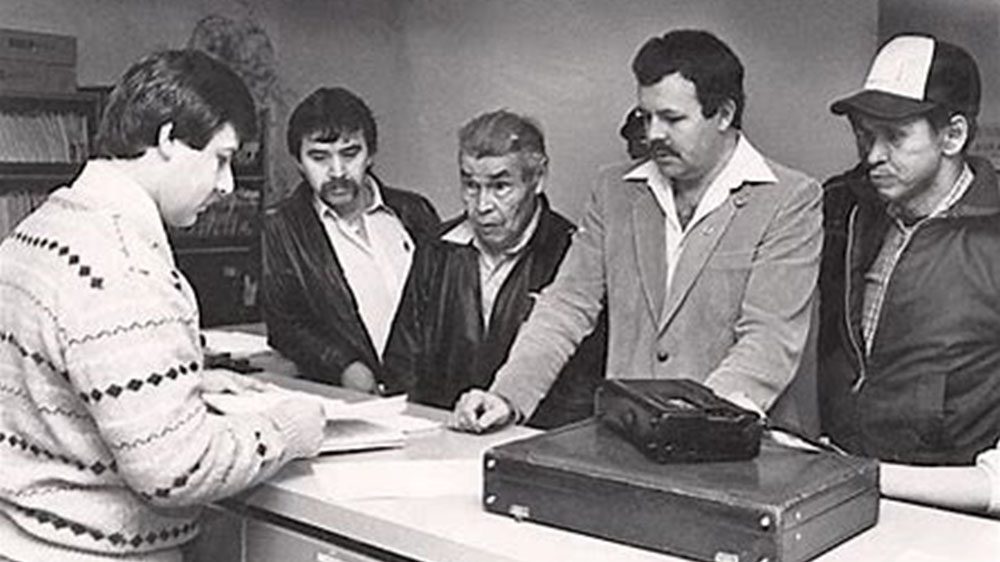

(Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs holding the 1991 B.C. Supreme Court decision, which ruled against them. Photo courtesy: Office of the Wet'suwet'en)

The conflict between the Wet’suwet’en Nation, the government and Coastal Gaslink didn’t happen overnight. They’ve been fighting for ownership of their language, culture and land since the day colonizers stepped foot on their territory. APTN News is producing three stories over the next week that will help fill in the gaps of how we got to where we are today. This is part two.

In a small Vancouver apartment, Yagalahl pored over transcripts into the morning hours, scribbling, making corrections, copying.

She didn’t work alone. The Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa case was underway and it demanded much work from many hands.

“I had to rent an apartment, and right in that apartment was where I had a group of volunteers who helped me where I had to go over the transcript and they had to go over anything that had to be corrected – and then we had to make copies of it,” she says.

“I must have had about 20 volunteers. We worked in the wee hours of the morning to have copies for each one of the lawyers that were handling the case: for the province and the feds and our lawyers. So that was quite a bit of work.”

Before it moved to Vancouver, the case spent 50 days in Smithers where the Elders and chiefs made their opening statements in Gitxsanimaax and Witsuwit’en, the two nations’ neighbouring but phonetically unrelated languages.

Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Satsan remembers how B.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Allan McEachern reacted.

“The Chief Justice is kind of getting beside himself because he doesn’t understand anything, and at one point he said ‘I need help. I don’t understand a word these people are saying!’”

But the plaintiffs predicted this and interpreters were ready.

“In advance of that we had trained and certified translators and interpreters,” Satsan tells APTN News. “Before the province or Canada could object, we trotted out our translators and our interpreters to help the Chief Justice, and he swore them in before either Canada or the province could object,”

Read part one: The Delgamuukw decision: Putting the Wet’suwet’en conflict in perspective

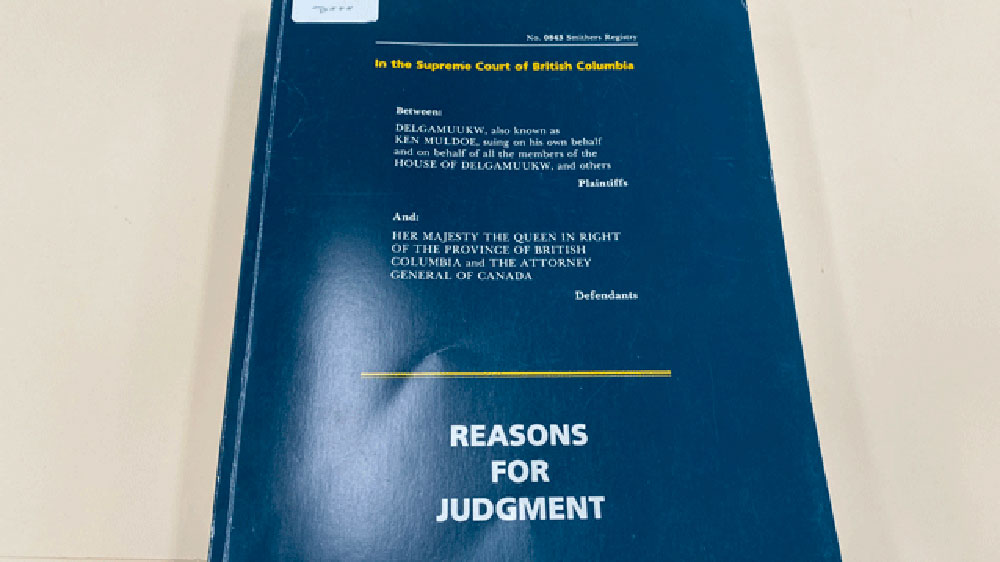

(At the Smithers courthouse in 1984. From left to right: an unidentified clerk, Victor Jim (translator), Delgamuukw (Albert Tait), Neil Sterritt (then-president of the Gitxsan-Wet’suwet’en Tribal Council), and Gisday’wa (Alfred Joseph). Photo courtesy: Office of the Wet’suwet’en)

Along with the translators, volunteers, and lawyers, the chiefs also employed anthropologists and mapmakers.

They employed Richard Overstall as a research director. He used his education in geology to map the hereditary chiefs’ traditional territories. They placed transparent overlays that showed the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en trails and territorial boundaries over government topographical maps.

“These were prepared the night before almost,” he says.

Today, the magnitude of the case sticks out in his mind.

“It was a huge undertaking on everybody’s part. There weren’t any real precedents for that kind of trial. So I think all of the plaintiffs and the government respondents – everybody was kind of making it up as they went along in terms of what type of evidence is needed, how it should be presented,” he recalls.

“What got us through all that was the plaintiffs’ strategy of telling all of us – lawyers, researchers, academic witnesses – that the central experts were chiefs and Elders and that the other evidence was to be presented in support of them.”

“This was, of course, a reversal of the usual court nomenclature where qualified professionals or academics are the ‘expert’ witnesses and the people themselves are the ‘lay’ witnesses,” Overstall explains.

That reversal was key.

The chiefs and Elders stood on their own laws, their own languages, their own ancient customs. It was a show of cultural and national sovereignty – an act of resistance against the colonial government that had banned the feast hall and tried to erase their languages through residential schools.

There was no question in the chiefs and Elders’ minds that they owned their ancestral territories.

“That is why we went to court: to show that we had the rights to our land, the territories that belonged to us for thousands of years. We needed the recognition of the ownership and jurisdiction of those lands. We had to have that – and we had to even prove that we existed. They even tried to say that we didn’t own any land because we had acquiesced to the colonialism,” Gitxsan Hereditary Chief Yagalahl of Spookwx House says.

“For example, that we had windows on our houses – now what does that have to do with anything? It’s crazy. Sitting in that courtroom, I heard so many crazy things from those lawyers, questions that were asked which showed that they didn’t have a clue of who we were!”

(Gisday’wa Alfred Joseph, centre. Photo courtesy: Office of the Wet’suwet’en)

Opening the sacred history box

Everyone worked hard to prove who they were and who they are.

Hereditary Chief Gulaxkan speaks fluent Witsuwit’en and was one of 13 certified translators: eight Wet’suwet’en and five Gitxsan.

Only three remain.

They spent hours listening to Elders recount their nations’ sacred histories.

“At that time, everybody was [raised on the land] – because everybody trapped and lived in the territory. So most of us were lucky to be born in the territory. I’m one of them,” she says of why she was chosen.

“We all had tape recorders and we visited every Elder within the community and spoke our language, and we interviewed them about their names, their territory, and all their regalia, the boundaries within the territory. That’s how all the maps came up,” says the 80-year-old Grizzly House matriarch.

“The eight of us, we were so busy travelling along interviewing the Elders and then brought it back to the office and we were translating them. And that’s where the books came out.”

Gulaxkan agrees with Yagalahl: “We worked hard.”

One day Gulaxkan raced over to pick up Chief Kweese, the late Florence Hall, from her house by the railway.

“They wanted the name of the place where she was when she was growing up. And they told me to go pick her up.”

Kweese, the chief of Beaver House and Tsayu (Beaver) Clan, was going into her eighties, says Gulaxkan.

Kweese would have remembered the days when feasts were illegal, when “Indians” weren’t allowed to assemble, hire lawyers, or pursue land claims under the Indian Act.

In court on another occasion, Kweese told the history her grandmother told her about a former Kweese who made war on Kitimat 400 years earlier.

“He was the same person that had visions and prophesized things,” said Kweese of her predecessor.

One of that former Kweese’s wives and child went missing while out on the territory. A strange visitor told Kweese who killed them. So he gathered an army and marched west to Kitimat and attacked a village there. The history spares no details of that violence.

In the end, after the drama of Kweese’s retribution raid, the history explains “why now the different clans have all these different crests and regalia. That is why they have crests now.”

Detailed questions from the lawyers followed.

“So that’s how we conducted our case,” says Satsan.

“It was based on ownership and jurisdiction. All of our evidence was based on our oral histories and our creation stories, and from the start of the case there was an issue from Canada and the province’s lawyers about admissibility of oral history.”

Yagalahl sat in court and watched lawyers question her chiefs and Elders after they told their kungax and adaawk – the sacred Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan oral histories.

The Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan knew their approach would create friction and cause objections. The conflict between different legal systems, languages, cultures, and governments was obvious.

“When we were arguing this, we were going into a foreign court. We were using somebody else’s law,” says Satsan. “But we went in there standing on our own law.”

And they were handed a tough defeat.

(Chief Justice Allan McEchearn’s 1991 written decision. Photo: APTN)

‘Nasty, brutish and short’: The ruling of Justice Allan McEachern

Chief Justice McEachern – an altogether different sort of chief – sat and listened for three years until the evidence was largely completed in 1990.

He visited the territories while the case was in Smithers and took a helicopter trip to study “this beautiful, vast and almost empty part of the province.”

He dismissed the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan claim for ownership and jurisdiction. He ruled their oral histories were hearsay and therefore inadmissible as evidence.

But he agreed with the plaintiffs on one thing.

“I must decide this case according to what they call ‘the white man’s law,’” McEachern said in an introduction to his nearly 400-page Mar. 8, 1991 written decision.

In a frank, stirring postscript to that ruling, he raised many issues that remain unresolved today.

First, he suggested the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan abandon their legal quest for rights.

“The parties have concentrated for too long on legal and constitutional questions such as ownership, sovereignty, and ‘rights,’ which are fascinating legal concepts,” he opined. “Answers to legal questions will not solve the underlying social and economic problems which have disadvantaged Indian peoples from the earliest times.”

The answer was not sovereignty and rights but greater integration with Canadian society.

“Indians have had many opportunities to join mainstream Canadian economic and social life. Some Indians do not wish to join, but many cannot. They are sometimes criticized for remaining Indian, and some of them in turn have become highly critical of the non-Indian community.”

“This increasingly cacophonous dialogue about legal rights and social wrongs has created a positional attitude with many exaggerated allegations and arguments, and a serious lack of reality.”

“It is my conclusion,” he decided, “that the difficulties facing the Indian populations of the territory, and probably throughout Canada, will not be solved in the context of legal rights.”

These comments go on in this manner for another two pages, but his meaning is clear.

(Chief Yagalahl Dora Wilson. “I’m right here in front of you,” reads her quote on the banner. “How can you deny that I exist if I am right here?” Supplied photo)

Antonia Mills, an anthropologist who testified in court for six days, was shaken.

“What he was saying was just completely colonization put down all over again,” she tells APTN.

“I was really just upset and unhappy and distressed and upset. I just felt that this was not justice in the least. This was very, very, very unjust,” she says of the decision.

Mills, professor emeritus at University of Northern British Columbia, interviewed hereditary chiefs and attended Wet’suwet’en feasts from ’85 to ’88.

She was one the “so-called” experts – as Overstall puts it – that the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan hired to help bolster their argument.

Yagalahl remembers one of the chiefs crying.

“Let me tell you, when we all gathered in Vancouver in that office there, one of the ladies was very upset,” she says.

“How could they do this? How could they?” the chief cried.

“No!” Yagalahl replied. “We have won – in a way. We have won a very, very interesting part of this because they say that we have only oral history and they wouldn’t accept that […] Now we have the transcripts. It’s written. What you’ve said is written. The history of our peoples has been written.”

“We were all pretty sad of the decision, and yet we still all had hope,” Gulaxkan says.

But Satsan is blunt about it.

“We lost. We lost big time,” he says, “and we lost on the fact that Chief Justice McEachern disallowed a lot of our – almost all – of our evidence based on the fact that, according to him, it was hearsay and could not be relied upon.”

“He said, more or less, we just made the whole thing up and, at best, he said our lives were ‘nasty, brutish and short.’ He was quoting from Leviathan,” a book by 17th century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes.

“He also misspelled Hobbes, so I always looked at that as the harbinger of things to come,” says Satsan.

Subsequent publications fixed the typo, but the original decision – complete with the misspelled philosopher’s name – reads as follows.

“It would not be accurate to assume that even pre-contact existence in the territory was in the least bit idyllic. The plaintiffs’ ancestors had no written language, no horses or wheeled vehicles, slavery and starvation was not uncommon, wars with neighbouring peoples were common, and there is no doubt, to quote Hobbs, that aboriginal life in the territory was, a best, ‘nasty, brutish and short,’” wrote McEachern.

It was tough to take. The chiefs and Elders believed if they told the truth that the truth would prevail.

Yagalahl refused to give up.

“If we don’t have a history, and we don’t have a language, and we don’t have a sacred homeland, and we don’t have our own spirituality, then we must not be a people, so we must be invisible – so we’re invisible people,” Satsan remembers Yagalahl saying.

“And that became the rallying cry,” he remarks. “We’re invisible people.”

The fight was far from over. McEachern knew they would appeal – and they did.

The chiefs and Elders rallied and took their appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Six years later, they came away with a victory.

But that victory had an asterisk.

Very timely to post this important story – thank you!