Every day, people who suffer from mental health conditions are interacting with the criminal justice system. Most of the time their issues don’t exempt them from prosecution, but sometimes they do.

“People who commit criminal acts under the influence of mental illnesses should not be held criminally responsible for their acts or omissions in the same way that sane responsible people are,” says a Justice Canada report. “No person should be convicted of a crime if he or she was legally insane at the time of the offence.

“These accused can be found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder (NCRMD), more commonly called NCR, or they can be found unfit to stand trial.”

According to Canada’s Criminal Code, a mental disorder is defined as a “disease of the mind.”

Historical context, legislation and background

The not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder (NCRMD) provision in Canada came about by amendments to the Criminal Code in 1992 by former prime minister Brian Mulroney.

These changes were part of broader reforms for mentally disordered offenders.

According to the Ontario Review Board, which has jurisdiction over people in that province who are found by the court to be unfit to stand trial or not criminally responsible, before the changes in 1992 “provincial and territorial courts had no discretion but to automatically detain, in strict custody, persons found not guilty by reason of insanity or unfit to stand trial on what was known as a lieutenant governor’s warrant.”

Each province and territory has its own review board or tribunal.

The 1992 changes eliminated the reference to “not guilty by reason of insanity” and replaced it with “not criminally responsible.” The automatic “strict custody” and the role of the lieutenant governor were eliminated.

Instead, the court is now able to hold a hearing immediately following a verdict and make a decision on the accused, according to the review board’s website. The review board would hold an annual evaluation of the convicted persons’ mental health.

On Feb. 8, 2013, former prime minister Stephen Harper announced the introduction of the Not Criminally Responsible Reform Act (NCRMD).

Bill C-14’s amendments modernized some of the language that had been used in the Criminal Code for more than 100 years. For example, the term ‘natural imbecility’ was removed.

Under the law, people who are found not criminally responsible are neither convicted nor acquitted.

It also gave review boards the power to “extend the review period to up to three years for those designated high-risk, instead of annually. The high-risk NCR designation would not affect access to treatment by the accused.”

According to the legislation, it would also “enhance” the involvement of the victims by ensuring they are notified, upon request, when the accused is discharged; allowing non-communications orders between the accused and the victim; and, ensuring that the safety of victims be considered when decisions are being made about an accused person.

The government at the time said the legislation was part of the federal government’s plan for safe streets and communities.

How it works

“In order to be found not guilty under the NCRMD defence an accused must: have a mental illness, not have the capacity to appreciate their actions, not know right from wrong and not be in control of their behaviour because of their mental illness,” Lisa Kerr, an associate law professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., told APTN.

“This provision, rooted in the Canadian legal system, allows for a verdict that recognizes the defendant did commit an act or omission that constitutes an offence but was unable to appreciate the nature and quality of the act or to know that it was wrong due to a mental disorder.”

On its website, the federal government goes further: “That a high-risk NCR accused person would not be allowed to go into the community unescorted, and escorted passes would only be allowed in narrow circumstances and subject to sufficient conditions to protect public safety.”

Most recently, NCRMD has become the defence of Jeremy Skibicki, the self-admitted killer of four Indigenous women in Winnipeg in 2022. His defence team is asking the court to find him NCRMD.

Skibicki, 37, has confessed to killing Morgan Harris, 39, Marcedes Myran, 26, Rebecca Contois, 24 and an unidentified woman known as Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe or Buffalo Woman, who is believed to have been in her mid-20s.

But the Crown alleges he was not mentally ill at the time of the “racially motivated”, first-degree murders of vulnerable Indigenous women he picked up at city homeless shelters.

“I’m shocked that this defence is being considered here,” Cat Baron, program coordinator and professor of Community and Justice Services at Algonquin College in Ottawa told APTN.

“There is quite a bit of evidence, including his own statements, that seem to suggest that he was pretty clear and intentional about his actions towards the Indigenous women he killed, before, during and after,” she said. “I get that he has a skewed understanding of ethnicity and ethics, but I don’t understand where the call for an NCR assessment came from.”

The Crown must prove that Skibicki had the intent to harm and the mental capacity to commit the crimes and convict him on four counts of murder.

Read more:

Surprise plea: Jeremy Skibicki admits to killing 4 Indigenous women

A case that stood out

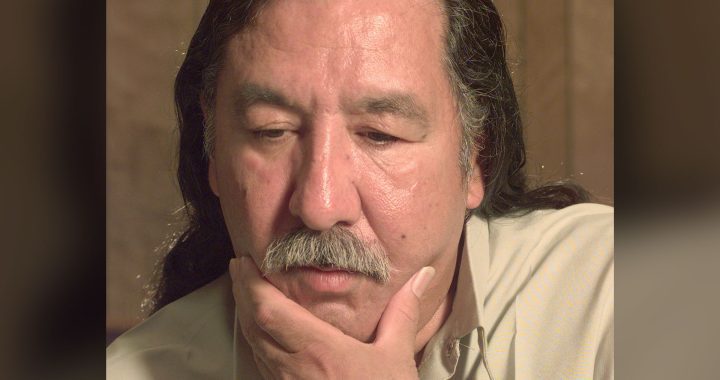

A case that drew a lot of public and media scrutiny of NCRMD was in 2008 and involved a man who used to be called Vincent Li.

Li beheaded and cannibalized Tim Mclean, a 22-year-old Métis man on a Greyhound bus bound for Winnipeg. The murder led to widespread public and legal debate about how the justice system handles cases involving mental illness.

Li, who has since changed his name to Will Baker, pleaded not criminally responsible due to a mental disorder in July 2008.

According to doctors, Li was suffering from untreated schizophrenia at the time. In 2009 he was found NCRMD. He was automatically transferred to the care of the Manitoba Criminal Review Board which placed him in a mental health facility for treatment.

McLean’s mother, Carole De Delley, told APTN her son’s murder became secondary to Li’s condition.

“The system focuses on the killer and how to best meet their needs. With NCR cases, the review board must make a decision that is the least onerous on the patient,” she said.

“That’s messed up. NCR also means no criminal record.”

She note that once a killer is fully released back into society he or she is no longer being monitored.

“That means the crazed-killer-turned-patient could potentially be working with children, the elderly and vulnerable, because they have no criminal record,” she said. “Vince Li changed his name to Will Baker and may well have changed it again.

“We have no idea where he is, he is not required to report anywhere or to treat his lifelong illness.”

Li, now Baker, was released in May of 2015. He served a total of six years.

It comes with a very high threshold

“NCRMD is based on the idea we cannot hold people criminally responsible if they are lacking mental capacity,” said Prof. Kerr. “There is, in criminal law, a bare minimum of capacity someone needs to have before we can say, ‘You are responsible and the state can now punish you.’”

Citing Sec. 16 of the Criminal Code, Kerr said, “It is a very difficult burden to satisfy. It comes with a high threshold. A person has to be incapable of appreciating the act or omission.

“That’s a very serious level of disorder.”

Kerr says, in simple terms, this is someone who has lost their grip on the reality that their actions may cause harm.

“Some people may be suffering from delusions, for instance, if someone thinks killing people will save the rest of humanity. In these cases, the people have lost their grip on basic facts, like if killing a person is wrong because of the nature of the delusion they’re suffering from,” she said. “It’s a high bar to satisfy. It’s also important to note that being found NCR, for many offenders – especially in more serious cases – means indefinite detention.

“After one is found NCRMD, there is a disposition hearing where public safety is considered. If the accused is a significant threat to public safety, the court will order detention in a psychiatric hospital and there will be no end date.

“There are reviews that someone is entitled to in that system and it’s true there are some who are released. Some are successfully treated and that risk to public safety is alleviated. There are also many people who are never released from an NCR.”

But, it leaves families of the victims dissatisfied.

“Vince Li committed one of the most horrific murders in Canadian history and has faded back into society. My son is still dead,” De Delley told APTN.

Five cases utilizing NCR

- R. v. Schoenborn: In 2010, Allan Schoenborn was found NCRMD for the deaths of his three children in British Columbia. In 2008 Schoenborn stabbed and smothered his children, Kaitlynne, 10, Max, 8, and Cordon,5, inside their trailer in Merritt, B.C. An earlier trial found he was experiencing psychosis at the time and believed he was saving his children from sexual and physical abuse. He was found NCR. At his most recent B.C. Review Board hearing in 2022, Schoenborn was granted unescorted overnight visits outside the hospital up to 28 days long, terms that were renewed in 2023 after he declined to have an annual review hearing.

- R. v. Li: As previously mentioned, Vincent Li was found NCRMD in the 2008 Greyhound bus incident. His case became a focal point in discussions about the balance between compassion for individuals with severe mental illnesses and the protection of public safety.

- R. v. Race: Glen Race pleaded guilty to the first-degree murder of Trevor Brewster and second-degree murder of Paul Michael Knott. Race suffered from schizophrenia and was not taking his medicine in May 2007 when he lured men to their deaths. Race believed he was a vampire slayer and a god-like entity at the time of the killings. He was found not criminally responsible, based on a joint recommendation from the Crown and the defence.

- R. v. Kachkar: In 2013, Richard Kachkar was found NCRMD for the death of a Toronto Police sergeant after stealing a snowplow and striking the officer. The case highlighted the unpredictable nature of mental illness and its impact on criminal responsibility.

- R. v. Denny: Denny is a Mi’kmaw who the courts found NCR for an assault on a woman. He was sent to a hospital in Nova Scotia. When he was on a pass from the psychiatric hospital, he got into a confrontation with Raymond Taavel and killed him. He said he was drunk and high on crystal meth. He was charged with manslaughter and given an 8 year sentence.

Not criminally responsible isn’t always accepted

When his parents separated, Kristian Warsing was six-years-old. His mother left him with his dad and step-mother. His father was rarely home and his home life was chaotic.

More than a decade later, according to a study examining his case, the 19-year-old Warsing strangled his step-brother and sister, then proceeded to harass, restrain and beat his step-mother in their Cranbrook, B.C. home.

According to the study, Warsing made “declarations” that would later be used against him in court including, “It’s amazing how much damage an ice-pick can do,” and “It’ll be over in a few hours.”

Warsing was found guilty in British Columbia Supreme Court on two counts of second-degree murder for killing his step-siblings and the attempted murder of his step-mother. His defence was based on being not guilty by reason of mental disorder.

The court determined that Warsing, although suffering from a mental disorder and incapacitated by a bipolar disorder with delusional thought patterns or psychosis at the time of the 1994 incidents, was capable of appreciating what he was doing.

The ruling concluded that the conditions for applying s. 231(5)(e) of the Criminal Code, related to death during the commission of a crime, were not met.