Chris Nicholas kneels down in the basement of the Mi’kmaw Native Friendship Centre in Halifax and points at the old boiler that, off and on, keeps the place warm.

It needs to be drained every day, which floods the basement with steaming hot water.

Thing is, Nicholas, from Tobique First Nation, isn’t a maintenance guy.

“I’m an IT guy I’m not a boiler furnace person, but you know we use the resources we have, to stay functioning for our program,” says Nicholas, a member of Tobique First Nation.

Nicholas says the centre is a big part of his life.

“I became heavily involved in the youth program which after that in the youth program and through my Aunt I met my wife,” he tells APTN News. “We ended up having two children and involving them in the Aboriginal head start program.”

He says he does what he can to keep the old building going.

“It’s a major problem that we need a new friendship centre,” he says.

This old centre – a fixture in Halifax since the early 1980s – is falling to pieces and was supposed to be replaced in 2021.

Nicholas says the building is no longer safe.

“That’s only our pipes that are wrapped in asbestos that doesn’t include our walls and our ceilings that are stucco asbestos,” he says.

So they are preparing for a move to a temporary location.

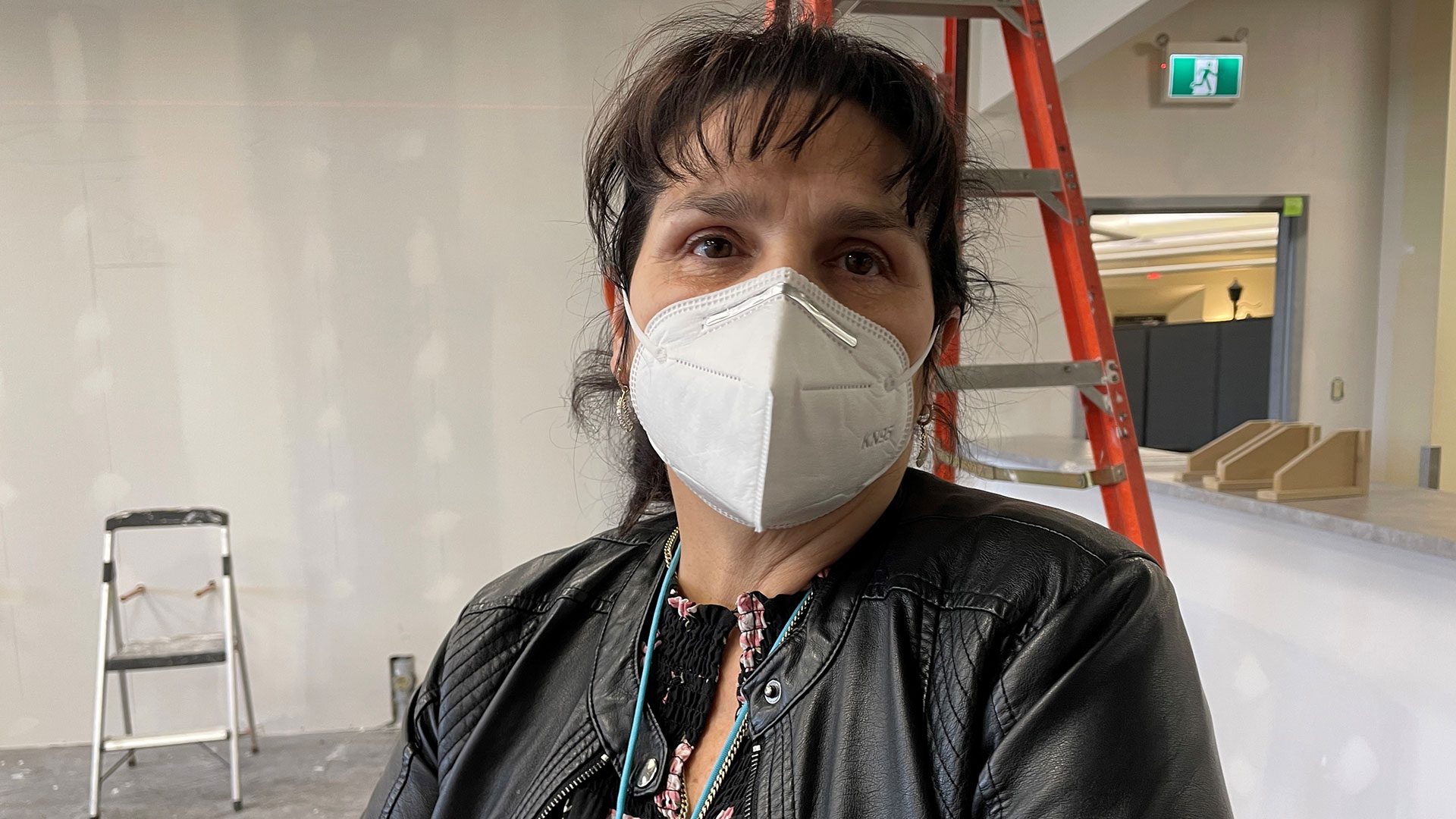

“We have it for the three years and then we will be homeless in three years, that’s what I keep telling myself,” says Pamela Gloade-Desrochers, executive director of the centre. “But it gives us three years to actually figure out what is going to happen with the new building.

“We are working with the federal government as well through ISC (Indigenous Services Canada), on the possible extension because we know even if we started building today, a new building, probably still wouldn’t be ready in three years.”

Because of the pandemic, demand for services increased at the centre.

“If that hadn’t been there, that safety net of a friendship centre in Halifax, we roughly service about seven thousand people a year, if that hadn’t been there, there would have been a lot of people that would have continued to fall through those gaps and would have been left behind,” says Gloade.

The centre offers more than 30 programs and has 5,000 people who use its services.

On the second floor – where gatherings and events are held – Nicholas points out a portion of the ceiling where signs of a leaky roof are clearly evident.

“I mean we’re to the point right now where we literally just stuck white duct tape over it,” he says. “Next rainfall it’s just going to come through again and every time, we’re just sinking more and more money into repairing that.”

Staff at the temporary location are slowing moving in.

Gloade-Desrochers says the government needs to live up to its 2018 promise to provide cash for a new building.

“Everybody talks about truth and reconciliation, and yet when it comes time to do the actual hard work of doing it, I’m not sure people actually want to,” she says. “If you really want to make a difference in our communities, step up and invest, step up and do the hard work.”

In 2018, the friendship centre unveiled plans for a new building, at the location of the old Red Cross Blood Services building.

About 100 people attended the event, Elders and community members, in hopes a new building would open in 2021.

The federal government promised to work with the centre to find money – but COVID-19 hit, and everything was delayed.

Fast forward to 2022, Indigenous services says it’s still looking for cash.

“In addition to funding regular programming and supporting the Friendship Centre’s move to their interim location on Brunswick Street, we are committed to working with the Mi’kmaw Native Friendship Society and other stakeholders to identify potential funding sources for a new Friendship Centre,” says Nicolas Moquin, a spokesperson at Indigenous services,