The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that Native Americans whose territory straddles the international border can claim Aboriginal rights in Canada even if they aren’t residents or citizens.

On Friday morning the top court dismissed the Crown’s appeal and upheld the acquittal of Richard Desautel, a Sinixt Nation member from the Colville Indian Reserve in Washington state.

“This is a test case, the central issue being whether persons who are not Canadian citizens and who do not reside in Canada can exercise an Aboriginal right that is protected by s. 35(1),” explained Justice Malcolm Rowe, writing for the majority in a seven-to-two split decision. “I would say yes.”

Ten years ago, Desautel was charged with hunting without a licence after he shot and killed a cow elk for ceremonial purposes near Castlegar in southeastern British Columbia.

Sinixt traditional territory is sandwiched between Blackfoot and Secwepemc lands just west of the Rockies. It stretches up towards Banff, Alta. and spills over the border into northern Washington not far from Spokane.

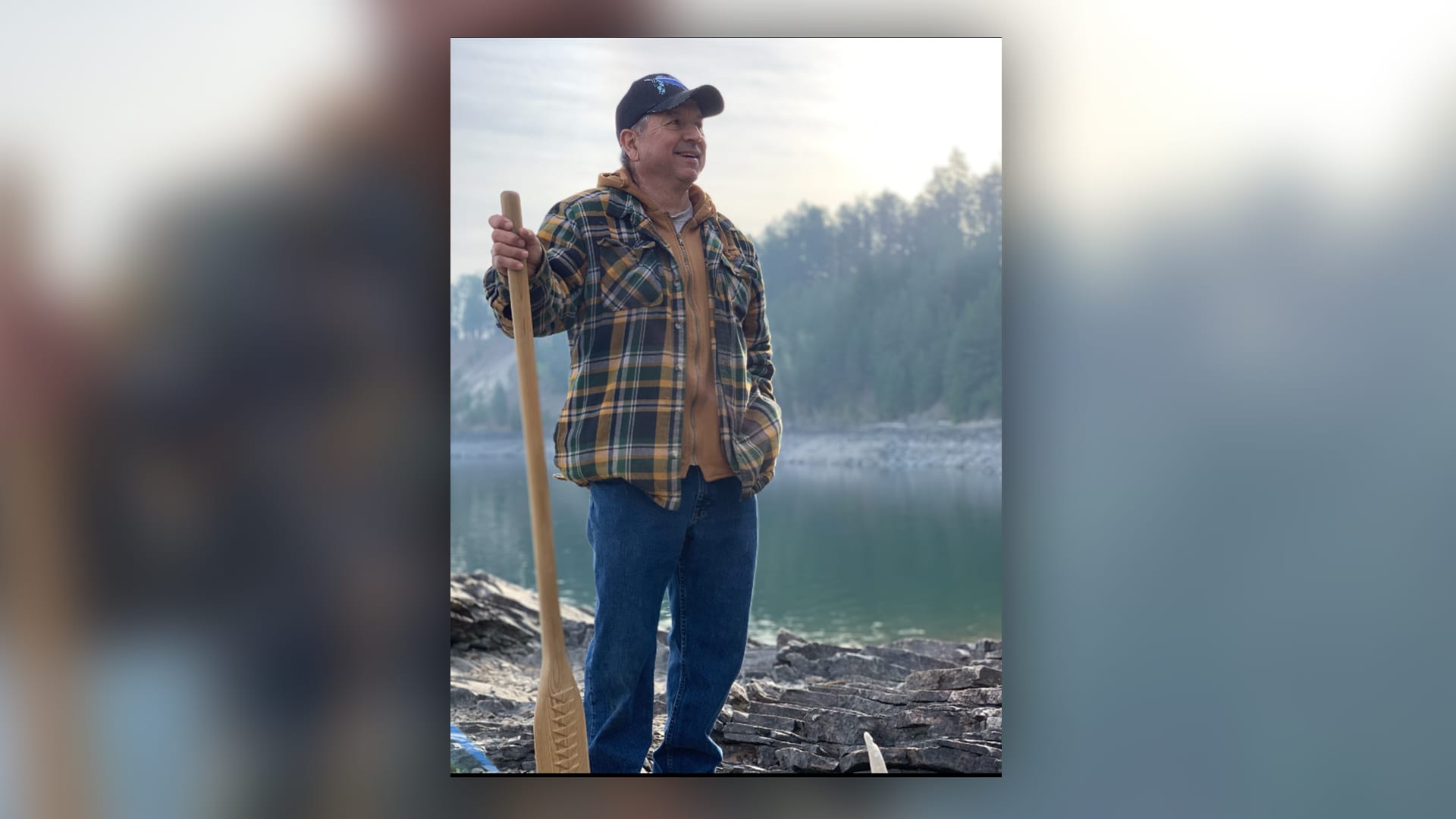

In a Friday afternoon interview with APTN News, Desautel described himself as jubilant now that the 10-year legal battle is finally over.

“For very anxious months we’ve been waiting for the decision,” he explained. “I myself was very relieved.”

He and a small group gathered at a culturally significant site in Kettle Falls, Wash. in the early morning hours to await the decision.

“Just the roar of the small crowd that we had there could probably be heard several miles away,” remarked Desautel. “It’s been a long time, and we’re very joyful in the decision.”

In his defence, Desautel admitted to shooting the elk and claimed that it wasn’t illegal.

He disputed the charges by arguing he was exercising an Aboriginal right to harvest under Sec. 35 of the Canadian Constitution.

Justice Suzanne Côté disagreed with Rowe, saying Sec. 35 rights don’t extend to Indigenous Peoples living outside Canada.

“A verdict of guilty should be entered on both counts of hunting without a licence and hunting big game while not being a resident,” she wrote, “and the matter should be remitted to the trial court for sentencing.”

Canadian law on Aboriginal harvesting rights crystalized in the ’90s when the high court issued a landmark series of controversial, high-profile decisions like Sparrow, Marshall and Van der Peet.

The Van der Peet ruling in particular laid out a test that courts still use to determine what constitutes an Aboriginal right.

Desautel successfully passed the Van der Peet test in B.C.’s lower courts, which acquitted him twice.

The courts accepted Desautel’ argument that he was exercising an Aboriginal right within the boundaries of his ancestors’ traditional hunting grounds.

But the Crown appealed the case and once again suffered a stinging defeat from the provincial appellate court.

Justice Daphne Smith dismissed the Crown’s arguments in no uncertain terms.

“The right claimed by Mr. Desautel falls squarely within the pre-contact practice grounding the right. Hunting in what is now British Columbia was a central and significant part of the Sinixt’s distinctive culture pre-contact and remains integral to the Lakes Tribe,” she wrote.

“The Lakes Tribe is a modern collective descended from the Sinixt that has continued to hunt and maintained its connection to its ancestral lands in British Columbia. Mr. Desautel is a member of the Lakes Tribe.

“Therefore, he has an Aboriginal right to hunt elk in the Sinixt’s traditional hunting territory in British Columbia.”

The Crown, she wrote, was asking the bench to essentially circumscribe when and where Indigenous Peoples could exercise their Aboriginal rights by requiring them to live within the exact same geographical area as their ancestors.

This requirement, she continued, “ignores the Aboriginal perspective, the realities of colonization and does little towards achieving the ultimate goal of reconciliation.

“In this case, such a requirement would extinguish Mr. Desautel’s right to hunt in the traditional territory of his ancestors even though the rights of his community in that geographical area were never voluntarily surrendered, abandoned or extinguished.”

The other dissenting Supreme Court judge, Michael Moldaver, said he was prepared to assume Rowe was correct on the question of whether Native Americans can assert rights in Canada, but that Desautel had not passed the Van der Peet test and should be found guilty.

“I would allow the appeal on that basis and impose the same remedy as Côté J.,” he wrote.

Right across Turtle Island, many Indigenous Nations find their territory slashed in half by the Canada-U.S. border, which is sometimes colloquially called the medicine line.

Rodney Cawston, chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, told APTN this is a significant win for these peoples too.

“This is a huge, landmark decision for the Colville Tribe, for the Sinixt,” he said. “But it’s also a very important decision for many other trans-boundary tribes from all across the United States and Canada.”

Cawston said he looks forward to strengthening unity among Sinixt members, increasing ties with the B.C. government, and working towards regaining Aboriginal title.

The federal government declared the Sinixt extinct in the 1950s. Cawston explained that the decision represents a significant victory in the nation’s fight for recognition.

“This is really exciting for us, especially for our future generations and our grandchildren,” said Cawston. “They can go up into Canada, and they can have that recognition and respect to be able to go back on their ancestral homelands and enjoy that country as much as our ancestors once did.”

The top court ruling could, potentially, require legislative or regulatory reform to accommodate and impact other types litigation.

Rowe noted in his reasons that “the duty to consult may well operate differently as regards those outside Canada.”

He also refused to speculate on how the ruling could impact Aboriginal title as this was not a question before the court.

“I would leave for another day the differences that may exist between the test for Aboriginal title claims by Aboriginal peoples within Canada and the test for such claims by peoples outside Canada,” he wrote.

Read the entire ruling here: 2021 SCC 17 R. v. Desautel