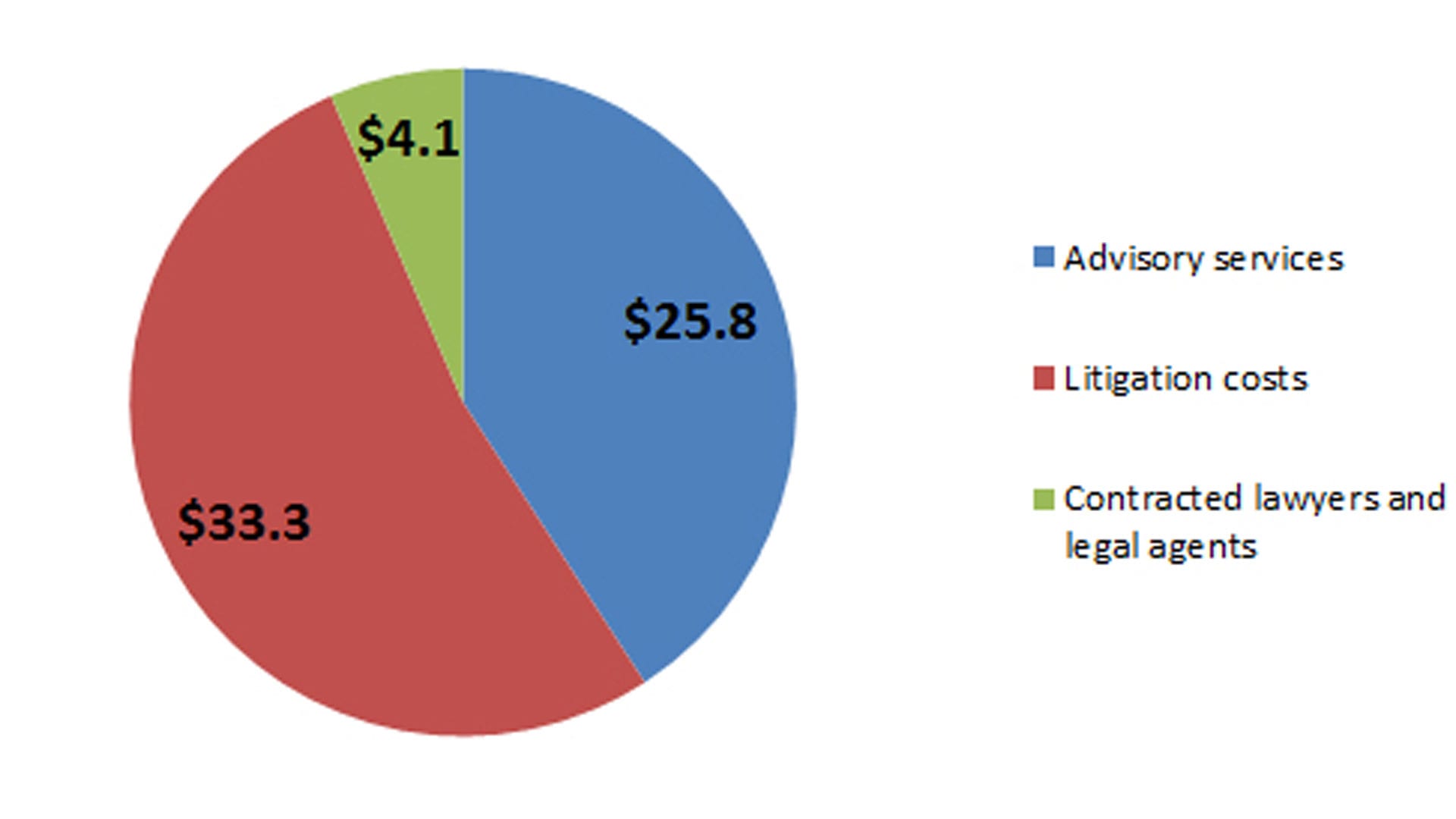

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) spent $58 million on legal services this last fiscal year, two times more than the RCMP or Defence Department respectively and more than any federal department other than the Canada Revenue Agency, according to public records.

CIRNAC counted 366 active court cases and 764 open but “essentially dormant” ones at this time last year, amounting to $6.6 billion in contingent legal liabilities. Its overall potential legal liabilities rose to $22.4 billion with land claims and other special claims factored in.

This figure made up 85 per cent of the entire federal government’s total contingent liability, making CIRNAC far and away the most sued and most legally exposed Canadian federal department.

“These are the really important numbers. I’ve said time and time again, to understand whether the government is serious about reconciliation, watch what they’re doing with the Justice Department lawyers,” said New Democrat MP Charlie Angus, who often criticizes the Liberals for the legal fees they rack up fighting Indigenous people in court.

After Angus asked via order paper, the Justice Department revealed it incurred $3.2 million in court costs fighting survivors of St. Anne’s Indian Residential School since 2013.

Last December, he submitted an order paper question that revealed Canada chalked up $5.1 million since 2007 fighting Cindy Blackstock and First Nations kids at the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, though documents Blackstock obtained suggest the figure could be closer to $8 or $9 million.

“The prime minister makes promises but the lawyers go in and they fight. They fight to limit the obligations of the federal government,” he said. “If you compare the money that Stephen Harper spent fighting Indigenous rights versus the money Justin Trudeau spends fighting Indigenous rights, you’re not going to see much difference.”

Trudeau spent slightly more cash on Indigenous lawsuits through his first three years in power than Harper did in his last three when the department was known as Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC)

Under Harper, INAC spent $92.4 million on litigation between 2012 and 2015. Under Trudeau, the department spent $95.9 million – $3.5 million more – between 2015 and 2018.

After winning power five years ago, Trudeau promised to reject the “adversarial,” “ineffective” and “profoundly damaging” approaches of the past.

“It is time for a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with First Nations peoples, one that understands that the constitutionally guaranteed rights of First Nations in Canada are not an inconvenience but rather a sacred obligation,” he told the Assembly of First Nations delegates in 2015.

Since that time, the former INAC complex – now split into CIRNAC and Indigenous Services Canada – has spent $346.9 million on legal services.

Angus says these numbers tell the real story.

“Justin Trudeau is more slick when he’s talking reconciliation, but we see on the ground, we see in the courts, we see in their legal battles this total toxic legal war that goes on outside of the eye of the public,” said Angus.

Trudeau’s CIRNAC has settled and paid out $3.1 billion – two thirds of it in 2020 – in claims against the Crown in the same span. The Harper government paid out $2.28 billion through a comparable five-year period leading up to his defeat.

The federal government posts all these numbers in various places on its website.

It’s not yet clear exactly how much money the Trudeau administration has altogether spent fighting Indigenous lawsuits because the breakdowns for the last two years haven’t been published yet.

APTN News asked CIRNAC for the figures but did not receive them by deadline.

Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett’s office said she wasn’t available for an interview.

The numbers that have been posted show that CIRNAC and INAC spent around $30 million per year on litigation between 2011 and 2018 with near clockwork regularity.

It spends the rest of the money mostly on Justice Canada advisory services for complicated transactions under the Indian Act and other legislation as well as comprehensive claims, self-government agreements, specific claims and constitutional matters of consultation and accommodation.

“Indigenous litigation is often of a complex nature and cases can be ongoing for long periods of time. The litigation can deal with issues that are historic in nature, which in many cases have been long standing grievances,” Bennett’s transition binder explained.

Transition binders are briefing documents that departmental civil servants write for their incoming political masters when new governments form. They bring politicians up to speed on key issues within their ministry.

The 2019 binder identified litigation as one of a handful of issues “currently in the public eye.”

“Though Canada has consistently favoured negotiations of these claims over litigation, it has been criticized in the past for its ‘litigate or negotiate’ policy whereby claims would be refused through negotiation processes if there was active litigation on the same issue,” it said.