Nympha Rich says she used to ask provincial authorities about her boys’ safety while they were in the care of the province.

She always got back the same message, “they’re fine.”

“I lost my son because of their system,” she tells APTN News. “He was in care for many years and I always got told my boys are safe and you don’t have to worry about.

“That’s what they always said.”

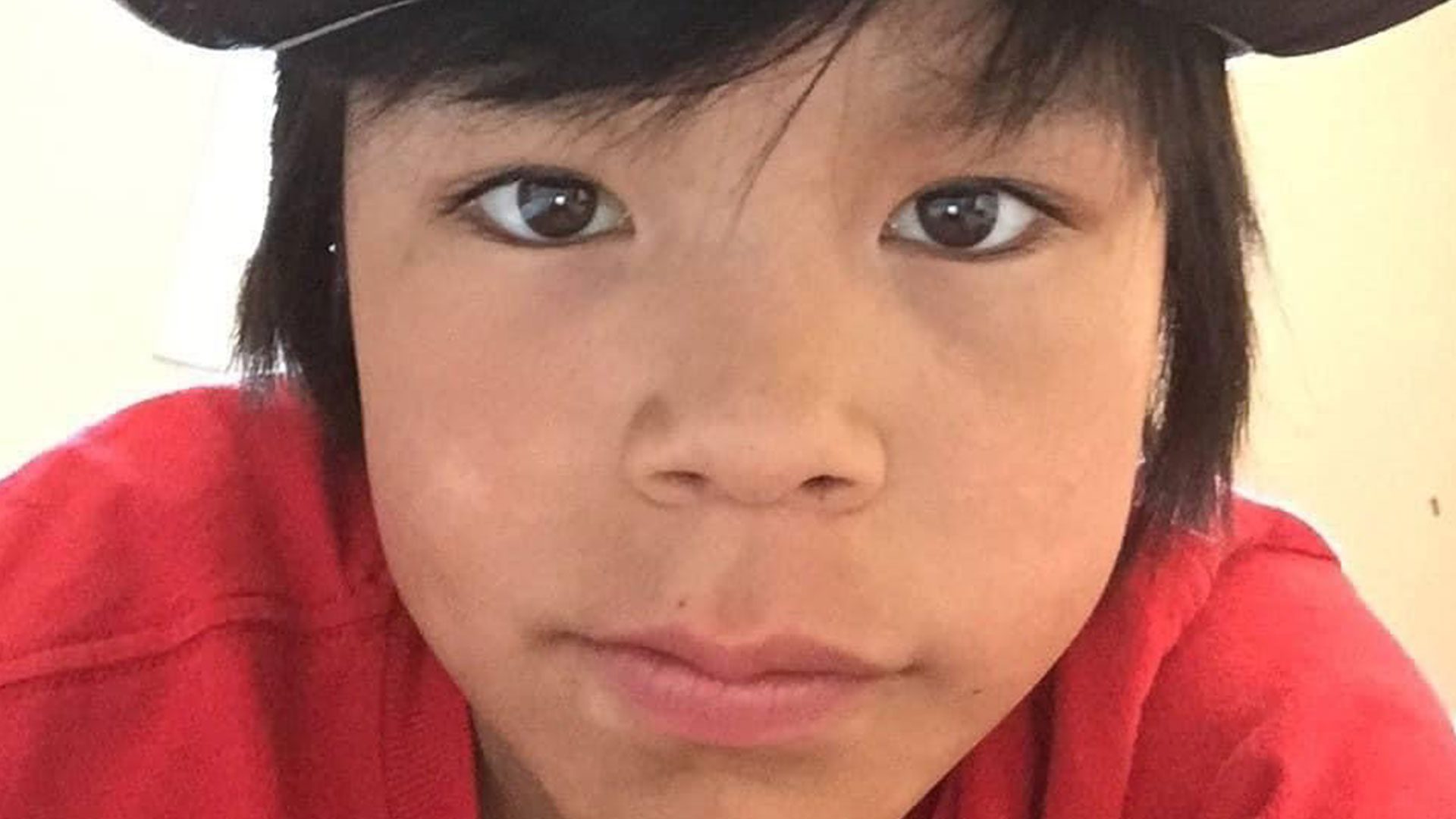

In 2020, Nympha’s fears became a reality when her son Wally took his own life.

He wasn’t alone.

Two other Innu children who were taken into provincial care also took their own lives.

The calls for an inquiry heightened when former grand chief Simeon Tshakapesh’s 16-year-old-son Thunderheart died by suicide.

The province said shortly after that it would launch an inquiry to the deaths and to examine the experiences of Innu children in state care.

But Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Innu Nation, wanted the federal government to be involved – and the start of the commission bogged down, further delays due to the pandemic.

On April 29, the provincial government announced that the inquiry will start in the fall.

“The mandate of the Commission is to examine the treatment, experiences and outcomes of Innu children, youth and families in the child protection system, and to identify recommendations for change,” said the provincial release. “The Inquiry will also include investigations into the particular circumstances leading up to the deaths of three youths.

On June 10, 2021, the province appointed retired Provincial Court judge James Igloliorte, Anastasia Qupee of Sheshatshiu and former grand chief of the Innu Nation, and former social worker Mike Devine as commissioners.

The Innu Nation includes Sheshatshiu, located 40 minutes outside Happy Valley-Goose Bay, and Natuashish, located an hour by plane on the Labrador coast.

At issues is that Innu children place in provincial care are often removed from their communities – and sometimes the entire province.

Innu Nation Grand Chief Etienne Rich, raised by his grandfather who was a nomadic elder, says their culture and language are lost impacting the entire community.

“They come back home after so many, several years, and they don’t have that language, they couldn’t even communicate with their grandparents, that is the sad thing about it,” says Rich.

“The system doesn’t work for us, and it has gone for so many years been like that and it’s time to change and to identify exactly what the problems are.”

According to the provincial release, all of the Innu issues identified will come up during the inquiry.

“The Commission of Inquiry is guided by a shared commitment of the Innu Nation, the Mushuau Innu First Nation, the Sheshatshiu First Nation, and the Provincial Government to ensure the safety and well-being of, and to act in the best interests of, Innu children and youth,” says the provincial statement.

The province has set aside $4-million for the inquiry which will take 18 months to complete.

According to Indigenous Services, “Canada will apply to participate in the provincially-constituted inquiry. The application to participate is mandatory under the Public Inquiries Act and must be approved by the Inquiry’s Commission. This approach is consistent with Canada’s participation in other provincially-constituted inquiries.

The email also said that the federal government is “committed” to ensuring that “a senior federal representative is present at the proceedings to answer questions and provide support to the process.”

Canada says it will also provide “potential witnesses and documentation” that are requested by the inquiry.

Indigenous services said it’s also providing funding for the Innu Nation to participate in the process.

Editor’s note: APTN News reached out to Indigenous Services on the day this report was published but none was provided. A spokesperson provided a statement on May 6 and it was added to the story.