If you travel to Rankin Inlet you will see three-layered parkas, traditional qilliqs on coffee tables, and stop signs in Inuktitut.

But Nunavummuit have experienced drastic cultural change in the 21st century.

Prefabricated houses, western education, wireless internet, ATVs, speedboats and store bought food.

You’ll also see lineups for each of the three Tim Horton’s Quick Stops, Chevy trucks with lift kits, and teenagers out with friends snapping selfies for their Snapchat stories.

How does the traditional and modern ways of life coexist for Inuit youth?

You will get different answers depending on whom you ask.

“You feel like you become one of those dolls on a string,” says Terri Kusugak.

(“Being interested in traditions is cool again. I don’t how that happened,” says Terri Kusugak. Photo courtesy: Jessica Davey-Quantick/UpHere Magazine)

Kusugak is 24 years old and from the small hamlet of Rankin Inlet.

She attended Nunavut Sinavisulaq, a one-year transitional post-secondary program for Inuit in Ottawa.

She now works as a performing artist working with Qaggiavuut Society, an up-and-coming creative arts centre located in Iqaluit but spends a lot of time at home in Rankin Inlet.

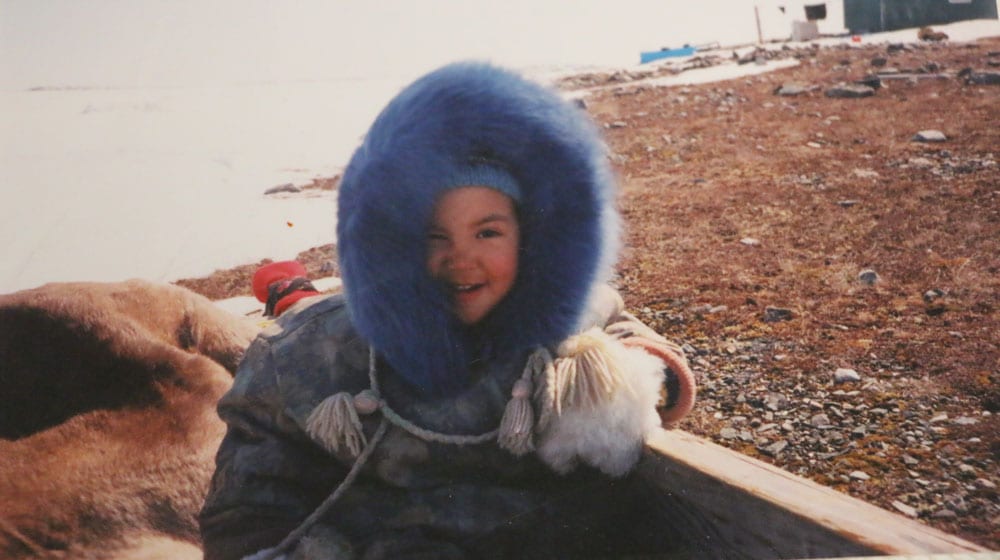

(Kusugak as a child in Rankin Inlet. Photo: Terri Kusugak)

Kusugak says Inuit experience is different with each generation.

“I think in my parents day and age, something was either Inuk or not Inuk,” she says. “Even if you were Inuk, but the way you spoke and the way you acted and everything else was white, then they were white. So things were very black and white, to use the phrase.

“But now, Inuit is just a spectrum. You know, I exist on the Inuk spectrum but I wouldn’t say that I’m more Inuk than my sisters. My sisters, I would think are more Inuk then me even though we have the same parents, because they speak Inuktitut, they’re more interested in traditional things, they have more knowledge on those things.”

But sometimes it can be challenging to reconcile the transition and dual presence of modern and traditional culture.

Youth who use English do so out of practicality, not because they are turning their backs on tradition.

This crossroad has made Mumilaaq Qaqqaq the center of attention when it comes to identity.

“I do everything I can, if I have someone who speaks Inuktitut fluently, I do everything to not be part of that conversation, cause as soon as somebody realizes I don’t speak Inuktitut it is like ‘why do you have those tattoos, who are you to have them,’” she says.

(Mumilaaq Qaqqaq grew up in the isolated community of Baker Lake but went to school in Ottawa. Photo: Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs/APTN)

Qaqqaq attended classes at Fleming College and Algonquin College in Ottawa, Ont.

“When I lived in Ottawa, at least once a day, someone would walk up to me and say what kind of Aboriginal are you,” says Kusugak. “Just every day, at the store, ‘you’re a funny colour, let’s figure this out.’ And at first I was kind of annoyed, like ‘how dare you, I don’t even know you.’

“But after a while I realized they’re curious and they just don’t know any other way to ask—they’re that uneducated.”

Now she works as a wellness program specialist with the Quality of Life Secretariat in Iqaluit supporting frontline workers across the territory who work in suicide prevention.

“I know and can feel that things that I try to say in English, if I knew Inuktitut fluently I could express myself much better,” says Qaqqaq. “When I hear somebody talk in Inuktitut, because certain dialects I can understand, I think, ‘wow that is more powerful than anything someone could say in English.’

See more on our series here: Nunavut at 20

Many youth who use English do so out of practicality, not because they are turning their backs on Inuktituk. This shift can place youth as targets of lateral violence.

“The point of me having these tattoos is realizing that these two sides need to come together, to move forward for me to effectively help, for me to feel like I can own an identity,” she says.

“To feel like it isn’t one side or the other.”

Young people APTN News interviewed say older generations of Inuit don’t always share their story on colonization and trauma.

And younger Inuit are left in the dark.

This has an impact on youth identity.

“Things they tell you later on, stories that you hear, and then you hear again as an adult and you find out which stories are darker than you imagined because your parents were protecting you,” says Kusugak. “I have the benefit of having parents who are able to talk to me about these things. But there are other families where talking isn’t within their value system—not that they’re better or worse, but just that they don’t talk about bad things, or things before a certain time.

“There are people that by talking about it, you’re dredging it, and by keeping silent you’re leaving it to peace. So there are certainly different ranges of education among Inuit my age, depending on the abilities, the mental capabilities of your parents.”

(Seal skins dry on the line in Pangnirtung, Nunavut. Photo: Charlotte Morritt-Jacobs/APTN)

Straddling the gap between old and new world.

Youth are looking up to role models like Dr. Donna Kimmaliardjuk, the first Inuk heart surgeon.

“But when she had gone through that course, all of us were the first to say she’s an Inuk doing her thing, amazing,” says Kusugak. “So now that the pride coin has flipped on its head, being Inuk is not this rare tag that you get with the E number on it.

“Being Inuk is now this identifier where you can be proud behind it.”

By singing Kusugak retains and transforms her Inuk identity.

Growing up only knowing Nunavut as its own territory, she is proud.

“Being interested in traditions is cool again. I don’t how that happened, I think just time and trends, so in my sister’s age, not to say me and my classmates weren’t Inuk or weren’t proud of being Inuk, we just didn’t enjoy being Inuk,” SAYS Kusugak. “In school, we really didn’t talk Inuktitut to one another, we didn’t really engage in Inuk activities like learning songs. We were usually more interested in books or TV, internet. But now, I think that the time for Inuit culture being cool is here again.

“We have Inuit, who are successful at showing their pride in their identity in being Inuk, people like Susan Aglukark or the Jerry Cans.”