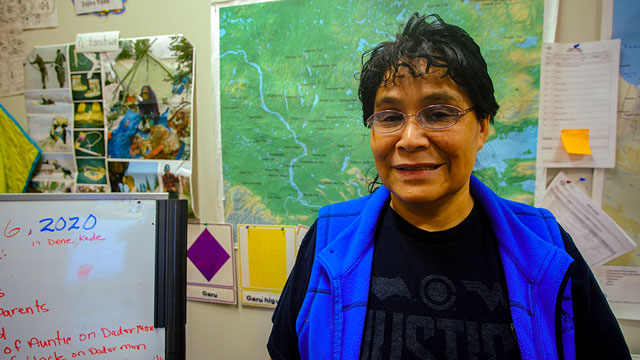

Linda Manuel dreams of a classroom in the NWT where she can teach Sahtúot’ı̨nę Yatı̨́ the way she wants to – in an immersive space, large enough to entertain Elders, assemble a tipi and incorporate cooking.

“With the language the child needs to concentrate but can hear people talking in English. He or she cannot concentrate. You can hear what the other students are doing because there are no walls,” Manuel said.

It’s a far cry from current conditions, a cramped corner classroom lined with Rubbermaid totes and a blanket in place of a door.

“The pipes are broken today or it’s something to do with the sewage and water. There is always something wrong with this building,” she said.

The students and staff must rely on one washroom today, with the girl’s being out of commission.

On this day, the girl’s washroom and kitchen sink are out of commission.

In 2018-2019 the school closed for days on end because of septic issues.

This is just part of a larger concern around access to clean water. Colville Lake has been under a 16-year boil water advisory since 2004.

In 2008, APTN News reported Colville Lake School had been without running water for eight years.

Students at the time were using a slop bucket as a toilet.

All the while, Behdzi Ahda First Nation, in Colville Lake has been requesting a new facility for the better part of a decade.

The school is located in a one-room log house with a second building adjacent called the “small school.”

The main building serves kindergarten to grade 12, but this year the “small school” houses junior kindergarten to Grade 4.

K’áhbamį́túé (Colville Lake), is a traditional community in the Shatu accessible only by ice road and plane. Roughly one-third (40) of the community’s 150 residents are school-aged children. But numbers are dwindling as parents send their kids elsewhere in the territory to complete their high school education.

(‘There is always something wrong with this building,’ says Linda Manuel. Photo: Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs/APTN)

It’s not just the physical limitations of the school that hindering student success.,

According to Manuel, kids drop out before they can even read or complete basic math.

“They only come till maybe Grade six or Grade nine and then they quit and say, ‘there’s no point in me going because there is no support,’” she said.

“We don’t have special needs and a lot of them come from social problems in the community.”

Out of six staff, Manuel is the only instructor from the north, let alone the Sahtu.

Sharing her traditions are important.

“With the sewing program I start them at eight years old so they know how to do their own mitts. They just take the patterns. I am trying to give them something that they can hold onto if they quit school they can at least make some money for themselves,” Manuel said.

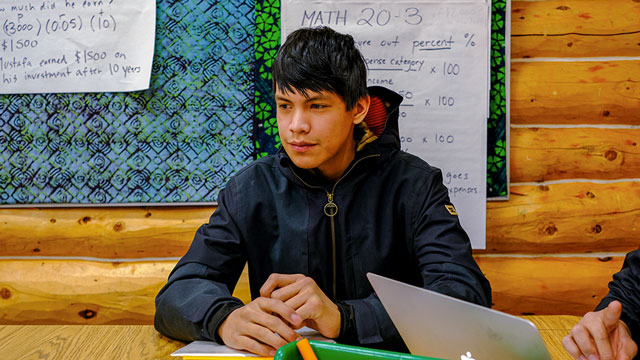

(‘Yeah attendance is an issue’ says grade 11 student Justin Kochon. Photo: Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs/APTN)

Justin Stewart Kochon said he wants to be a heavy duty mechanic once he graduates.

He recognizes how he would benefit from shop and tech classes, if the school offered them.

Kochon, like many students, also didn’t grow up playing many sports. Students have to walk down the road for physical education to use a tiny, rundown gym, attached to the community health centre.

“Yeah attendance is an issue. Most kids will be late by an hour. Work doesn’t start too soon, so they come back half an hour late at least,” Kochon said.

Attendance is dependent on the season, dwindling as family’s go on-the-land or take advantage of the winter road.

Kochon stresses that his peers still are learning beyond the classroom walls, even when they are present at school.

“Every year they always go to their bush camps and stay there a few months. They have been doing it every year so they know a lot,” he said.

Students also need to physically present for classes.

Online courses are not offered because of lagging internet speeds, leaving students high and dry for some pre-requisite courses needed for post-secondary.

(Principal Wayne Dawe uses the makeshift hallway as his office in the school where file folders serve as dividers. Photo: Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs/APTN)

According to Wayne Dawe, the principal, things may get worse before they get better.

As the population drops so too does the money the school receives to operate.

“This past year (2019) we have had approximately 10 students transfer out to different schools in other parts of the territories, Norman Wells, Fort Smith, places like that,” Dawe said.

He anticipates losing one teacher next year.

“I think one of the problems that we have like in Colville Lake is that we are based on formula funding which is based on enrollment which is probably not right for our small schools,” he said.

“Our schools like this need to be need to exist schools with basic programming.”

It’s not just Colville Lake faced with education challenges.

Many remote communities across the Northwest Territories (NWT), schools are struggling to meet curriculum standards.

The NWT department of Education Culture and Employment relies on Alberta Diploma Examinations, Alberta Achievement Tests, and Functional Grade Levels as NWT systemic assessments of educational requirements.

The disparity in scores between large and small community has been longstanding in the Alberta achievement test results.

In the 2016-2017 school year, in small communities only eight per cent of students enrolled in Grade 9 were achieving acceptable standards in math.

This pales in comparison to regional centers, where 41.2 per cent scored an acceptable level.

On Feb 6, the Auditor General of Canada will present a report on Early Childhood to Grade 12 Education in the Northwest Territories.

Historically the findings from the Auditor General have shown students performing the same or worse on tests and low graduation rates.

Dawe noted there are high turnover rates and teacher burnouts in the north.

He said more effort could be made to support and keep teachers in northern communities. Some of the teachers already have had to switch houses multiple times because of frozen pipes this school-year.

“You need to have good quality housing. Teachers have to feel safe when they go home in the evenings, with a nice roof over their heads. Other than that it is the pupil teacher ratio in the north and it’s the learning levels,” Dawe said.

There are 49 schools in the NWT, 39 are outside of the territory’s major centre Yellowknife.

The budget for education is $160 million.

The community along with the Department of Education, Culture, and Employment are currently discussing what the new school will look like and the state of education in NWT in general.

APTN reached out to Renee Closs, superintendent of the Sahtu Education Council. She said she would provide a statement next week.

During campaign season Paulie Chinna, MLA of the Sahtu poised the construction of a new school as a campaign promise, but there is firm no date or location set for when and where a new school will go.

For Linda Manuel, while she pleas for her own classroom to teach her language, she will continue to use her 45 minutes a-day to share with them something they can take outside of the classroom walls.

Correction: The NWT budget for education is $160 million – not $3.1 as written in the original article.

I was born & lived in Yellowknife until grade 2, the school was modern & huge there must be more options to keep the kids in smaller schools to help them flourish.

IDK? BRAD BLANDIONE