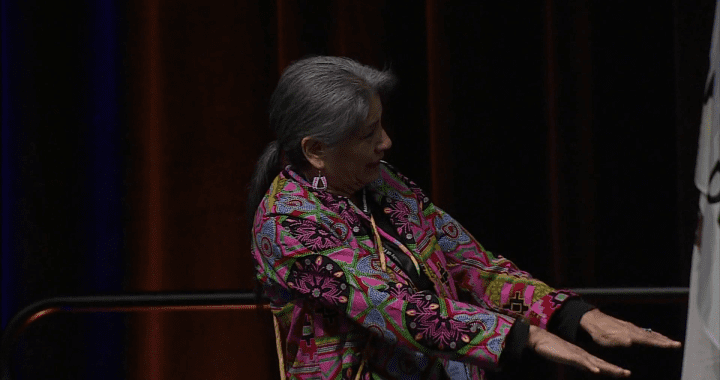

Happier times between an aunt and her niece, who recently ran away from a treatment program in Barrie, Ont., under the care of Weechi. Submitted photo.

When she answered the phone all she could hear is crying on the other end.

Then, through sobs, a voice of a young girl: “Auntie”.

She knew right away it was her 12-year-old niece.

“Oh my god. Baby, are you OK?”

“You need to come and get me right now. I can’t go back there. Don’t make me go back there,” said the young girl, calling from a Circle K convenience store in Barrie, Ont.

It was about 8:30 p.m. on Oct. 15, and the youth had run away from her treatment centre.

She was, according to her aunt, frantically running through the streets of Barrie – more than 1,600 kilometres from the child’s home community of Rainy River First Nations (RRFN), approximately 30 km west of Fort Frances, Ont.

“I’ve never been so scared. It was like my world was crashing around me and I’ve never felt so helpless,” said the aunt, adding she raised the child for the first five years of her life.

It was the first she had heard from the young girl since the end of July following a breakdown at the youth’s foster home with Weechi-it-te-win Family Services.

That foster home’s caregiver told APTN News the breakdown was the result of youth’s child welfare worker abruptly quitting her job on June 1.

She said the child has an attachment disorder, and can be difficult to deal with, but the worker was always available and able to keep the youth in check.

“When she quit I cried because she kept me in a good place with my foster child and when she quit it went downhill fast,” said the caregiver, adding the youth’s mother died on July 1, which didn’t help.

The mom never called her daughter.

“I had no support whatsoever and then the placement broke,” said the caregiver.

That was on July 31.

The worker was Shannon Stone.

Stone was the child in care worker at the community care program (CCP) for RRFN, which delivers on-the-ground child welfare care to children and youth in the system who are from RRFN. But it’s all done under the authority of Weechi-it-te-win, which is licensed, and mandated, by the province of Ontario.

It’s a devolved system, where the nations run operations of child welfare on-reserve, however Weechi’s executive director, Laurie Rose, is the legal guardian for every child. Rose works out of Weechi’s main office in Fort Frances.

RRFN is one of 10 nations under Weechi

Stone didn’t want to walk away from the child, or any of the other 17 children that were under her watch

“I loved my job and all my kids,” she said.

The CCP team had hit a rough patch and mostly due to interference from Coun. Leona McGinnis, who, at the time, was a board of director at Weechi.

Four people, including three from the CCP team, filed complaints against McGinnis in February. The other was the band manager, Jeremiah Windego.

Soon after the complaints were filed, Windego quit, as did Stone and child in care worker, Autumn Windego.

The team’s supervisor, Amanda Jourdain, is still on leave.

Four-month investigation confirms complaints against councillor

Their complaints launched a four-month investigation that confirmed these allegations against McGinnis: she was found to be in conflict of interest, making defamatory comments, failed to “maintain an environment free from harassment and discrimination” and crossed lines by interfering with “day-to-day” operations of the band manager according to the report obtained by APTN.

The investigation was done by a panel of two RRFN council members, who weren’t related to McGinnis, with the help of lawyer Julian Falconer.

In the end, the panel ordered for her immediate removal from the Weechi’s board of directors on July 31, the same day the foster home broke down with the runaway child in Barrie.

Stone told the panel she felt “threatened and targeted” by McGinnis.

One unnamed employee told the panel McGinnis is “hyper-vigilant and fears that any minor mistake or annoyance will result in backlash.”

The panel also spoke to another unidentified employee who said she is friends with McGinnis, and whom was picked by the councillor to speak about her.

The employee said the team had gone through several supervisors since Jourdain went on leave, but didn’t feel McGinnis was meddling with the CCP team.

A third unidentified employee, also picked by McGinnis, said they, as well, didn’t feel the councillor was interfering with the team.

The panel found the evidence of Autumn Windego to be convincing.

She is the first in four generations of her family to raise her own children, after growing up in care herself as a Crown ward.

Autumn Windego wouldn’t speak to the contents of the internal report, but said she got into child welfare to help people like herself.

“I was in lots of foster homes, some of them were good and some were really bad,” she said. “I know I can help them, because I have been there.”

But what happened in RRFN forced her to walk away, at least for now.

McGinnis gave a “blanket denial” to all allegations against her according to the panel’s findings.

Chief Robin McGinnis won’t comment on Leona McGinnis, who is his aunt, including whether she was removed from the board.

But he told the panel, he witnessed his aunt take “shots” at the former band manager.

In fact, the chief worried the band manager would quit.

He also had misgivings about his aunt being the community’s representative on Weechi’s board, considering she was also caregiver.

He also mentioned Leona McGinnis was fired as the supervisor of CCP team in 2018.

The internal investigation found the chief “had concern that she could use her seat at Weechi-it-te-win to lash out or discredit the CCP team or more specifically the CCP complainants.”

The chief said his aunt “still gets visibly upset sometimes about having been dismissed without cause 2.5 years ago from the position of CCP supervisor.”

His aunt would raise these matters at council meetings, he said.

“It’s like if she doesn’t like what is going on, she can use her council hat,” Robin McGinnis is quoted as saying.

He said while she has “lots of good ideas for the community” she had a desire to micromanage and “blurs the line between governance and administration.”

Robin McGinnis told the panel he was aware other staff were afraid of making their own complaints for fear of reprisal.

Related: First Nations child kept in care for two years after customary care agreement expired

Stone shared her resignation letter with APTN where in it she stressed the nation take note of what was happening.

“I hope you all take a good, long hard look at the program and it’s deficiencies and try to rectify the situation before you’re left without a team to manage the clients and caseloads. Trust me when I say the walls have ears and everyone talks, but you need to start asking the right questions to the clients, caregivers, community members and workers in order to understand and start building a better program for your community and its members,” Stone wrote.

“I will continue my fight for our families who are trapped in a broken system, but I will be fighting from different angle, one that is more loving and supportive, one which will clearly bring me more peace and joy.”

Jeremiah Windego told APTN he felt this matter was dealt with internally, but “if I don’t have anything nice to say I shouldn’t anything at all.”

Cashier confirms aunt’s story, recalls encounter

APTN tracked down the store clerk who tried to help the runaway youth in Barrie.

She described the youth coming into the store “all panicked” asking for a phone.

“She called someone … and she was crying a lot and asking them to take her back home,” said the store clerk. ” I guess they cut the call because she did not ask me to call them again.”

The youth instead called her aunt.

“She asked her to come get her. Then I talked to her aunt and she said that she ran away from family services … and she asked me to call the police so they can take her back. I called the police and they came in about 30 minutes and took her with them,” said the clerk

The clerk can’t forget that night and even followed up with the aunt to see how the child was doing the next day.

“She seemed so scared that she even hugged me and clearly she didn’t want to go back,” said the clerk.

The aunt, who lives approximately 350 km away in Sarnia, couldn’t come get her, because she was told not to be involved in the child’s care on Sept. 11 by Tracy Hoey, the acting supervisor of the RRFN CCP team.

“I need to let u know that [the youth’s] file is confidential … She may contact you in the near future but she is doing well and we need to let her continue on this journey. Please don’t take offence at this time, it’s not against you,” wrote Hoey in a text message.

The aunt responded she was concerned – especially since this was the first she was hearing from the CCP team despite calling their office for a month – and was seeking legal advice.

“Legal action doesn’t threaten me and if that’s what u need to make you feel better, that’s fine,” responded Hoey. “If we wanted you to be involved with her file we have let you know, but we as a team have signed a confidential agreement. That’s how we stand.”

There’s another reason they won’t let the aunt be part of the youth’s care – the CCP doesn’t consider her to be biological family.

The youth’s birth certificate lists the aunt’s brother as the father, but a paternity test years later allegedly confirmed the biological father to be someone else.

APTN has not seen the results of the test, however two people confirmed it.

The aunt said the child also didn’t have contact with her biological mom, who signed her over to the aunt shortly after birth. A death in the family led to the aunt’s home breaking down when she was about five-years-old. The aunt has been fighting to see her since.

Then for a year they spoke every Sunday until the placement broke down.

Leona McGinnis didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment over a two-week period, nor did Hoey respond to text messages to her work cellphone.