The red honour roll is based on the national student registry. Photo: Danielle Paradis/APTN.

If you are feeling triggered by the events today, the Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line (1-866-925-4419) is available 24 hours a day for survivors experiencing pain or distress about their residential school experiences.

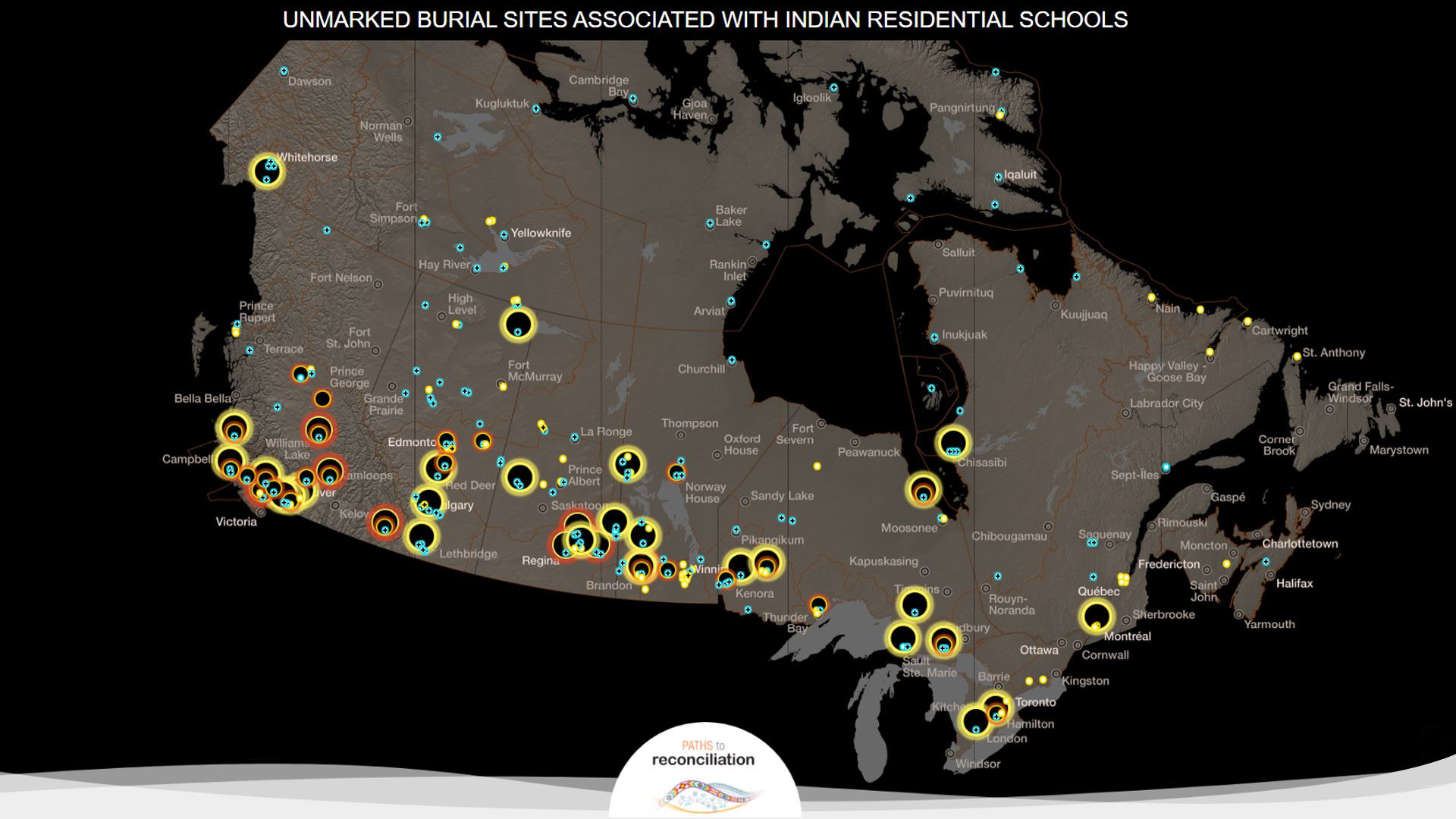

The discovery of 215 potential graves at the former Kamloops Residential School in British Columbia started a modern reckoning across Canada–and around the world.

Since then communities across the country have been doing their own searches and trying to find the records of children who went missing.

For survivors and their descendants, the search for truth remains a formidable quest.

The last residential school’s doors were shuttered in 1996 and living witnesses to this period endure, but the picture remains incomplete.

Kerry Gladue’s mother, who in life went by Jeannie Margarate Gladue but in school records was called “Jane Gladu,” didn’t talk much about her childhood as her son was growing up.

Although she physically survived the ordeals of residential school, she carried deep scars from that time.

“She didn’t talk about her life much…There were a lot of addictions growing up with her. A lot of suicide attempts,” Kerry told APTN News. He wrote a book on both his and his mother’s life stories.

“She was always with men who were abusive and there was a lot of alcohol and drugs.”

Jeannie lived on the street for some time in her young adult life before meeting a Métis man from Fort McMurray with whom she had three children, including Kerry.

She became ill with cancer in the 2000s and that is when she started to talk to Kerry and his brother and sister about her time in residential school. Jeannie went to Grouard, also known as St. Bernard’s residential school nearly 300 km northwest of Edmonton.

After the school was closed in 1961, Jeannie was placed in three different foster homes and a group home. He knows this because he has her medical records and records from the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

She brought them to Grouard Residential School when Kerry was 37 or 38. It was near the end of her life.

“She pointed out the place she knew children were buried, which they later confirmed,”’ he said.

In March of 2022, the nearby Kapawe’no First Nation uncovered 169 potential unmarked graves on the grounds of the former Catholic residential school.

Jeannie got the base amount that survivors recieved for being sent to residential school but she did not receive extra compensation meant for abuse victims.

“She was raped by a priest…every Sunday he would take her to his car and rape her,” said Kerry.

“She would come back with a bag of candy and that’s how the other kids would know. But there were no witnesses so she couldn’t prove it.”

After his mother passed, Kerry had a chance to look deeper at her records, obtained from the settlement agreement, as well as her medical records.

There are still some mysteries to Kerry and his family. His mother was taken from her parents when she was just over two years old and Grourard was the only home she had ever known. They do not know why she was taken from home so early.

Jeannie’s residential school was a home with a difficult history to acknowledge.

“She was always with men who were abusive and there was a lot of alcohol and drugs.”

Jeannie lived on the street for some time in her young adult life before meeting a Métis man from Fort McMurray with whom she had three children, including Kerry.

She became ill with cancer in the 2000s and that is when she started to talk to Kerry and his brother and sister about her time in residential school. Jeannie went to Grouard, also known as St. Bernard’s residential school nearly 300 km northwest of Edmonton.

After the school was closed in 1961, Jeannie was placed in three different foster homes and a group home. He knows this because he has her medical records and records from the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

She brought them to Grouard Residential School when Kerry was 37 or 38. It was near the end of her life.

“She pointed out the place she knew children were buried, which they later confirmed,”’ he said.

In March of 2022, the nearby Kapawe’no First Nation uncovered 169 potential unmarked graves on the grounds of the former Catholic residential school.

Jeannie got the base amount that survivors recieved for being sent to residential school but she did not receive extra compensation meant for abuse victims.

“She was raped by a priest…every Sunday he would take her to his car and rape her,” said Kerry.

“She would come back with a bag of candy and that’s how the other kids would know. But there were no witnesses so she couldn’t prove it.”

After his mother passed, Kerry had a chance to look deeper at her records, obtained from the settlement agreement, as well as her medical records.

There are still some mysteries to Kerry and his family. His mother was taken from her parents when she was just over two years old and Grourard was the only home she had ever known. They do not know why she was taken from home so early.

Jeannie’s residential school was a home with a difficult history to acknowledge.

Since that time, a country-wide search for answers has taken place community by community. Preliminary findings have been in the news and many communities are still in the early stages of archival research and working with third-party organisations to plan their search.

But the ground penetrating radar events that make the news do not tell the entire story.

“What technology can do is sometimes provide specific locations and it helps communities protect and commemorate and do those other kinds of things. But we’re not out to prove this. There’s already plenty of proof,” said Kisha Supernant, director of the Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archeology at the University of Alberta to APTN.

Read more:

How ground-penetrating radar is used to find unmarked graves at residential schools

With rising backlash and residential school denialism, Supernant said people need to understand more about the research that goes into finding children who went missing from their time in residential school.

“I think that’s a really important message because there’s been this pushback of like, ‘Well, no bodies.’ We don’t need bodies.

“We have thousands upon thousands of pages of records on children who died. Technology is useful, but it is not the only way to find answers,” said Kisha Supernant

In 2019, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), an organization created out of the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission that holds many of the archives related to residential schools, unveiled a blood red banner that was a student memorial of children who died in residential schools.

This grim register had 2,800 names and the centre acknowledged it was far from complete.

Shoddy construction and “extremely inadequate” ventilation at residential schools were reported by various federal officials in the early 1900s and were among the contributing factors to high rates of the deadly infectious disease, the report states.

“Underfunding … guaranteed that students would be poorly fed, clothed, and housed. As a result, children were highly susceptible to tuberculosis,” the report states.

Finding lost children

Raymond Frogner, head of archives at the NCTR, told APTN that the search for missing children is constantly evolving.

The current number of children who died at residential schools is 4,118, according to the NCTR.

“We are in the process of adding the work of our ‘Missing Children Phase Two’ project to this number…so it will change,” said Frogner to APTN.

“Everything changed in the spring of 2021 [with Kamloops discovery] followed by several other communities in western Canada. Up until 2021 our long term strategy was to go through four million records… and try and sort the identities and from that build a database,” he said.

Many of the records included the names of administrators, teachers, and ground keepers in addition to the students.

The 2021 discoveries “turned things upside down” said Frogner and instead the NCTR began focusing intently on unmarked burial site research with communities.

The NCTR is currently working with 25 communities and groups to find the names of missing children. They are also one of the repositories of records tasked with balancing the public’s right to know with the individual’s right to privacy.

When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission transferred its records, additional steps were taken to protect the survivors who didn’t want their residential school documentation to become public.

“There are some survivors who say ‘I do not want my records public’,’ said Frogner.

Although understandable, the protection of privacy can also be a significant barrier for researchers trying to get answers for their communities.

Nicole Marion-Patola is the director for treaty claims and residential schools at Know History, an Ottawa-based company that specialises in historical research.

Library and Archives Canada is still a key resource for researchers. That is where the majority of the attendance records are held as the archives for Indian affairs.

“Some of that material is publically accessible but I would say from 1940s onward a lot of that is restricted for privacy reasons,” said Marion-Patola.

Marion-Patola hopes to see a change in policy that allows some flexibility for communities trying to locate records.

“But that would take a lot of will to make changes to the existing rules,” said Marion-Patola.

“It’s really up to lawmakers to have that motivation to really push through change.”

Approximately 150,000 Indigenous children attended residential schools.

In 1883, Macdonald authorised through cabinet the creation of three residential schools for Indigenous children in Qu’Appelle and Battleford in the province now called Saskatchewan, and one in High River in what is now Alberta.

Public Works Minister Hector Langevin told the House of Commons at the time, “In order to educate the children properly we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that this is hard but if we want to civilise them we must do that.”

Egerton Ryerson produced a study in 1847 on Indigenous education at the request of the assistant superintendent general of Indian affairs. His findings became the model for future Indian residential schools. Ryerson recommends that domestic education and religious instruction is the best model for the Indian population.

His report, called “Industrial Schools” as that was his preferred name for the educational institutions.

History still being written

This chapter of history is still being written and re-written as more information comes to light.

Kerry believes in sharing stories of residential school survivors like his mother. He also believes that the truths, though difficult, need to be told.

“It is not easy all the time but it is good to get it out. It has got to be done and we can’t let the issue die down,” he said.