It’s a new kind of nuclear reactor that the federal government is putting up $50.5 million in development money for, but some Indigenous leaders are already speaking out against it.

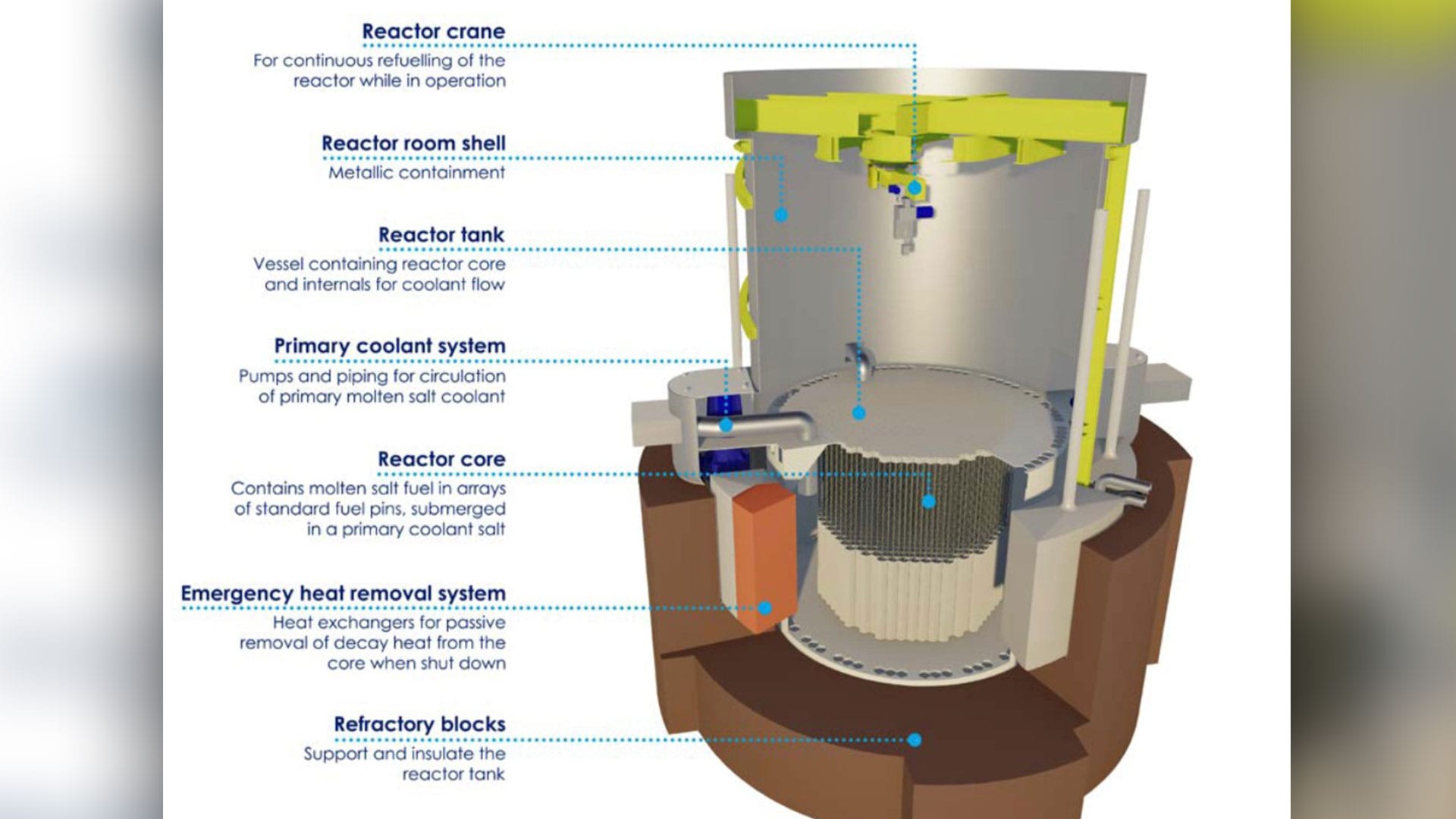

Moltex Energy Canada is getting the tax-dollar investment to develop what the nuclear industry calls a “small modular reactor” or SMR – which is generally considered to be a reactor with a power output of 300 megawatts or less.

The Moltex SMR design is to be developed at New Brunswick Power’s Point LePreau Nuclear Generating Station, which is on the north shore of the Bay of Fundy and in Peskotomuhkati traditional territory.

ARC Clean Energy Canada is another operation also set to develop an SMR at the Point LePreau site. It was announced in February that ARC would get $20 million from the New Brunswick government if the company can raise $30 million of its own cash.

Hugh Akagi is Chief of Peskotomuhkati Nation and has concerns about more nuclear development in the aging facility.

“Well, I don’t feel very good about it, to be honest,” says Akagi. “You paid that money if you pay tax on anything in this country, you’ve just made a donation to Moltex. If you’re not concerned about $50 million being turned over to a corporation for a technology that does not exist – I hope you heard me correctly on that.”

The federal government has taken a shine to the idea of SMRs and Minister of Natural Resources Seamus O’Regan is on the record as saying “We have not seen a model where we can get to net-zero emissions by 2050 without nuclear.”

Under the Small Modular Reactor Action Plan, the federal government is pushing for SMRs to be developed and deployed to power remote industrial operations as well as northern communities.

Three streams of government-supported SMR developments are underway at two sites in Ontario as well as at Point LePreau.

As well, the governments of New Brunswick, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta have all signed a memorandum of understanding pledging their support for SMR development.

Akagi says he hasn’t been formally consulted – but has been to a presentations put on by NB Power about the SMR project.

He says he is unlikely he’ll ever give it his support.

“Until I can have an assurance that the impact on the future is zero,” says Akagi, “I don’t want to 100 years, 200 years is still seven generations. I want zero impact.”

But Moltex Energy Canada CEO Rory O’Sullivan says his company’s technology will ultimately reduce environmental impact, by recycling spent nuclear fuel from full scale reactors.

“Instead of putting it in the ground where it’ll be radioactive for very long periods, we can reuse it as fuel to create more clean energy from what was waste,” says O’Sullivan. “We can’t get rid of the waste altogether. But the aim is to get rid, to get it down to about a thousandth of volume of the original long-lived radioactivity.”

O’Sullivan admits to formerly seeing nuclear as too much of a problem to be a viable solution in the climate crisis.

“When I graduated as a mechanical engineer I saw that nuclear is potentially as too expensive, has the waste issue, has a potential safety issue,” says O’Sullivan. “Well, actually, with these innovative new designs, you can potentially have nuclear power that is lower cost, cheaper than fossil fuels – you can get much safer solution using innovation and you can potentially deal with the waste.”

Gordon Edwards, one of Canada’s most prominent nuclear critics, isn’t buying that argument.

Edwards is president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility and notes the Moltex SMR plan involves a preliminary step of dissolving spent nuclear fuel in molten salt, and there lies an issue, he believes.

“What happens when you dissolve the solid fuel in a liquid, in this molten salt – then all of these radioactive materials are released into the liquid,” says Edwards, “and it becomes more dangerous to contain them because a solid material is much easier to contain than a liquid or gaseous material.”

Edwards also works on a radioactive task force with the Anishinabek Nation and the Iroquois Caucus.

And as he sees it, small modular reactors could make it harder for Indigenous communities to say no to the deep geological repositories [DGRs] being pitched to Indigenous communities as a supposedly safe way for Canada’s nuclear industry to entomb highly radioactive waste for hundreds of thousands of years.

“We don’t accept the small modular reactors because we know that it’s just a way of implicating us so that we can then have less of an argument against being radioactive waste dumps,” says Edwards. “If we accept small modular reactors into our communities, how can we then turn around and say we don’t want to keep the radioactive waste? It would just put us in an impossible position.”

Edwards and other nuclear critics such as Akagi recently participated in an online webinar focused on concerns around nuclear development at Point LePreau.

And those adding their voices to the critical side of the ledger on nuclear development at Point LePreau include Jenica Atwin – the Green Party’s MP for Fredricton, and Wolastoq Grand Council Chief Ron Tremblay – who issued a Resolution calling for nuclear development to be halted.

Atwin put out a release in April calling Canadian nuclear policies “profoundly misguided.”

“My basic premise is that the government needs to be more responsible in the information that they’re sharing just in general to talk about the risks that exist alongside whatever benefits they’re kind of touting,” says Atwin. “And right now, we’re only hearing that it’s the greatest option. This is how we fight climate change. It is clean, it’s cheap energy. And I have to disagree.”

If all goes to according to the Moltex plan, its SMR could be operable by about 2030.