Trina Roache

APTN National News

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal has ordered for the full implementation of Jordan’s Principle to ensure equal healthcare for Indigenous children in a decision released Tuesday.

The order was part of the long-awaited ruling released Tuesday that detailed how Canada discriminates against Indigenous people in its policies and funding of child welfare on-reserve.

The goal of Jordan’s Principle is to ensure Indigenous children on-reserve have equal access to healthcare.

“(Indigenous Affairs) is also ordered to cease applying its narrow definition of Jordan’s Principle and to take measures to immediately implement the full meaning and scope of Jordan’s principle,” the tribunal said in its 182-page. “More than just funding, there is a need to refocus the policy of the program to respect human rights principles and sound social work practice.”

Who pays for health services on-reserve – the province, Indigenous and Northern Affairs, or Health Canada – can be complicated. Jordan’s Principle dictates care for the child first and fight over who pays later.

Despite the House of Commons unanimously adopting Jordan’s Principle in 2007, Indigenous Affairs went on to define the principle so narrowly, that it said no cases existed.

The human rights tribunal didn’t agree.

“Such an approach defeats the purpose of Jordan’s Principle and results in service gaps, delays and denials for First Nations children on reserve,” the decision said.

Jordan’s Principle is named after Jordan River Anderson, a young boy with severe special needs from Manitoba’s remote Norway House Cree Nation. He died in hospital while the province and federal government fought over his care. He never got to see his home.

Ottawa came up with a complicated definition. It only applied the principle to situations in which there was a dispute between the federal government and the province over who should pay for a service needed by a child on-reserve with multiple disabilities requiring multiple health services.

“It is Health Canada’s and AANDC’s narrow interpretation of Jordan’s Principle that results in there being no cases meeting the criteria for Jordan’s Principle,” the tribunal ruled. “Jordan’s Principle is meant to apply to all First Nations children. There are many other First Nations children without multiple disabilities who require services, including child and family services. Having to put a child in care in order to access those services, when those services are available to all other Canadians is one of the main reasons this Complaint was made.”

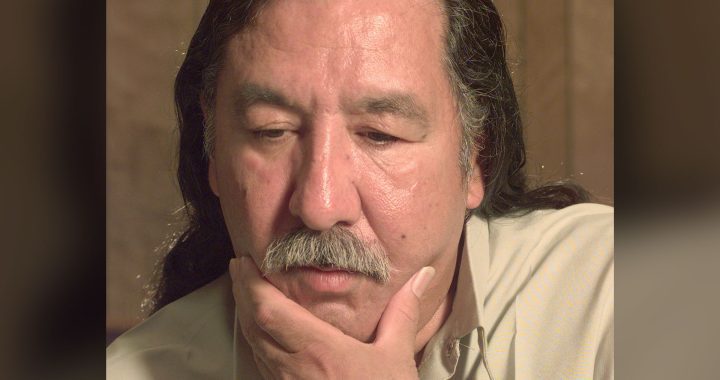

Tribunal panel members heard hundreds of hours of testimony over 76 days of hearings. Thousands of documents were submitted in a fight that began in 2007 when Cindy Blackstock, a First Nations’ child welfare advocate along with Assembly of First Nations, filed a human rights complaint.

The panel found Canada’s position “unreasonable, unconvincing and not supported by the preponderance of evidence in this case.”

In an interview last December, Blackstock said documents show a federal bureaucracy working to protect politicians over the needs of Indigenous children.

“It’s very clear to me they completely didn’t get it,” Blackstock said at the time. “Or even if they did get it, they felt the moral course was to deny children services and I think that’s unconscionable. There shouldn’t be more red tape for them to jump, there shouldn’t be longer waits. They shouldn’t be denied services because they’re First Nations’ children.”

Three years ago, Mi’kmaw woman Maurina Beadle, took the federal government to court for not providing equal healthcare services for her son Jeremy Meawasige, who has special needs.

When Beadle had a stroke in 2010, her band the Pictou Landing First Nation in Nova Scotia, picked up the tab for Jeremy’s extra home care. But argued that it was a cost Ottawa should cover. And not doing so made it a case of Jordan’s Principle.

The courts agreed. Beadle won her case.

A year later, Ottawa appealed. And an internal federal document puts that decision squarely at the feet of then Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt, who was defeated in October’s election.

“Minister Valcourt, the federal lead for Jordan’s Principle, decided to have the Crown appeal the decision on May 6, 2013, on the principle that the Judge erred in his interpretation of JP,” noted a memo labelled “secret.”

Ottawa had consistently argued no cases of Jordan’s Principle existed.

Emails between federal officials at Health Canada paint a different picture.

“There will likely be more cases coming forward so we will definitely need a good tracking system,” the documents said.

Blackstock pointed to a April 15, 2013 document, which summarizes a call between officials with Health Canada and Aboriginal and Northern Affairs discussing how to narrow the impact of Beadle’s court victory.

The memo detailed how two bureaucrats decided the Pictou Landing case “will be labelled as a JP case, that way it can be treated as an isolated case and the interim remedy can be limited to this case alone.”

Blackstock said that document showed how the Harper government saw Jordan’s Principle as a way of limiting the services for kids.

A lot has changed since these emails and briefing notes were volleyed back and forth between bureaucrats. The Liberals now form a majority government.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has issued its report. Recommendation Number 3: “We call upon all levels of government to fully implement Jordan’s Principle.”

In its decision, the tribunal left the remedies – how government should fix this problem – for a later date. Reaction from the Liberal Government is still to come.

Blackstock and the Assembly of First Nations will hold a press conference later Tuesday.

Back in December, when Blackstock still had her fingers crossed over the tribunal decision, she said whatever changes happen, it’s not just about more money for child welfare and health services for First Nations.

“The bureaucracy is still in place,” said Blackstock. “And their particular goal appears to be to have protected the minister and they didn’t make the effort to really ensure that children were the focal point of benefitting from federal services. I’m hoping we see that change.

For Blackstock, it’s a matter of making sure that memo makes it through the red tape.

“I’m hoping the federal government immediately instructs the bureaucrats to make sure these changes reach down into the levels of kids,” she said.