Pauline Fair moved away from her Ontario First Nation before she told police she was sexually assaulted by an Indigenous band constable, who later became chief.

That former chief was recently convicted and sentenced to three years in prison.

“All I can say for now is there’s wings,” she said of her 11-year saga to see her attacker punished.

“Get your brave on.”

But Fair acknowledged she wouldn’t have been able to endure the hate if she stayed in her home community.

Despite the #MeToo movement, which encourages women to speak out and society to believe them, Indigenous women often face judgement and backlash from their own communities and online.

It’s a phenomenon known as lateral violence that helps to silence victims and enable abusers.

Something Tasha Beeds, professor of Indigenous studies at the University of Sudbury, says needs to be challenged.

“Instead of being laterally violent, we can hold up our people,” she said.

“You have groups being created – Facebook groups being created – that support each other versus being laterally violent with each other.”

Beeds says social media – often used by offenders to groom and access victims – is also being used to expose wrongdoing.

“The #MeToo movement has had implication in Indigenous communities,” she said. “Predators do need to take note. There is shift in the Indigenous universe.”

Still, it can be risky and even dangerous to allege harassment in small and closely connected communities.

Melanie Hart, who alleged the former chief of Onion Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan was guilty of domestic violence in 2016, felt some in the community turned against her.

“People at court were afraid to look at me or say ‘Hi’ to me…because they were afraid of him. That’s their leader,” she said.

“A chief can take away your house, your job. He can cut you off of everything…I felt people believed him because of who he is.”

READ MORE: #MeToo Movement in Indian Country is out there – but it’s under cover

Tara Hart’s past was dragged into the spotlight in 2017 after media outlets received a tip about 14-year-old court papers involving her former partner Wab Kinew, who was running for the leadership of the NDP in Manitoba.

The documents showed Kinew was charged with two counts of domestic assault by RCMP, but the Crown stayed the charges and Kinew said his recollection of what occurred between the two was different.

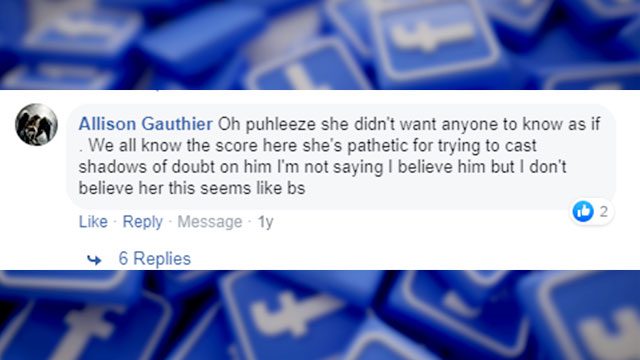

Hart was subjected to withering criticism.

“Oh Pluhleeze she didn’t want anyone to know as if. We all know the score here she’s pathetic for trying to cast shadows of doubt on him,” said one woman.

“Story sounds fishy,” added two others. “Why bring it up now? Dirty politics!”

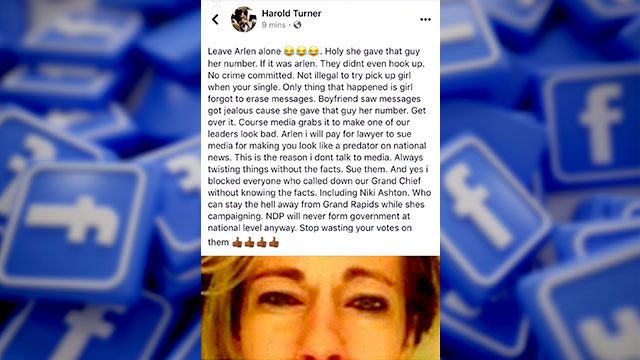

Bethany Maytwayashing, who complained on Facebook that Arlen Dumas, grand chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC), was sending unwanted texts “also received some serious, serious backlash,” said Beeds.

“Which, again, is a marker to me of just how much we still need to work at, how much we still need to stand up.”

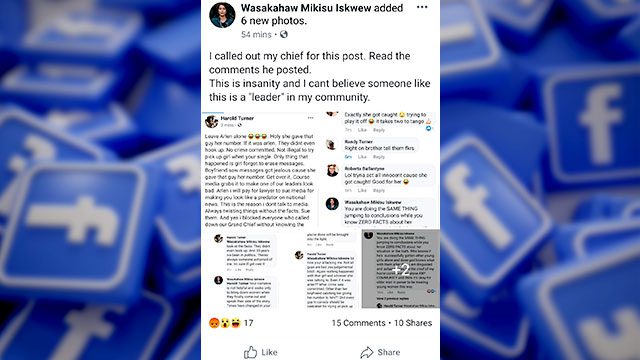

Harold Turner, chief of Misipawistik First Nation in northern Manitoba, showed his support for Dumas on Facebook.

Not everyone agreed that Turner, who couldn’t be reached for comment Friday, was in the right.

“I called out my chief for this post,” said a band member.

“…I can’t believe someone like this is a leader in my community.”

Even the media reporting on allegations of harassment can face resistance and resentment from the community.

This week, APTN News producer Beverly Andrews was kicked out of an event for seeking comment on the Dumas story.

“You know what is so frustrating?” said Anita Wilson, chief operating officer for Peguis First Nation, who ordered her to leave, ” our own media is the first to splash our dirty laundry all over the place.”

Still, Beeds, who has also been targeted for speaking out, believes media and technology are helping level the playing field for victims.

“Our (youth) are brilliant with technology, so if you’ve got someone who’s thinking they can go behind the scenes and act as a predator, we’ve got the tools and the knowledge to be able to use what we know as evidence.

“This gives us a certain amount of power.”

I truly believe our Human Rights as Indigenous are being swept under the rug. Where is our support? Why don’t we have a Indigenous First Nations/Inuit/Metis Human Rights and Ethics Commission. WE NEED ONE BADLY. And they need to be First Nations on the panel. This is getting out of hand.