In 33 years as a civilian employee with the Department of National Defence, Karen Lightbody says there would be a racist comment every month — at least.

“It was quite frequent,” she tells Nation to Nation. “Throughout my career I faced quite a bit of racism and discrimination.”

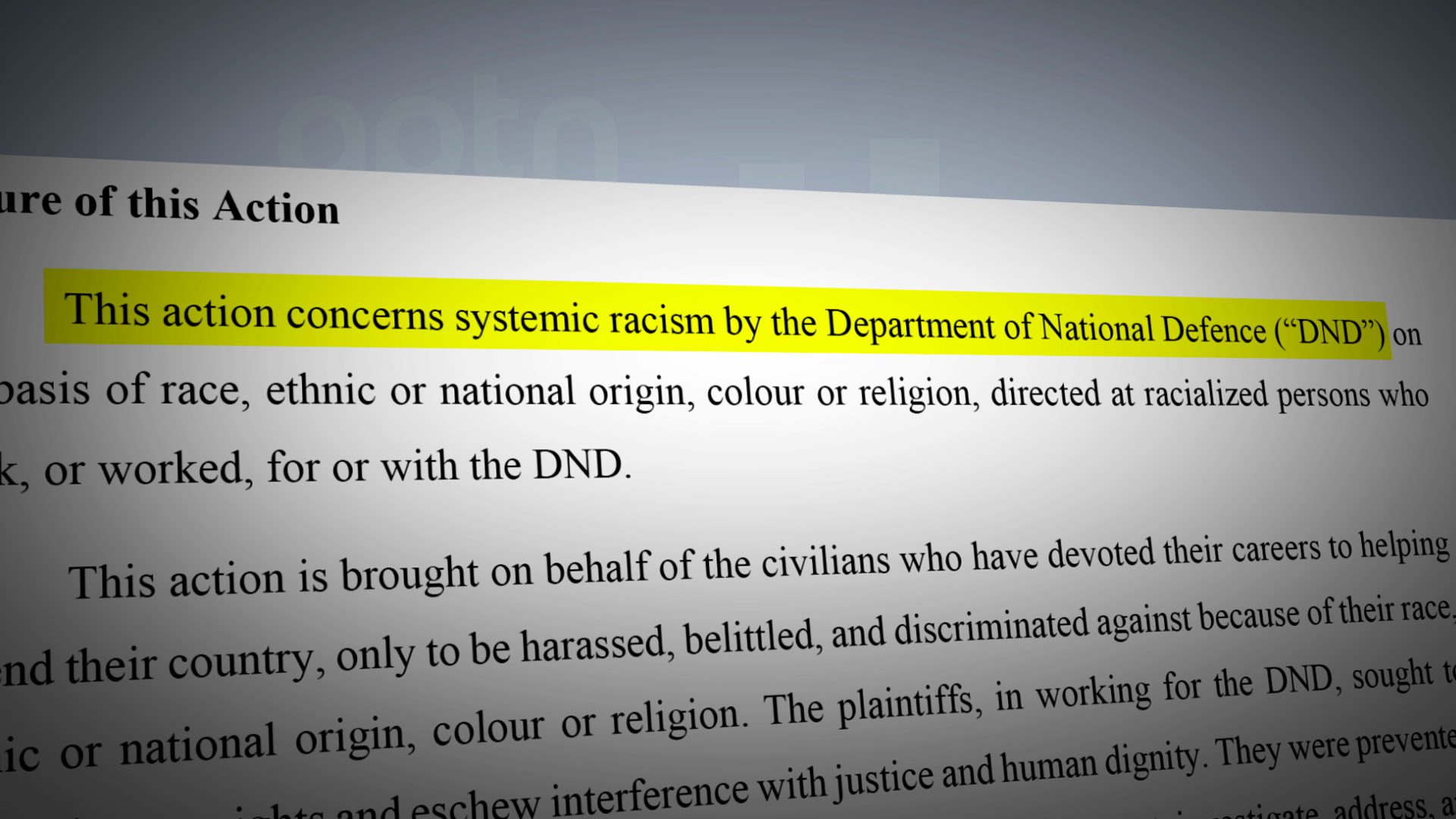

Lightbody, a member of Sayisi Dene First Nation in far northern Manitoba, is one of two lead plaintiffs in a proposed class-action lawsuit filed last October alleging widespread systemic racism in DND.

She joined the department in 1985 and later served as national civilian co-chair for the Defence Aboriginal Advisory Group. In an exclusive interview with N2N, the now-retired public servant explains why she felt compelled to put her name on the lawsuit.

“It’s not an organization that I can recommend to any of my family members to join right now,” she says. “Once there is change, then it would certainly be a nice place to say to my family, ‘Yes you should go and join the military or become a civilian member and work for the organization.’ But at this point I cannot say that.”

Her statement of claim describes a litany of racist slurs and derogatory comments Lightbody alleges she experienced throughout her career.

“The military captain of her unit stated about his assignment, ‘Not too bad, except for all those f—ing Indians’,” one allegation reads.

“When driving past a group of homeless people, a colleague told Ms. Lightbody, ‘Why don’t you go back to the reservation?’, gesturing towards the people,” reads another.

She says dealing with these comments day after day, year after year, left her struggling with suicidal ideation, impacted her mental health and forced her to take stress-related sick leave, though she says she’s now in a better place.

While the allegations haven’t been tested in court, the Canadian military and its associated bureaucracy have faced accusations of racism, misogyny and white supremacy for decades.

They’ve undergone probes, studies, scathing reports and similar lawsuits. Yet nothing seems to change. Why?

“The culture has not changed. This is something that has been in the culture since the military was created,” Lightbody says. “They need a huge culture shift.”

Her claim describes this culture as one of denial, cover-ups, obstruction and a laissez-faire attitude toward right-wing extremism, hate and more.

A public inquiry probing human rights atrocities committed by Canadian soldiers during a UN-backed peacekeeping mission to Somalia in 1993 blamed “rampant careerism.”

Lightbody, as the national co-chair, put pen to paper and authored a report on racism that was obtained by APTN News in 2017. She used that same word to describe the presence of racism back then: “rampant.”

“What I heard from other employees was that they had submitted complaints. They had gone through their chain of command to report these incidents,” she recalls. “However, a lot of them were brushed under or the perpetrators would be moved to another base. Quite often they would be promoted. I believe that they knew this was going on.”

Yet another advisory panel on racism, established by then-minister Harjit Sajjan in 2020, offered a similar negative verdict last week.

Read more:

Military involvement in racist, extremist activity ‘growing at an alarming rate’: report

The panel said racism and discrimination are empowered by the military’s colonialist culture, chronic abuse of power and a toxic, corrosive environment that is repulsing new recruits.

Retired sergeant Aronhia:nens Derek Montour joined the armed forces 1989. A year later, the military invaded his community of Kahnawake Mohawk Territory after warriors seized the Mercier Bridge during the Oka standoff.

“I recall experiences of racist slurs, racist remarks. One in particular has always stuck with me,” he says. A fellow soldier, someone he was ready to lay down his life with, said, “I hope we go in and kill all them savages.

“When you’re hearing that from the people who you’re supposed to be going into combat with — talking about your mom, your dad and you as savages — it really opens your eyes,” Montour recalls. “It made me think, am I doing the right thing?”

Montour soon quit the Canadian military and joined the Unites States Marines instead.

Thirty years later, he agreed to join the advisory panel and help compile this latest report after a conversation with Sajjan.

“Certainly, from the conversations we’ve had for the last year, these types of dialogues still exist,” Montour says. “Sometimes there’s an environment of permissiveness. Things are allowed to be said and not addressed.

“That’s really about leadership. Leadership really needs to step up at all levels to change that culture.”

And he had much more to say on the subject.

Watch both interviews above on N2N.