Pamela Poitras-Heinrichs has spent the last few years retracing a fractured history.

Through the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association’s Indigenous Veterans Project, she and a team of volunteers have identified more than 100 Indigenous soldiers who served in the Battle of Hong Kong.

“Rather than just the Association saying, ‘Here’s our Indigenous soldiers’, I wanted to see how Indigenous families would benefit from it,” Poitras-Heinrichs said during an APTN News interview.

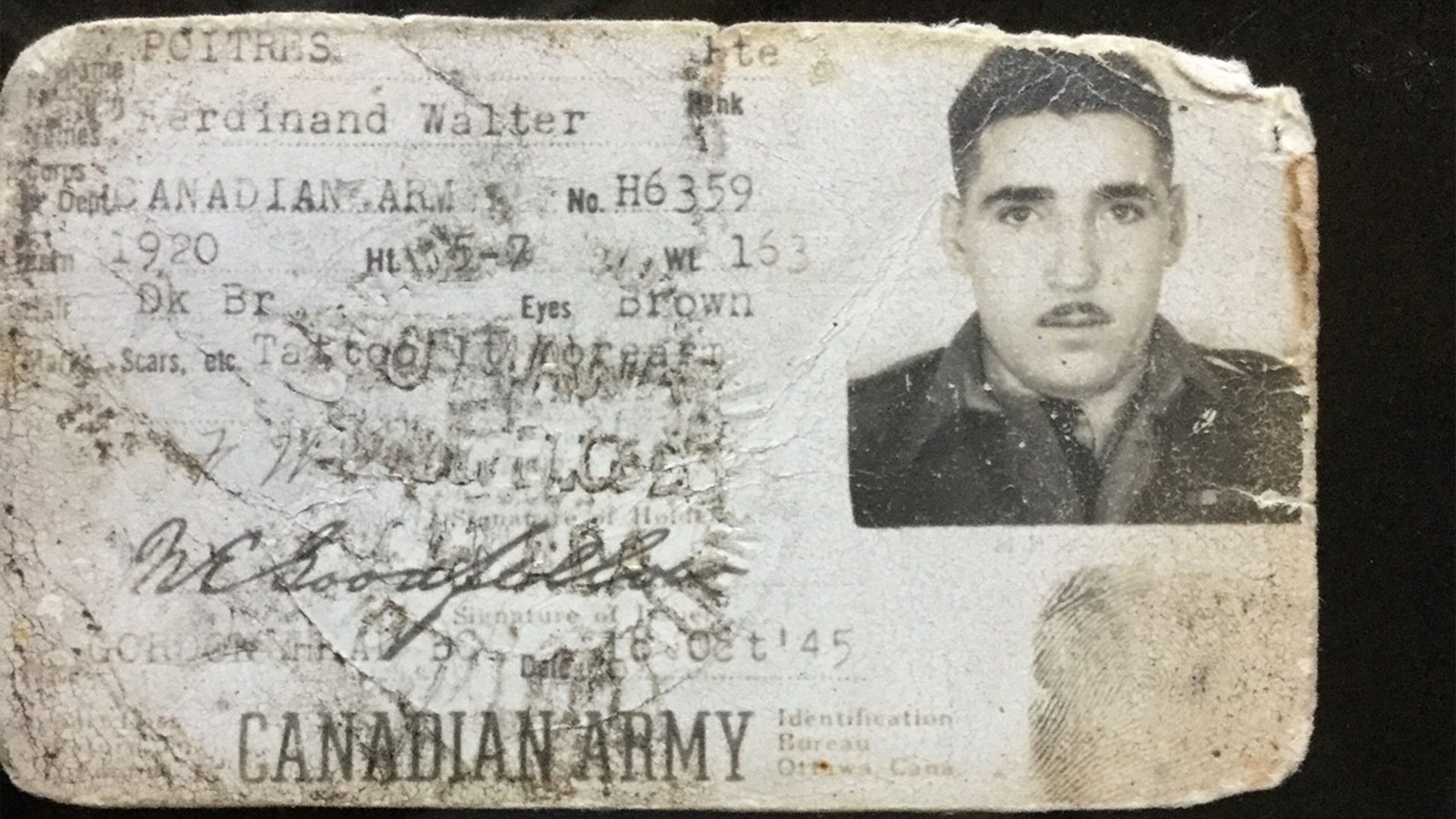

Her father, Ferdinand Poitras, was a Red River Métis veteran from Winnipeg. However, like many Métis veterans, he concealed his Indigeneity.

In fact, when he enlisted, there wasn’t a ‘Métis’ category: soldiers were identified as First Nations or by European ethnicities.

“The project is special to me in that regard, too, because I’m sure there are other families that were the same,” she said. “We can now take pride in that.”

The Battle of Hong Kong

Ferdinand Poitras enlisted with the Winnipeg Grenadiers in 1939.

He was among 1,975 military personnel that formed the Canadian contingent of the Battle of Hong Kong – known as the ‘C’ force.

Growing up in the former RM of St. Vital, Poitras left school at age 12. After a series of precarious manual labour stints, joining the forces meant steady work.

The Grenadiers were sent to Jamaica for 14 months on garrison duty, and briefly returned to Canada in August 1941. In November 1941, the regiment arrived on the harbour of Kowloon, Hong Kong.

“Britain asked Canada to send regiments just in case Japan attacked the British colony of Hong Kong,” said Poitras-Heinrichs said. “It was apparently never dreamt that that would happen.”

But it happened.

“Their army vehicles didn’t reach them, all kinds of supplies didn’t reach them, and they were greatly outnumbered by the Japanese who were battle-hardened troops,” said Poitras-Heinrichs. “They had to surrender Christmas Day 1941, and any that did survive the battle became prisoners of war (PoWs).”

Japanese PoW camp

Canada lost 290 troops in that battle. For the next three-and-a-half years, Poitras lived and worked in a Japanese PoW camp in Hong Kong.

“My dad was prisoner Number 110, and he could still say that number in Japanese right up until his 80s,” Poitras-Heinrichs recalled.

While he seldom spoke of his time as a PoW, his daughter said the few stories he shared reflected the harsh conditions of the camps.

“He was made to stand for hours holding pails of water in each hand with his arms out,” she said. “If he started to drop them, he was beat.”

In total, 264 Canadian PoWs died in the camps, usually of illness or starvation.

In 1945, the Canadians were liberated after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced Japan to surrender.

However, when Poitras and other Métis veterans returned to Canada, they faced another reality.

Poitras’ exit interview, dated March 5, 1946, described slim prospects.

“This is the part I found interesting,” Poitras-Heinrichs said, “‘his background and education place him in the general labourer class.’ So, it wasn’t even thought that they could go on and do anything more.”

Poitras died in 2008 at the age of 87.

Reclaiming Métis pride

While some Métis veterans hid their Indigenous identities, others, like Manitoba Métis Federation Minister John Fleury, wore theirs with pride.

But their pride wasn’t always accepted by Canadian institutions.

“They either asked you to identify as English or French,” said Fleury of enlisting in the military. “I had an issue with that, so I would cross it out and say I was Métis, and they would say that’s unacceptable, you have to respond with English or French.”

At the same time, Fleury understood why some Métis suppressed their Indigeneity.

“If people could just assimilate into the non-Indigenous society, then they would – for the sake of advancement, protection of their families,” he said.

Growing up in Winnipeg, Poitras-Heinrichs said her father never spoke of being Métis. He told his children his family spoke “Parisian French”, which his daughter would later learn was actually Michif, a combination of Cree and French.

She began reconnecting with her traditions at 19 years old – the same age her father was when he enlisted.

During an afternoon visit to the St. Boniface Museum, she noticed a ‘Poitras’ in a portrait of the extended family of Louis Riel – the first Métis leader. The curator recommended she consult the St. Boniface Historical Society, which stores Manitoba’s Métis archives.

“I found out that Louis Riel’s sister’s husband was my grandpa’s uncle,” she said. “The Poitras and Riel families were very closely connected.”

In October, Poitras-Heinrichs had a booth on the Indigenous Hong Kong Veterans Project at the Manitoba Métis Federation Annual General Assembly.

“We had people walk by and say, ‘That’s my great grandfather’,” she said. “There were some other families that came by that had no idea about the association or about the project and what we were doing.

“They were literally in tears at our booth, so moved and grateful for what we’re doing for their family member.”