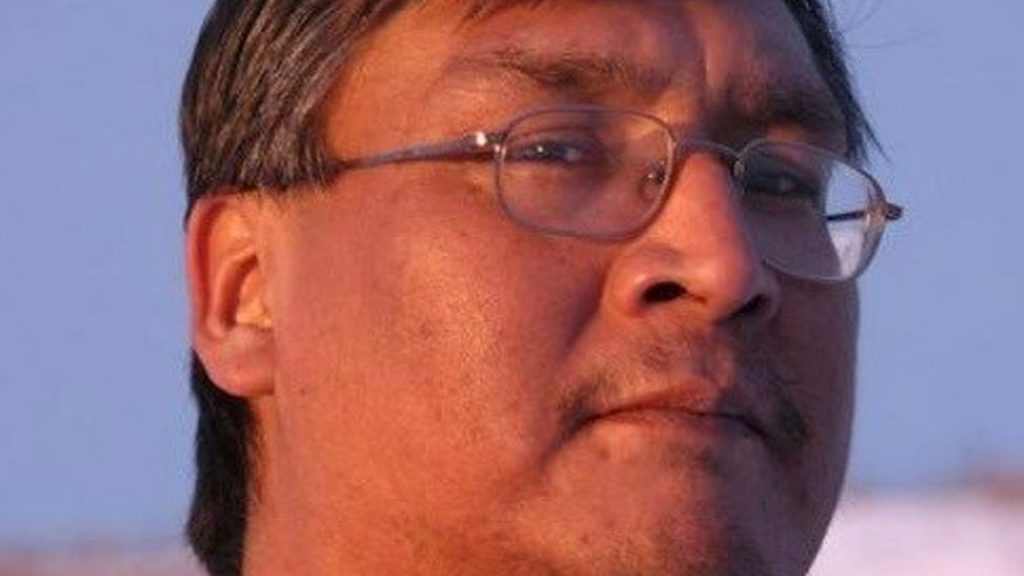

Darrell Night, whose name came to national attention after he raised alarm about Saskatchewan starlight tours has passed away at the age of 56 in British Columbia.

“He has left a footprint for many… his character was heartwarming,” said his brother Merv who told APTN that Darrell, who died on April 2, didn’t want to be defined by that one evening in his life.

“He was not the wealthiest man in the world but he would give out whatever he had in his pocket to help someone else.”

On Jan. 28, 2000, the Saulteaux First Nation member was dropped off on the outskirts of Saskatoon on a cold winter night by the Saskatoon police. Darrell was dressed only in a t-shirt, jeans, a jean jacket and running shoes.

He recognized where he was and was able to make his way to the Queen Elizabeth power station located on the edge of the city along the shores of the South Saskatchewan River. By banging on the door, he was able to get the attention of a security guard and get a cab home.

Darrell approached a city police officer in early February 2000 about the incident and it was investigated.

His story sparked awareness across the county about what are called starlight tours, a practice where members of the Saskatoon Police were dropping off First Nations people on the outskirts of town.

His story gained international attention and more information about the practice of starlight tours came out.

That’s because Darrell made his report days after separate discoveries of the frozen bodies of two First Nations men, Rodney Naistus, 25 and Lawrence Wegner, 30, near the same power station.

Darrell’s disclosure prompted an internal investigation.

Later in February, Stella Bignell spoke to media about the discovery of her 17-year-old son Neil Stonechild,’s frozen body in a remote industrial area on Nov. 25, 1990.

Darrell coming forward eventually led to an inquiry into the death of Stonechild that that investigated police involvement.

Officers Dan Hatchen and Ken Munson were charged with assault and unlawful confinement and eventually convicted of unlawful confinement of Night.

“Those cops tried to take my life… nobody deserves that,” Darrell told Tasha Hubbard in the documentary Two World’s Colliding about the cases that came to be known as the Saskatoon freezing deaths.

Seven years after Stonechild’s death a Saskatoon police officer, Brian Trainor, who wrote a regular humor column for the Saskatoon Sun documented two fictitious officers dropping off a drunk man on the outskirts of the city at the Queen Elizabeth power station.

The Star Phoenix reported on the articles as evidence police were aware of the practice of dropping off intoxicated men out of town.

Darrell Night remembered

Growing up, Darrell and his brothers loved sports.

“It was all sports. We talked about them a lot. Football and track and field were the main things. He was a really good quarterback… that is all we were was sports-minded,” said Merv.

After high school Darrell got a job in the trades.

“He was a bricklayer by trade. He worked on many projects in First Nations communities in Saskatchewan and Alberta,” said Merv.

In particular, Merv said Darrell was very proud of the school buildings on First Nation land he worked on, such as Carry the Kettle School.

He also explored his faith later in life.

“Darrell’s faith was really important to him. In the last eight or nine years of his life he re-discovered religion and attended church regularly,” said Merv.

He was working on book about his life when he passed away. His focus was not on his interactions with police but rather on how he moved forward with his life in a positive way.

A wake and funeral were held at the Saulteaux First Nation located approximately 150 km northwest of Saskatoon.

Darrell had three brothers and four sisters. Many of them would visit him in British Columbia where he moved to Vancouver to enjoy the warmer weather.

Darrell died from underlying health issues and a seizures, according to Merv.