Diane Bigeagle holds a poster of her missing daughter Danita. Submitted photo.

A Regina lawyer continued his assault Tuesday on Canada and its national police force’s poor record of investigating and solving cases of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG).

“The government has been aware of this issue for decades and done nothing about it,” said Tony Merchant on the second day of a five-day Federal Court hearing in Regina this week.

Merchant is representing Dianne Bigeagle whose youngest daughter Danita Faith Bigeagle disappeared from Regina in 2007. RCMP took over the missing persons file, court heard, after it was first opened by the Regina Police Service.

Dianne was in the courtroom briefly Tuesday after spending the full day there Monday.

Lawyers for Canada are scheduled to begin their counter-arguments Wednesday.

Dianne launched the proposed class-action lawsuit in 2018 against Canada on behalf of families and their communities. She is seeking $600 million in damages for what Merchant described as “systemic negligence.”

In his argument to Justice Glennys McVeigh in favour of certifying the lawsuit, he said there was no shortage of problems in the relationship between RCMP and Indigenous peoples. And no shortage of evidence as to why.

“Just because Canada doesn’t recognize an issue doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist,” Merchant said.

“We’re only here with one client but we’ve been contacted by 50, 60 others.”

Like hundreds of other victims, Danita’s case remains unsolved. The number of cases nationally – believed to be between 1,200 and more than 4,000 – were examined by a national inquiry between 2016-18, with Merchant using many of its findings about “negligent police investigations” in his argument.

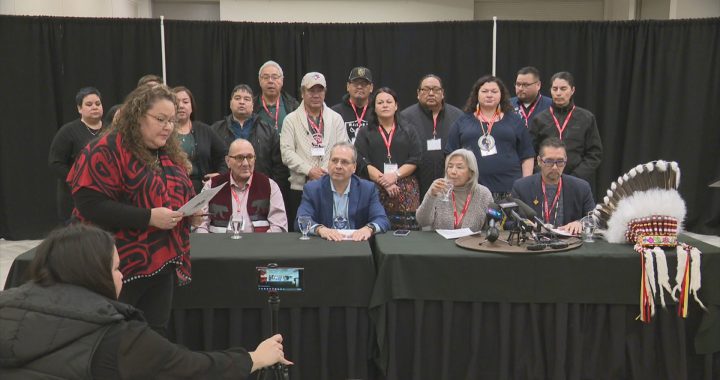

Tony Merchant (right) and an associate bring files into the court. Kathleen Martens photo

He also cited “like-minded” reports by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International into the ongoing violence perpetuated against Indigenous women and girls, as evidence of a chronic, discriminatory phenomenon police have failed to address.

“They spent time digging down into the stereotypical thinking and behaviour of police,” he said of the various reports’ researchers and authors.

Merchant told court his team experienced the same problems the inquiry did when it came to obtaining information from the RCMP. He said the lawyers requested results of two of the RCMP’s MMIWG task forces – programs Project Devote in Manitoba and Project E-Pana in British Columbia.

But despite being proud of the initiatives no information was shared with the lawyers, Merchant said, nor were the task forces expanded nationally.

“To know of something better and not do it and harm the results from not doing it is the definition of negligence,” he said.

“The response seemed to have been, ‘Well, we’ll wait for a national direction’ or it just didn’t catch on.”

READ MORE: Dianne Bigeagle v HMTQ statement of claim

Merchant also noted the national inquiry recommended compensation for families. It’s a form of closure, he argued, for the victims’ children and grandchildren when investigations don’t provide results.

His client testified before the inquiry’s commissioners during their Saskatoon hearing, but did so privately.

Meanwhile, this isn’t the first class-action lawsuit to allege that colonization and discrimination have harmed Indigenous peoples. Merchant said those factors were accepted when Canada settled the Indian Residential Schools and ‘60s Scoop lawsuits.

The case continues Wednesday in Regina.