There’s nothing unique about the first car that slowly crests the hill leading from Kanehsatake to Oka.

But then it’s followed closely by another. Then another.

This convoy, over 100 vehicles long, is rolling along highway 344.

Warrior and Haudenosaunee flags, soggy from the rain, struggle to catch any wind. Slow and steady, the convoy pushes forward, mostly silent save for the soft swish of tires on wet pavement. This is not a celebration, but a commemoration.

They roll past the site where the shootout with Quebec provincial police on July 11, 1990 left Cpl. Marcel Lemay dead.

They continue past the Kanehsatake cemetery and the golf club that threatened to overtake it 30 years ago. Driving down the hill made famous that July three decades ago to the day, when Mohawk warriors and Kanehsatake community members created a makeshift barricade of trees, tires, and an overturned Sûreté du Québec car. A barricade that would stand for 78 days.

Most know it as the Oka Crisis, but for Kanien’kehà:ka here, it’s called the “Siege of Kanehsatake”. Technically, it ended three decades ago. But for many who lived it, it’s never been resolved.

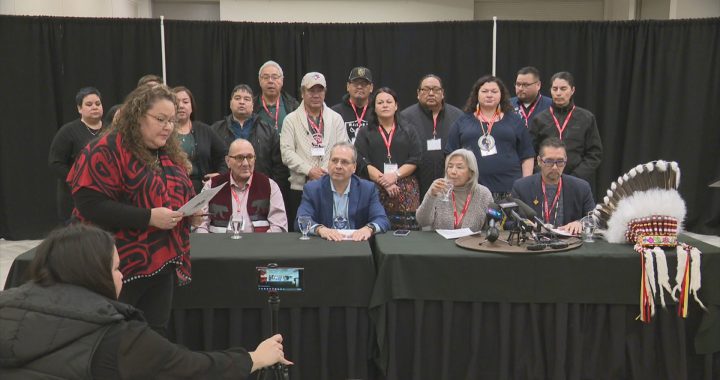

“Our ancestral lands still face theft and dispossession, our traditional governments delegitimized by the governments of Canada and Quebec,” said Ellen Gabriel, reading out loud a joint statement from both the Kanehsatake and Kahnawake longhouses.

Gabriel was a spokesperson at the Kanehsatake barricade in 1990. Today she found herself fulfilling that duty once again after the convoy finished driving through Oka, making a point to tour a condo development currently being built.

“The development we protested three years ago, which the government of Canada refused to intervene [in],” explained Gabriel.

The municipality of Oka is just one part of the wider land dispute Kanehsatake has been embroiled in for more than three centuries now.

APTN News spoke with Grand Chief Serge Otsi Simon earlier this week for an update on Kanehsatake’s land claim, the most recent incarnation of negotiations that have been ongoing for nearly a decade.

“There were some years we didn’t have any negotiation,” Simon said, adding things have improved slightly since the years of the Stephen Harper government.

“The repatriation of lands — that’s one of the sticking points,” he added. “There is an obligation by the crown, whenever these lands are available or undeveloped — they do have the justification to compensate the third party and get them off our Aboriginal title.”

Simon has been heavily criticized lately by fellow Kanehsatake members over the opacity of negotiations. Jeremy Teiawenniserate Tomlinson recently co-authored a letter demanding transparency over the land claim process.

“This is not customary at all for us,” Tomlinson told APTN. “Your job, if you represent me and this community at a negotiation table, is to go–you get the information and come back. Because how can you negotiate when you don’t even know the position of the people? How can you represent that position, when we haven’t told you?”

Tomlinson adds this isn’t only customary for Kanien’kehà:ka, but that Canada also encourages band councils to have an ongoing communication strategy with their members regarding land claims.

For his part Simon says Canada’s negotiation policies have left him stuck between a rock and a hard place.

“We have a confidentiality agreement with the feds,” he said.

“Policy of Canada says you got to keep the community informed. But then if you inform the community too much, you’re in breach [of confidentiality], and if you don’t inform them enough, well, then we have another problem. I’m sick and tired of it.”

Simon said there are negotiations scheduled toward the end of this month. Meanwhile, if Saturday’s anniversary events are any indication, Kanehsatake may have some allies in Ottawa.

“It is time that this longstanding land dispute be resolved, that it gets the attention that it deserves and requires from the current federal government to act now,” said NDP MP and Lakota Nation member Leah Gazan, who was joined by NDP leader Jagmeet Singh in Kanehsatake.

“To me what we’ve seen over the years is a lack of will to get it resolved,” Singh said.

“The Liberal government can count on me as an ally. I’ve made it really clear, this is an important issue for me. So if they need to pass any legislation, I’m there to help pass that legislation.”

Gabriel posed for a picture with Singh while holding the Two Row Treaty Wapum belt. Originally made with the Dutch over 400 years ago before being applied to all European settlers, the Two Row uses the simple design of two purple lines between three white to express independence between nations. The two purple lines travel down the river of life together, but never do they intersect.

“To honour and respect each other’s differences, to honour and respect each other’s way of doing things. To not interfere,” Gabriel explained, tracing her fingers along the purple wampum beads. “It has never been upheld by the settlers.”

After more than 400 years since the Two Row treaty, and now on the 30th anniversary of the Siege of Kanehsatake, Gabriel is clearly tired of waiting.

“What we’re saying to Canadian citizens is, wake up!” she said.

“We want our land back.”