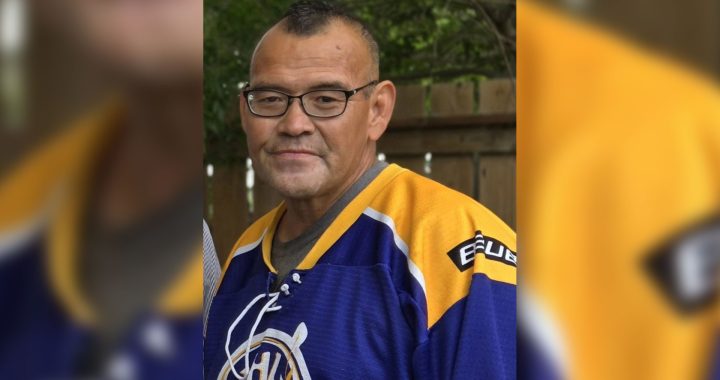

Nathan Kinbakset of the Splatsin First Nation stands in front of the sign he put up as a reminder that the popular tube launching spot is actually private property. Photo: Kelsie Kilawna/IndigiNews

As you drive down Cliff Ave. in Enderby, B.C., you will come to a bridge that passes over the rushing Shuswap River. On any given summer day, you are likely to see cars lined up all along the roadside on Splatsin First Nation.

Over the years, this area has become a hotspot for locals and tourists. It is also often used as a pit stop for tubers who launch upriver, as a spot to jump off and enter into town.

What most don’t know is that this entire riverfront – from the bridge all the way around – actually belongs to Splatsin Elder Nathan Kinbasket. He also owns the adjacent area that folks have been parking on.

Kinbasket has a certificate of possession on the area, which means his allotment has been approved by the Band Council, and he is able to lawfully use and occupy it.

He says he has been asking the public to access the beach on the other side of the river, and to respect that this is his land.

“All this straight on to where that sign is right there, that is all my property,” he says, while pointing north of the road.

“See where everybody is parking over here? They’re parking on my property, and last year they paved all this,” says Kinbasket, as he gestures toward his property line.

Kinbasket says the issue began when his grandmother allowed the public to access the waterfront because locals didn’t have a place to swim by the Cliff Ave. bridge that is adjacent to the Kinbasket property.

“The problem is, a long time ago, back in my grandmother’s day when we still had that wooden bridge here, she let the public come swim here,” he says.

“Because they didn’t have Barnes Park or anything, so out of the goodness of her heart, this was a swimming spot.”

The City of Enderby built the Enderby Lions swimming pool for the public at Barnes Park, a popular local spot for families. And, according to the City website, it is “one of the oldest public pools still operating in the province.”

However, all these years later, some of the locals and tourists still believe that the Kinbaskets’ land is for public access. He says they have resorted to destroying his many attempts at posting warning signs, clarifying his property is no longer open to the public.

“You know Indian Affairs gives you a lot of those signs right? The ‘no trespassing’ ones. I put those up and those are all gone,” says Kinbasket.

On top of the signage that Kinbasket says has been torn down multiple times, he has tried other measures that have gone ignored.

“We have dug a ditch so cars couldn’t go in there and we put posts in too, but some people came in with a 4×4 and pulled them right out,” he says.

IndigiNews reached out to the RCMP on the matter, but was told the force won’t release specific information “with regards to an individual or private property.”

Kinbasket is, however, trying to keep an open mind for his community. He says that if he fences off this land to stop the parking on and recreational use of his land, then the community members who walk along the road will not have a safe place to walk.

“I was even thinking of putting posts all along here, but if I do that, then I’ll be putting the band membership at jeopardy from walking here. I don’t want them to get hit or run over,” he says. “I really don’t want to put anyone in jeopardy. So I’m stuck in between a rock and a hard place.”

Highway expansion issues

Kinbasket’s concerns don’t stop with public access issues. He is pursuing legal action with B.C. Highways for allegedly widening the road onto his property, which he says was done without his consent.

“The highway is encroaching,” he says, gesturing toward where the highways paved over his land. “Last year, they paved all this…they put this road here without anyone’s permission.”

Kinbasket says that, over the years, B.C. Highways has been slowly moving onto his private property without consulting him, including putting up signage on his property.

“The current road location is a complex historical issue. The sign was installed over a decade ago. The ministry is looking to work with the certificate-of-possession owner and Splatsin to resolve the outstanding concerns,” says Peggy Kulmala, a representative from B.C. Highways and the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, via email.

In the meantime, hopeful of a resolution, Kinbasket says he will continue developing his property and renovating his home on the Splatsin First Nations.

More than anything, he says, he hopes that his community will remain safe.

“My biggest fear is with all those cars parking here, there’s going to be one major accident and I don’t want that here.”

Kelsie is reporting from the Okanagan for The Discourse as part of the Local Journalism Initiative. She’s a Sqilxw (Syilx/Indigenous) journalist and photographer who was born and raised in Inkumupulux (the head of Okanagan Lake). Her work is featured on IndigiNews.com, a new platform created by The Discourse and APTN.