Gwich'in Council International Co-Chair Edward Alexander talks about the Arctic wildfires at the Arctic Circle Assembly 2023 in Reykjavik Iceland. Photo: Karli Zschogner/APTN.

Trying to put a wider spotlight on the global impacts of melting permafrost in the Arctic, Canada’s Dustin Whalen and Norway’s Tina Schoolmeester launched a new 174-page print and online Arctic Permafrost Map as an exhibit at the 10th Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik, Iceland.

“It’s the first atlas of its kind,” said Whalen, a scientist at Natural Resources Canada in Dartmouth, N.S., who helped to facilitate partnership with the Beaufort Delta Indigenous leaders. It’s an international effort led by Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research’s Nunataryuk, which maps underground and exposed permafrost including Antarctica, Russia, Alaska, and NWT Inuvialuit and Gwich’in communities of Tuktoyaktuk, Paulatuk, and Aklavik.

“World leading scientists on permafrost put their knowledge together to try to understand not only how the permafrost impacts at the local level, but at the global level with mind of the Indigenous people that live there,” Whalen said.

Whalen and Inuvialuk colleague Deva-Lynn Pokiak of the hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk, spoke on a panel on Climate Justice – dealing with permafrost thaw, and community-based observations. They were also featured at the assembly’s premiere screenings by BBC Natural History’s Interact ‘Disappearing Homes’ which is now available on Youtube.

“It’s a call for action,” said Whalen’s Norwegian collaborator Tina Schoolmeester of GRID-Arendal, a “non-profit environmental communications centre.”

“[Permafrost] doesn’t only store carbon, it also serves a lot of pollutants, and pathogens.”

According to scientists, Arctic permafrost alone holds an estimated 1,700 billion metric tons of carbon, including methane and carbon dioxide. That’s roughly 51 times the amount of carbon the world released as fossil fuel emissions in 2019.

“There’s still a lot of uncertainties around how this will be released, if it will be released, how the whole hydrographic pattern of the Arctic may change, when things are melting,” said Schoolmeester.

The conference in Iceland was attended by 2,500 people from 72 different countries. The goal of the meeting is to discuss everything related to people living in the high Arctic – from climate change, to food security and culture.

Schoolmeester said the atlas will also be displayed in Dubai, United Arab Emerites (UAE) for the next COP 28 – the world’s highest decision making body on climate issues that meets Dec. 3.

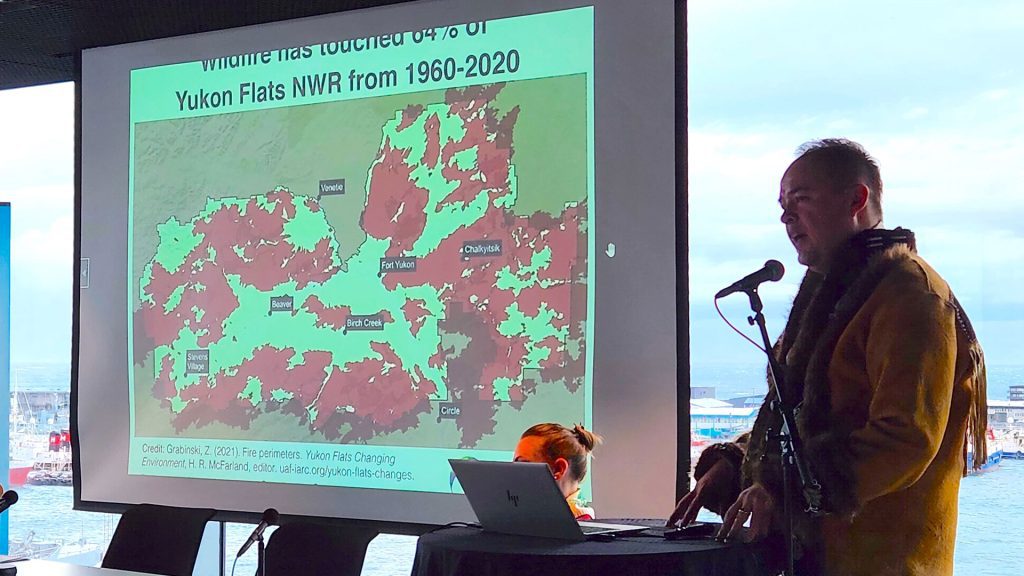

“Consider what role you have to play in helping us tackle the crisis of wildland fire in the north because the Arctic isn’t melting anymore, it’s on fire,” said Gwich’in Council International co-chair Edward Alexander alongside Yellowknife, N.W.T. mayor Rebecca Alty.

From Alaska to Russia, Alexander emphasized the importance of collaboration including with local Indigenous knowledge holders of cultural burning in fire management along the largest Boreal Forest region, highlighting not only the damaging loss of food and livelihood but increased rate of permafrost melting.

Alexander highlighted the Norwegian chair ship of the Arctic Council’s Wildland Fires Initiative (2023-2025) as an effort to elevate as an urgent climate change and increased carbon emissions. He said the initiative will support bringing together collective expertise, experiences and resources on wildland fires to identify knowledge gaps and best practices.

“Our voices are so important, especially as Indigenous youth,” said Zoe (Maniq) Okleasik, who is Golovin Alaskan Iñupiat from Nome, Alaska. She spoke during a protest outside the conference – and while on a panel on youth engagement and leadership.

Youth attending the conference were critical of the lack of action from world leaders including on COP 28’s UAE President-Designate Sultan Ahmed Al-Jaber’s responses to repeated questions on removing production of fossil fuels.

“It matters a lot to me [because] I lost my grandfather due to the changing ice,” she said. “He went out ice fishing and usually where the sea ice is strong, it was weak that year, and that was in 2015. And that same year, a lot of people lost their crab pots so people went hungry.

“It’s hard to talk about but it’s important to talk about.”

Geopolitical barriers to travel to Russian residents harmful for Arctic

Scottish researcher and professor Mhairi Beaton, was at the conference with her Sámi collegues sharing their ressearch how learning from one-banned Gaelic can support the revilization of other Indigenous languages.

She said it’s upsetting that representatives from Russia are not at the Arctic conference.

“Since the Ukrainian invasion … our Russian colleagues, who are scientists, who are researchers, are now isolated,” she said. “We need our Russian colleagues to be here to be part of these dialogues to be part of these projects.”

With over 40 Indigenous groups of peoples, Russia stretches over 53 per cent of the Arctic Ocean coastline including permafrost and accounts for nearly half of the population living in the Arctic worldwide.

Beaton said the narrow lens on just Kremlin government in news and other forms of media storytelling throughout history is harmful to the preservation of Arctic climate and culture.

“In the same way that currently with Israel, Palestine, and Gaza, I think it’s really important in our current society, to divorce political rhetoric and political decisions from individuals, and from communities because not all our colleagues in Russia will be approving of Kremlin actions,” she said.

Arctic Circle Assembly media director Matthildur María Rafnsdóttir said Russian citizens were welcome, especially Indigenous groups, however the main challenge since the Russian-Ukrainian war is getting visas out of Russia.

Wildlife Harvesting Rights for food security to entrepreneurism and ethical fashion

Arctic Inuit, First Nation, Sámi, New Zealand Maori and Columbian Kogi Mamos knowledge keepers are pleading for land preservation, Indigenous access to wild country food and wildlife management was also on the agenda.

“Our way of life has been colonized to such a degree that our food has been criminalized on many levels,” said Inuit Greenland assistant professor Qivioq Løvstrøm. “We’re still fighting many big entities as the UN and the EU on rights for to be able to sell seal skin, for example, which we have an abundance of. I even heard someone call them the ‘rats of the sea’ at some point because there is too many, and they were eating fish and fish is your main industry to the rest of the world.”

Learning from each other in Indigenous language revitalization

Added to the agenda was a panel on Indigenous language preservation including on Western Arctic Dinji Zhuh Gwich’in.

“I love how descriptive our languages are,” said Brandon Kyikavichik, Vuntut Gwich’in panelist from the fly-in community of Old Crow, YT. “I love how it can just instantly insert so much information into your brain.”

Kyikavichik described how he works in community on pre-contact language and history perseveration. He described English as a highly structured castle by the ocean where people have never left.

“If you want to learn our language, you have to come out of that castle, you have to step out of that highly structured environment, you don’t have to walk up to that ocean, you have to dip your toe in and get it wet, then you got to wade into it. And then after that, you just have to lay in it and just feel the fluidity of it and just completely let go of all that structure,” said Kyikavichik.

The next Arctic Circle Assembly is in October 2024.

Watch Karli’s video story on the conference: