Ontario Premier Doug Ford.

The Ontario government is demanding $300 from APTN News to complete a Freedom of Information Act (FOI) request to disclose the number of children that have died, or seriously injured, in the child welfare system since the novel coronavirus was declared a pandemic on Mar. 11.

This is the latest development in what’s been months of stalling by the province, beginning with Minister Jill Dunlop’s office and particularly her spokeswoman, Hannah Anderson.

Experts told APTN the government’s action “make no sense” because it can easily provide this information without an FOI.

APTN’s own reporting on deaths in care over the last three years confirms this.

Yet, as of today, APTN still can’t say how many kids have died in foster or group homes, which have been in lockdown for months, because we haven’t paid the money.

It was Anderson who first told APTN on April 23 that asking for the number of deaths and serious bodily injuries in care was too complex and she believed we needed to file an FOI.

APTN pointed her to where the data could be found – some of which should practically land on Dunlop’s desk in what’s historically been called “contentious issues report”, that includes serious urgent matters, such as deaths, that as minister she should be aware of.

But we also told Anderson the ministry of children, community and social services (MCCSS) also has a database of this information. The database is made up of what’s known as “serious occurrence reports” (SOR) that individual child welfare agencies are required to file to the ministry for such things as a child dying, suffering serious bodily harm, use of restraints, self harming and missing persons.

Plus, APTN told her back in April, the MCCSS FOI office was closed due to the pandemic, like many government offices across the country.

Anderson said she would be in touch.

The following day APTN received a response, but not from Anderson, who passed us back over to the ministry.

“This information request is beyond the scope of a traditional media response, and should be directed to ministry’s Freedom of Information team. The team can be reached at 416-327-0301,” said Trell Huether, spokesman for MCCSS.

Even on the best of days, Ontario has an archaic FOI process, which requires a $5 cheque or money order that has to be mailed through post – not email or fax or any other modern-day convenience.

But in the midst of a pandemic there was no one in the office to receive the cheque to begin a new request.

APTN was aware of this because we were privy to another battle with the same FOI department that wasn’t processing ongoing requests back in late April, again, because it couldn’t accept payment.

Which we posted to Twitter on April 29.

There's nobody in the office to accept new FOI requests or process payments that can only sent via cheque or money order. @HannahhRA should have known this when declining to provide the information. https://t.co/99kp2iJEIS

— Kenneth Jackson (@afixedaddress) April 29, 2020

At about the same time APTN wrote Heather Hogarth-Griffin, one of the MCCSS FOI analysts, asking what the time-frame was for new requests, considering everything.

Her boss, Cate Parker, a senior manager, responded about two hours later.

Suddenly there was a new process that wasn’t there earlier that same day.

“While we are currently unable to receive access requests by mail, we are happy to receive a scanned copies of: your original request(s), payment (cheque or money order made payable to the Minister of Finance),” wrote Parker.

In a short email exchange with Parker, APTN said it was looking for deaths and serious bodily harm and questioned how they could access their database of this information if no one was in the office.

“Once we receive your precise request and proof of payment, we will work with the program area in question to access the information. Staff continue to have access to databases and business tools while they are working remotely,” said Parker.

APTN followed this new policy and submitted two requests – the deaths and bodily harm as one request and a separate one for SORs relating to a certain agency for a different story.

Then waited.

A week went by APTN received a telephone call from Peter Cavell, the FOI analyst assigned to the deaths/bodily harm request, and someone APTN previously dealt with.

Cavell called to clarify our request. Did we want in care and out of care numbers? Did we want institutional numbers, like in jail, as well?

APTN wanted all of it. This was a mistake and the second we made.

The first was asking in our original request, if possible, to provide a breakdown by race, such as how many of these kids dying were Indigenous.

That created a delay of 10 days, as Cavell said he couldn’t find data broken down by race, something the province doesn’t collect, which APTN already knew, as should have Cavell based on previous discussions.

Yet, it played a big part in slowing the request.

So we told Cavell just provide the two numbers we first asked Dunlop’s office for:

Deaths.

Serious bodily harm.

Just the numbers.

“That is fairly easy for us to pull,” said Cavell, in a telephone call on May 13.

“We can definitely get that for you a lot faster.”

A day before that call with Cavell, APTN received the cost estimate on the other request.

APTN asked if we could also scan a cheque and email.

“Our access to mail has resumed and we will be accepting payment through the mail as is our usual practice. We will be able to release files through secure email delivery,” said Hogarth-Griffin, in a May 13 email.

“Please also be advised that we have not yet received your initial application fee. Hopefully it is only delayed in the mail, but we do need to receive it before we can release a final decision on this request.”

Up to this point no one had said to mail a cheque. APTN had followed their new policy, as outlined in the April 29 email from Parker.

APTN then wrote Cavell: “It’s been over a week since we last spoke on the phone where you said you could quickly finish this request. These are children in care during a pandemic. Certainly there is a bit of urgency.

“Can you please advise what is happening? My other request was emailed to me. I need to mail in cheques and would like to do so at once.”

Three days later Cavell responded the act allows the ministry 30 days to respond.

“While we always strive to respond earlier when we can, FOI requests are complex and time is often required to make sure we are providing a response that is as accurate and thorough as possible,” wrote Cavell in an email on May 25.

“As well, please note that the ministry still has not received the application fee that you said was mailed on April 30th. In the absence of an application fee, an access request is not considered complete and the ministry is not able to provide a decision.”

APTN responded: “Whether you want to take the full time to process what you told me two weeks ago would be quick is really up to you. It’s for deaths and hurt kids in care. That’s not my call. But read below. I did what was asked.”

An email chain between APTN and Parker clearly showed she never said to mail a cheque, but scan a cheque.

Five days later, and 30 days exactly after APTN first filed the FOI requests, Parker wrote saying the ministry wouldn’t process the request without a physical $5 cheque in their hands.

“As a courtesy, the ministry has continued and will continue to take steps to process both of your access requests. However, until your application fees have been received, neither of these requests can be considered complete and the ministry is not able to issue a final decision,” wrote Parker.

The process APTN followed allowed it to receive a cost estimate on one request but not the other?

It didn’t make sense.

Either way, APTN was left with no option other than to courier the fees from Ottawa to the ministry in Toronto.

Canada Post confirmed the package was delivered June 8.

Then a week went by.

On June 15 APTN wrote Hogarth-Griffin, Cavell and Parker: “You have had the cheques now for a week as of today. Can you please advise what you are doing with the deaths and serious injuries? What’s the hold up?”

Cavell fired off a letter confirming receipt of the cheque saying he had started the 30-day clock over again.

Hogarth-Griffin replied by email they didn’t actually receive the cheques until June 12, five days after Canada Post had said.

Wasn’t there people in the office now?

“Our postal box is managed by Government Mail Services who accept mail and packages on our behalf and process them according to their safety protocols. Normally we receive the mail from them in only a day or two, but with the current ongoing pandemic there may be unavoidable delays to when we receive the mail,” wrote Hogarth-Griffin.

APTN responded: “I suppose that is why your office created the policy of being able to scan cheques, eh?”

On June 30 APTN received two letters from Parker.

They estimated it was going to cost $300 to pull the deaths and serious injuries and gave APTN 30 days to pay half to keep the request going.

“Due to the broad scope of the request, the final fee cannot be determined until all of the responsive records have been collected and processed. Based on our preliminary search, I have calculated an estimated final fee. However, as this figure is an estimate, the final fee may be more or less than this amount depending on the number of records located and the time required to undertake the search and review,” said Parker.

This is the “broad scope” request: “The number of unique child/youth Serious Occurrence Reports for deaths and serious injuries between March 11, 2020 to April 30, 2020.”

And as for the request Hogarth-Griffin determined would take three hours to complete for $105?

Parker now denied that request saying the child welfare agency APTN was focusing on was too small and kids may be identified.

APTN is set to appeal that decision with the Ontario’s information and privacy commissioner.

Ontario’s former child advocate, Irwin Elman, who saw his office get closed by the Ford government in early 2019, said the province needs to stop treating information as its property.

He said even if someone had to manually look through SOR reports on deaths and serious injuries by hand it wouldn’t take long.

“It might take them a few hours tops,” said Elman, adding the ministry should have just provided it in the first place.

Of course, there are two other places where this information is tracked.

The coroner’s office has a longstanding policy where if a child or youth in care, or one who had contact with an agency within 12 months of their death, an agency must report it to the coroner.

Often this data is released through the chief coroner’s annual paediatric death review committee report.

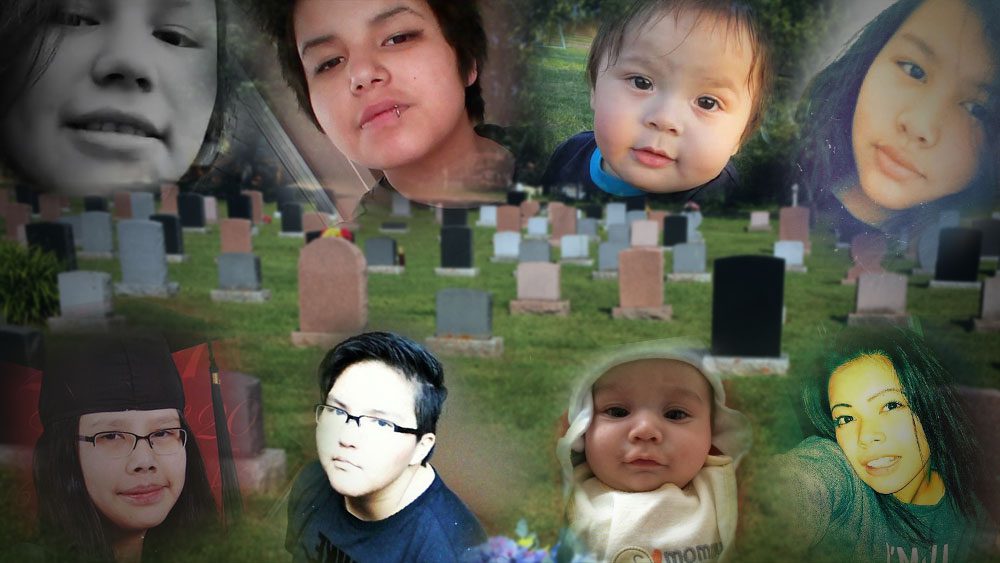

APTN previously used these reports to determine 102 Indigenous children connected to the child welfare system died in the five years between 2013 to 2017.

APTN has been asking the coroner since January for the 2018 and 2019 reports, or at the very least the deaths, but kept being told it would take a couple more weeks. This went on until the pandemic began and now the office has stopped responding to our emails.

Child welfare agencies used to have to notify Elman’s former office of deaths and serious injuries, which shifted over to the ombudsman’s office upon the advocate’s closure.

The ombudsman also declined to give APTN the data without providing a reason.

“The coroner, ministry, minister and ombudsman all have the information and data,” said Elman. “The coroner has the ability with the touch of a key board to find numbers and data. It is not rocket science.”

One person who knows about the SOR database and what the data means is Dr. Kim Snow, a professor at Ryerson University in Toronto and a leading expert on child welfare.

In fact, it was Snow’s work in 2017 with the former child advocate’s office that sparked the creation of the database.

Snow reviewed 4,436 serious occurrence reports over a three-month period finding half of the reports related to children and youth being physically restrained in residential care, like foster and groups homes, as well as jails.

“Someone should be able to go into the database and get that information within minutes,” she said.

“It makes no sense to me. This is a request that should available to anyone in the public. It should generate a response within a couple weeks at the most. You are just asking for the number.”

“All they are doing is adding up columns. It really is that quick.”

During Snow’s work reviewing the serious occurrence reports she noticed a phrase used for certain children that died in care: “Death as Expected”.

It was all that was written on the SOR about the child’s death and usually meant the child had a serious illness.

It was also the title of our look into 102 deaths last September.