Part 2 of APTN Investigates: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Men – Watch here

Phyllis Fleury carefully puts together safe supply kits, sandwiches and warm clothing before loading up her ’06 Pontiac Pursuit.

Searching in back alleys, behind convenience stores and abandoned constructions sites, she spends her weekends handing out the packages to those in need.

“Hey, do you want a sandwich?” she asks from her car.

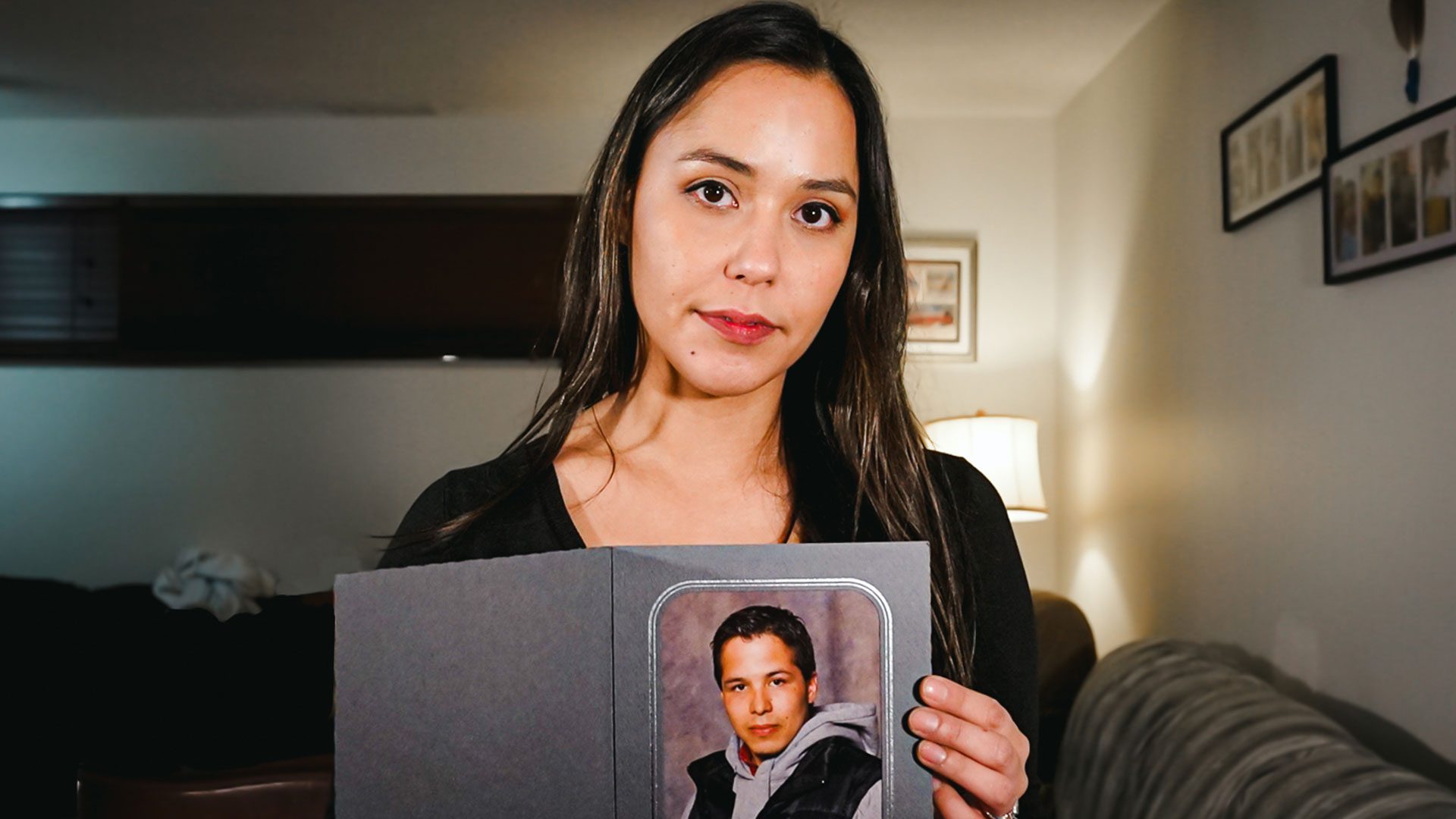

She offers a cigarette and a sticker with information about her missing son to the young woman sitting on the snowy sidewalk.

“This is my son, he’s missing from here, but we’re from Moricetown,” she says. It’s also known as Witset First Nation, a Wet’suwet’en community in Northern British Columbia.

Colten Fleury was just 16 years old when he vanished from a Prince George motel in 2018.

An APTN investigation found that Fleury is one of 19 Indigenous males that have vanished or been murdered along Hwy 16.

A staggering number, each with its own story.

The 725 km stretch of road is also known as the Highway of Tears, beginning in Prince George and ending in Prince Rupert.

It has plagued dozens of Indigenous families for decades and claimed the lives of many.

But lesser known are the Indigenous men and boys of the highway.

“If you were raised with somebody from residential school, you didn’t get the hugs, you didn’t get the I love you,” she said.

Phyllis Fleury’s mother is a residential school survivor.

At the age of nine, Fleury was apprehended by the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD).

Years later, she returned to her grandparent’s care for a short period before being placed back into the department’s care.

The experience left her heartbroken, and she spent years overcoming addiction and intimate partner violence.

“That was the beginning of one of my journeys,” she said. “Part of going to a treatment center is getting rid of the toxic relationships.”

But the cycle of child apprehension continued with her own children.

“This March, I will be eight years sober,” she said.

She credits her sobriety to her son, she was determined to get him back.

And on May 3, 2018, an MCFD worker brought him back to her.

“He came back with just a little garbage bag of clothing,” she said. “He came into my room, and I gave him a hug.”

But the next morning, Colten vanished.

“I worked here, and I cleaned all these rooms,” she said, pointing to the downtown motel they once called home.

Fleury reviewed the motel surveillance footage with the RCMP. She says it showed her son walking away from the motel at seven o’clock in the morning without any of his belongings.

“I wish I could turn back time and say, ‘Hey, where are you going?’” she said. “I just thought he went to the bathroom, but this is the last time I seen him.”

She remembers her youngest as a sweet and funny boy, but she acknowledges that his life was hard.

“It’s missing from missing to missing,” she said. “Mona Wilson was Colten’s auntie.”

When Colten was a baby, they ran into Wilson in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

“We saw Mona across the street, but [Colten’s dad] didn’t want us to see her the way she was. And a month later… she was found in the Pickton farm.”

Wilson was reported missing in November 2001, and her remains were found on Robert Pickton’s farm in February 2002.

The Canadian serial killer was charged with 27 murders, and in 2007, he was convicted of killing six women, including Colten’s auntie.

“I think that might be why there was so much attention on the missing women was because of that Pickton farm,” she said, adding that she wants to see a community liaison for missing and murdered Indigenous men and boys.

Charity Rivard pulls out two old photos albums and envelopes containing dozens of pictures of her former life.

She turns over the pages with a smile on her face.

“He was very traditional, he was super kind, and he was a great father,” she said.

The two were high school sweethearts.

“I met him through my cousin,” said Rivard. “She was actually dating his brother, and she brought me on a family trip.”

Barry Seymour and her spent a lot of time outdoors, often going on hunting and camping trips and learning the traditional ways of their families.

In 2003, they welcomed their first child.

But when he disappeared, it left a hole in the family.

Seymour was last seen at a Prince George trailer park on May 26, 2012.

“Every day, I used to call up north and talk to him, and when I went to call him, my auntie said that he was lost,” said Seymour’s son, Tyrrehz.

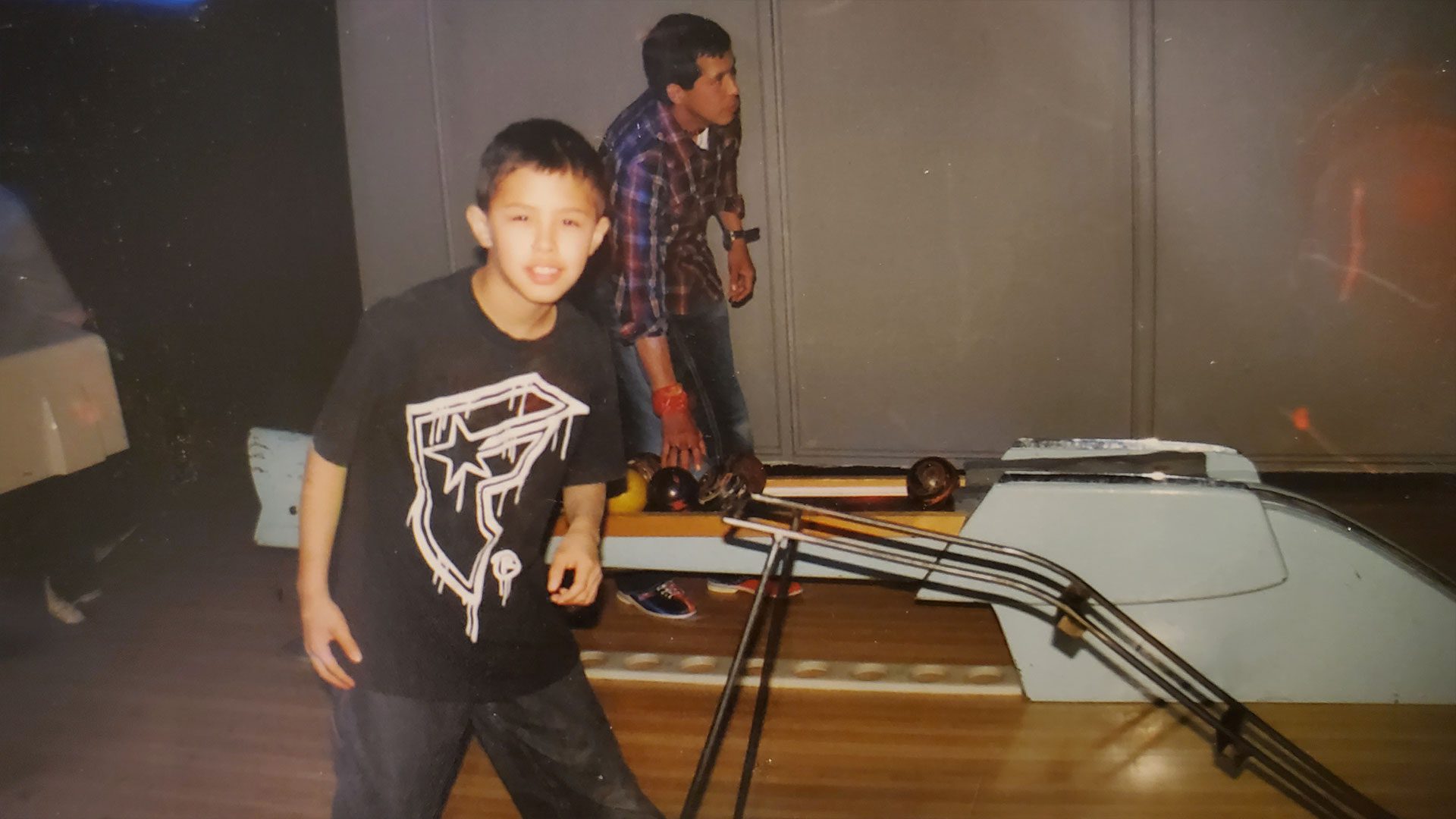

Seymour said his dad used to take him out to the woods and taught him how to live off the land, a memory he now holds close.

“Me, my mom and grandma went to the bowling alley, and that’s where we met up with him, and he brought me presents, and we had a good time bowling,” said Seymour.

He had just celebrated his ninth birthday when he learned the news of his father’s disappearance.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” he said.

Seymour’s young son said it became increasingly difficult to focus on school in the months and years following his disappearance.

“I would see someone that maybe looked like him, and I would just completely flip.”

The pain of his father’s disappearance still comes in waves, but the heartbroken teen is now looking forward to university.

Though he says there are still many unanswered questions.

“I’d just like to see the police actually do something about it,” he said.

Rivard says they haven’t received new information on his disappearance in years.

A national inquiry to investigate the disappearances and murders of Indigenous men and boys is something Rivard says is desperately needed.

“They’ve been dealing with unresolved trauma for so long, especially with the residential school stuff and all that,” she said, adding that intergenerational trauma is still impacting Indigenous communities.

In 2007, 14-year-old Lucas Degerness went missing from Prince George.

Flicking through old photos on his phone, Fred Parry treasures the few remaining pictures of his nephew.

He holds up a photo of young Lucas, smiling at the camera.

“He was adorable, he made me laugh, and he was a good kid,” said Degerness’ aunt, Lorena Parry.

The two used to spend weekends watching scary movies and eating popcorn.

She says his absence has been devastating, and the family wants answers.

“I try not to think about it because this is what happens,” Parry said, wiping away tears.

On June 7, Degerness was called into a school meeting to discuss his grades with his mother. He was sent back to class after the meeting ended.

But he was nowhere to be found.

“The morning of, when he went to the school, I woke up, and he was walking by, and I said, I’ll see you later, bud, and he left,” said Parry. “He had the meeting with the principal and was supposed to be going back to class and never did.”

Fred Parry thinks his nephew may have tried to go back to Edmonton.

“What we thought always was that he went back to Edmonton because that’s where he just came from,” he said.

Degerness recently moved from Edmonton with his mother, and the two were staying with family members.

“Moving from the big city to here, I think it was a downer to him. You’re leaving all your friends, coming back trying to start new.”

Parry says the family was immediately concerned when he didn’t come home.

“Me and my dad were driving the roads all the time, every day, putting posters up all over,” said Parry. “I would look at every single person and wonder if it was him, every single person.”

He hopes to see more awareness raised about the growing number of missing and murdered Indigenous men and boys in Canada.

“The first star I see, I make a wish, and it’s always about him coming home.”

Anyone with information on the disappearances of Barry Seymour, Colten Fleury, or Lucas Degerness are asked to contact the Prince George RCMP at 250-561-3300 or Crime Stoppers at 1-800-222-8477 (TIPS)

Editor’s note: The original story said that Lucas went missing in 2011. Lucas has been missing since 2007. We apologize for the error.