Gibbet Stevens’ red parka stands out against the snow and overcast sky as she says a few prayers for her ancestors buried in the ancient Mi’kmaw community of Malagawatch.

“I feel their presence,” says Stevens. “That’s how strong this place is for me.”

Stevens’ parents were forced to move to Eskasoni during centralization in the 1940s, when Indian Affairs enacted a policy to relocate Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia.

Approximately 1,000 Mi’kmaq were uprooted. Half of those who moved, eventfully moved back, though often their homes and livelihoods were destroyed.

“We need a public apology,” says Eskasoni Chief Leroy Denny “And that’s what I’m seeking on behalf of my community. I need a public apology and maybe some sort of compensation for the issues we deal with today.”

Eskasoni is the largest Mi’kmaw community.

“Reason it’s the largest because of centralization,” says Denny. “Is it a good thing or a bad thing? We still deal with overcrowded housing, high rates of diabetes, high rates of suicides, poverty – 70 per cent child poverty.

“And we’re battling back, because we know our Elders went through a very dark period of time,” says Denny. “And they remind us they don’t want their next generation to go through what they been through.”

(Gibbet Stevens visits Malagawatch, an ancient Mi’kmaw community in Unama’ki (Cape Breton), and home to her parents before they were relocated during centralization. Photo: Trina Roache/APTN)

The records reveal the department of Indian Affairs wanted to save money, and also move the Mi’kmaq out of sight and away from cities and towns.

Government officials promised houses, jobs, and healthcare to entice the Mi’kmaq to move to two reserves, Eskasoni and Shubenacadie, or Sipenkne’katik.

But the promises of houses and jobs were not borne out in reality.

Stevens says her parents were only allowed one bag each and they were piled into the back of a pickup truck.

“Before they left, they were promised a new house and when they got there to Eskasoni, their house was incomplete,” she says. “You could see through the slats, you could see the outside.”

Mi’kmaw Elders recall Indian Affairs burning people’s homes behind them as they left. And then they moved into shells of houses; some even lived in tents through long harsh winters.

“They were all half frozen,” says Ethel Johnson. “You know, that’s where all the sickness came from, living in tents, because we were the lucky ones, because we had a house.”

Johnson was seven years old when her family was relocated to Eskasoni. She remembers living in an unfinished house with two other families when they first arrived.

“My mother got sick,” says Johnson. “I don’t know if it was from the cold. And she was pregnant. But she developed TB [tuberculosis], so then we had to go to the residential school. It was very sad, the treatment and the promises that were broken,” says Denny. “It’s a dark history that can’t be just put under the rug.

“And we want to tell the government that we need a public apology and have a discussion of some sort on compensation,” she says.

(Mi’kmaw Elder Ethel Johnson was seven years old when her family moved to Eskasoni during centralization.Photo: Trina Roach/APTN)

Denny is picking up a fight that the Union of Nova Scotia Indians started in the early 1970s.

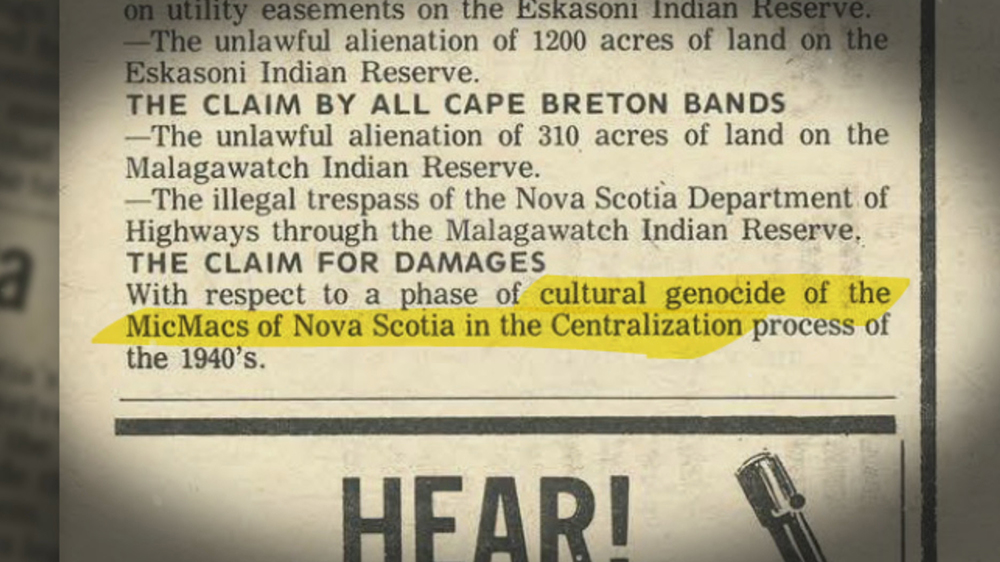

The organization laid out a case for Aboriginal title and land claims in a 1974 article in the Micmac News, with the headline “Who Owns Nova Scotia?”

Under the heading “The Claim For Damages,” the Union referred to the “phase of cultural genocide of the MicMacs of Nova Scotia in the Centralization process of the 1940s.”

Don Julien is the executive director for the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq. In the 1970s, he worked as a researcher for the Union of Nova Scotia Indians.

Centralization was an early focus, but fell off the radar as the push for Mi’kmaw treaty rights and land claims took precedence.

“Maybe we should be resurrect it,” says Julien. “That’s another claim against the federal government. All the people dislodged from their communities.

“You had residential schools. You have Indian Day schools. So maybe that’s next.”

The government of Canada apologized for its role in residential schools in 2008 and currently, thousands of Indigenous people are filing claims under a class action lawsuit for their experiences in federal Indian day schools.

Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall says the colonial systems implemented by Indian Affairs, like residential school and Indian Day schools, are all related.

“To me, centralization, it’s very difficult to talk about it in isolation,” says Marshall. “As we see that as one of the many ways the government has used to eradicate or to kill the Mi’kmaw spirit that’s been in us.”

(Albert Marshall is a well-known Elder in the Mi’kmaw community of Eskasoni. Photo: Trina Roache/APTN)

Marshall was born in Eskasoni before centralization.

“The happiest part of my life would have been was here in Eskasoni prior to residential school,” says Marshall. “Because here, we were we were able to live off the land, to constantly engage and learn from the Elders.

“And then, unfortunately for us, the government initiated this program of forced relocation or centralization. That’s when our culture really took a really good bang.”

Mi’kmaw Elder Ernest Johnson describes the Mi’kmaq as “independent,” “capable hunters and fishermen,” “resilient,” and “survivors,” despite hundreds of years of colonization.

But he says that all changed with centralization.

“Mi’kmaw people began to lose their dignity. They began to lose their pride. Their own way of life was turned around,” he says. “And they began to follow what was designed for them. And eventually to almost total dependency.”

His family was relocated to Eskasoni when he was six years old.

He says in addition to being forced to move, poor housing, and lack of jobs, a damaging aspect was the increased control of the Indian agent.

“You couldn’t go to the store without a piece of paper from the Indian agent saying you could buy these things.

“We were free. And when we came here, it was like going into a cell, your own cell,” says Johnson. “Like the word incarceration, I think that we saw what being incarcerated was about.”

Research in the 1980s by social work professor Fred Wien studied the impacts of centralization and noted the “poor living conditions,” a dramatic rise in welfare rates, and “alcoholic abuse” from the “economic and social breakdown.”

“I honestly and truly believe that psychologically, spiritually, and even cognitively, we have not recovered from that yet,” says Marshall.

(Screen capture from an article that appeared in the Micmac News, October, 1974. Photo courtesy: The Beaton Institute)

Denny wants to start those conversations on what compensation might look like as soon as possible. And he says an apology is an important step toward educating people about little known, but dark chapter of Mi’kmaw history.

Mi’kmaw Elders agree.

“Yes, an apology is essential,” says Marshall. “But there has to be some action behind that apology. And I do hope that next 20, 30, 50 years from now, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”

Gibbet Stevens’ path to reconciliation leads back to Malagawatch.

“I’ve always loved it here. I have a passion for it. I wanted to build my home there,” says Stevens. “Over the years, I’ve talked about it and I dream about it. My ties are there, because my parents came from there.

She stands on the shoreline of the Bras d’Ors Lake, looking at the spot where her mother’s house used to be before it collapsed long ago.

“I just feel like my all my ancestors are here watching over me, including my parents. So, yeah, it means a lot,” says Stevens. “Even just to be here today and to be doing this, I feel honored.”