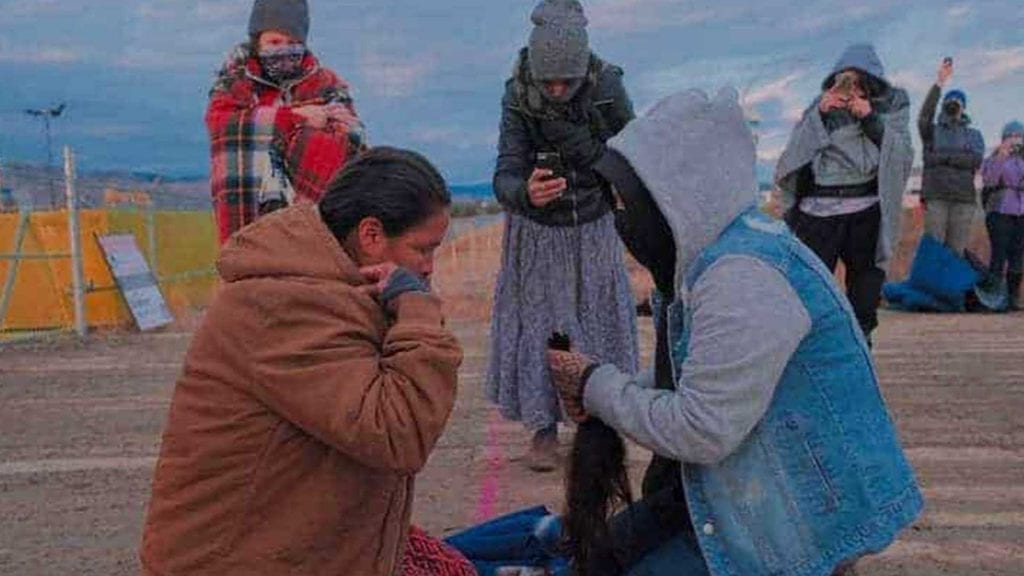

Miranda Dick, Secwépemc Matriarch, cut her hair during a hair cutting ceremony to begin mourning for the land. Her hair was cut by her sister who she trusted to care for her hair. Photo submitted by Miranda Dick.

Miranda Dick arrived armed with medicine to the gate of the proposed Trans Mountain pipeline expansion in Sqeq’petsin (Mission Flats, B.C.).

Dick says she reached into her pocket and felt her charcoal while she watched Trans Mountain pipeline workers spray paint a line across her Secwepemcul’ecw soil.

On that cold Oct. 17 day, Dick, a Secwépemc matriarch, was told that she could not cross the line, or she would be arrested.

Arrested under Canadian law, not Secwépemc law. She laid her ceremony blanket down on the ground and sent for scissors.

She sat down on the blanket, with her sister facing her. She carefully tied back her long black hair, her sister took it in her hands, and began to cut it off.

Secwépemc community members, mostly women, have been defending their lands, waters, lives and rights from the construction of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project since it was proposed in 2013.

Camps have been set up all along the proposed route from Edmonton to Burnaby, B.C.

The project, which the Canadian government bought for $4.5 billion in May, 2018, would triple the capacity of the existing pipeline.

The project includes 980 km of new pipeline, 193 km of reactivated pipeline, and four terminal expansions.

Dick is one of many Secwépemc community members who oppose the pipeline, which defenders of the land say was approved without adequate consultation or consent.

Primary concerns are the impacts on lands and waters, the violation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which the B.C. government has passed into legislation, and the violation of Secwépemc traditional law.

RCMP officers watched Dick cut off her hair. Whether or not they understood the significance of her actions didn’t matter, she says.

“This is what it has come down to. We’ve now gone to the depth of what we’re willing to endure, what we’re willing to go through to protect our water, our salmon and our children,” Dick tells IndigiNews while sitting at her kitchen table days later.

Dick says she cut off her hair to signify her own loss.

“Trans Mountain pipeline has no home on Secwépemc territory,” Dick says calmly, hands cupped around her tea cup.

RCMP arrested Dick and three others moments after her hair was cut, as matriarchs around her yelled “you are witnessing a genocide.”

The RCMP say in a press release, “demonstrators have the right to peaceful, lawful and safe protest and companies have a lawful right to complete their mandated work. The RCMP is working hard to protect both of these rights and ensure all parties and the public are kept safe.

“The four individuals who continue to interfere with operations at the site and were arrested for allegedly being in civil contempt of the Court Order.”

The group of four were released hours later. They are scheduled to appear in court in January 2021.

Okanagan/Shuswap Confederacy

Secwépemc traditional law predates Canadian law, and according to Dick, and the construction of the pipeline violates Secwépemc law.

“The Okanagan Shuswap Confederacy states, by their hereditary law, that no one can sign, cede, or surrender our territories,” Dick explains. “That’s for our future generations.”

The Okanagan Shuswap Confederacy represents a much older relationship and agreement between the two nations which upholds the laws of the land and nation members’ responsibilities to protect that land.

The controversial proposed Trans Mountain pipeline expansion would cross 518 km of Secwépemc territory. In June 2019, cabinet leaders approved construction after the project was highly criticized for lack of meaningful consultation with affected communities.

Secwépemc matriarchs hold strong that Canada must uphold Section 35 of the 1982 constitution, which affirms the inherent rights of Indigenous Peoples, one of which is access to clean water.

Dick emphasizes the difference between band councils’ authority and traditional Secwépemc law. The conflict of contrasting legal systems is an ongoing conversation in any situation involving industrial development, and the Canadian government’s attempt to consult and accommodate Indigenous leadership.

For Dick, the law is clear.

“We go back to the hereditary structure,” she says, adding that band councils are only responsible for what confines their reserve lands. “We push forward our hereditary chiefs and matriarchs, that is our natural law.”

“You can’t sign, cede or surrender territory, nobody can, not even me, not even my children can not do that,” Dick emphasizes.

‘We are rising’

As long as Trans Mountain workers and RCMP officers continue to push through pipeline construction in their traditional territory, Secwépemc Matriarchs will continue to hold ceremonies and defend their lands, Dick says.

She cut her hair and was arrested, not only to raise awareness on the ongoing conflict, but to raise consciousness, she adds.

“This is impacting our youth,” Dick says, as her eyes fill with tears. “We dedicated the canoe journey to the youth, because at that time we were having suicides and many attempts.”

The group keeps their Facebook page updated with the ongoing ceremonies and current events, they also run a website where they update folks on the events and continue to call for solidarity.

“We are the backbone of our nation, and we are rising,” Dicks sister, Gwa, says. “We are the matriarchs, and we are rising. Ain’t nobody going to stop us.”