When the RCMP announced in 2014 that they had compiled a list of 1,181 missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada, it marked the first time such a comprehensive police report dedicated to the tragedy had ever been completed.

Almost 5 years later, the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls has only continued to climb but there are no plans for another study.

“I think this country is not fully acknowledging what is going on to do with Indigenous women and girls,” said Sheila North, an advocate and a former grand chief of a Manitoba political organization.

“There should be a way to keep track of what’s going on because the longer that we deny the truth, the longer it’s going to take to fix what’s going on.”

Despite this, it’s unlikely that another major statistical report dealing with the tragedy will be conducted, let alone an active database to track every case.

RCMP report a ‘special project’

Initiated in 2013 by the RCMP, the national police service worked in conjunction with 300 policing agencies and Statistics Canada to create the report, ‘‘Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview.’

The report revealed 1,017 homicide victims and 164 missing Indigenous women and girls spanning from 1980 to 2012.

It also showed that Indigenous women and girls were more prone to violent deaths compared to non-Indigenous women, and similar to other female homicides, most victims knew their perpetrators and most homicides were committed by men.

Read: 1,186 murdered and missing women over past 30 years: RCMP

(Janice Armstrong, the RCMP’s deputy commissioner for contract and Aboriginal policing announcing the RCMP-led report in May 2014)

It was seen as a ground breaking report and garnered national attention.

However, in an email statement Cpl. Caroline Duval with the RCMP National Communications Services wrote, “The 2014 Overview was a special project” and that “The RCMP is not mandated nor funded to conduct statistical research of this kind” and stated further data on homicides of Indigenous women to consult Statistics Canada.

(Lorilee Francis is just one case from the RCMP’s Canada’s Missing site. Francis was 23 years old when she went missing from Grand Prairie, Alta., in October 2007. Photo: Canadasmissing.ca)

As for Statistics Canada there are no immediate plans to undertake another study with the RCMP or any other enforcement agency, according to communications officer Fabrice Mosseray.

Definitive number difficult to determine

Betty Rourke, a family member who lost both her daughter and sister to murder, thinks the RCMP and other policing agencies should invest in another major report.

(Betty Rourke in her Selkirk, Manitoba home. Rourke said her daughter Jennifer McPherson was the sweetest thing and would never say anything bad about anybody. Photo: Martha Troian/APTN)

“They’re the ones that get the case, they’re the ones that are called immediately. If they have funds for anything else, why can’t they have funds for this?” said Rourke.

“We need to remember these women and girls, we can’t forget them.”

Rourke also feels it’s important to know the precise number of cases.

Francyn Joe, president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada believes the number of cases was always higher than the RCMP count.

In an email statement Joe wrote, “They say a lot of crime goes unreported, Indigenous identity may be unknown and historically cases weren’t always taken seriously by police.”

Though the organization once researched and maintained a database of cases in its Sister in Spirit initiative, Joe confirmed that’s no longer the case.

An inquiry, yet no one keeping track

The national inquiry into missing and murdered women and girls cannot provide a clear number either.

“It’s difficult to come to a definitive number of MMIWG in Canada, as police services across the country have different methods of identifying who’s Indigenous, or who is murdered and missing,” said communications lead Catherine Kloczkowski.

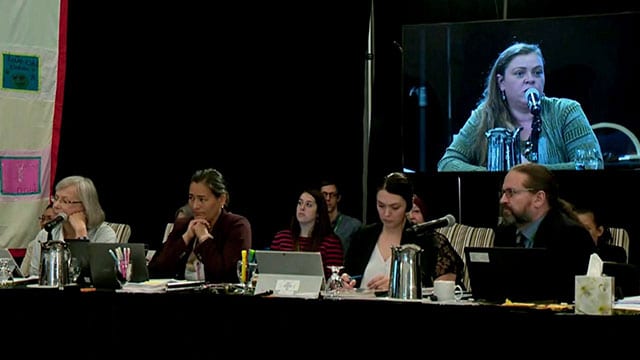

(Commissioners at the institutional hearings on police policies and practices in June 2018 in Regina, Saskatchewan)

After years of not being on former Conservative leader Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s radar, in December 2015 the Liberal government finally launched a national inquiry.

Led by four commissioners, the inquiry has gathered more than 2,300 statements from family members and survivors of violence since March 2017.

(The AFN asserts we need better data collection and analysis when it comes to violence against Indigenous women and girls)

The Assembly of First Nations are also not maintaining a national database.

In an email statement National Chief Perry Bellegarde with the Assembly of First Nations wrote, “Law enforcement agencies across the country must develop coordinated and reliable methods of data collection respectful of women, girls, LGBTQ2S and all First Nations.”

Outside the RCMP numbers, many advocates have suggested the number can be as high as 3,000 to 4,000 cases.

MMIWG Inquiry report due next month

In April, the inquiry will be releasing its long-awaited final report.

In November 2017, the inquiry released its interim report citing a national police task force to be able to reopen cases especially for family members who might feel dissatisfied with the level of investigation into their loved one’s case.

Sagkeeng First Nation in Manitoba is just one community grappling not only from multiple cases, APTN confirmed 20 cases in total, but with many family members who have expressed police failure.

Read: First Nation counts nearly two dozen missing and murdered women

(Danielle Twoheart, 26, died after falling from a three-story balcony in the Caribbean in February 2019. Photo courtesy: Holly Twoheart)

The latest case from Sagkeeng is that of Danielle Twoheart, a young Indigenous mother of two who died after falling from a balcony at an all-inclusive Dominican Republic resort.

Based on a police report shared with the family, it was mentioned that Twoheart’s death was an accident, something the family disagrees with.

Read: Grieving mother believes daughter’s death at Caribbean resort suspicious.

“I hope that there is some glaring, obvious recommendations on how we can move forward,” said Sheila North about the inquiry’s upcoming final report.

“What I would like to see come out of the report is that we, as a nation, find a way so that Indigenous women and girls are safe, and that they’re independent and self-sustaining.”

news.ca