Kenneth Jackson

Jaydon Flett

APTN National News

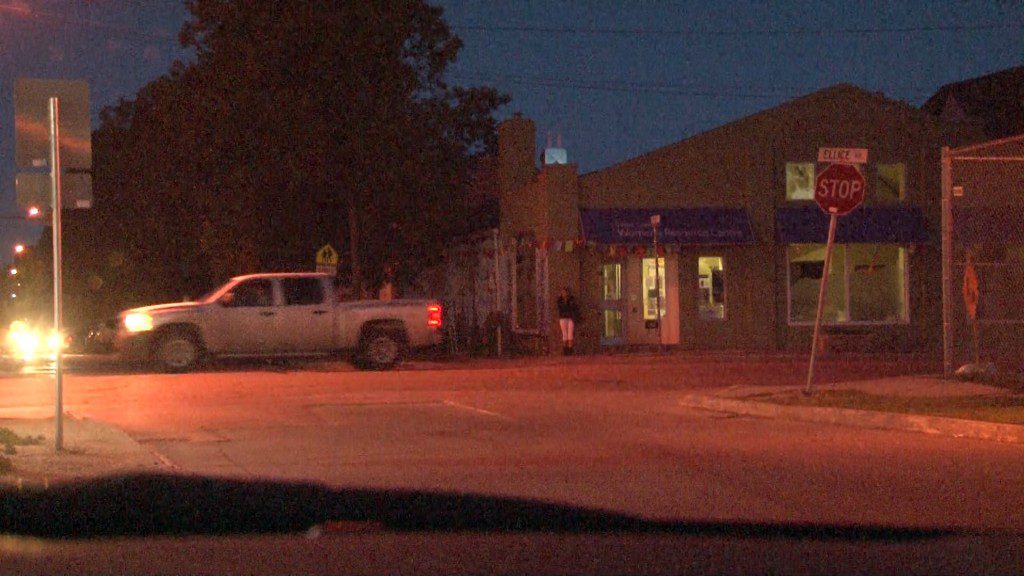

WINNIPEG – Just beyond the glow of the street light, she sits in the shadows writing down license plate numbers of men stopping at the corner in the middle of the night.

They’re trolling for sex on the edge of downtown Winnipeg.

In less than two weeks she’s recorded taxicabs, a city vehicle but mainly guys in nice cars.

They come quick and often. Rolling up to talk to an Indigenous woman, 21, standing on the corner of Ellice Avenue and Furby Street.

They don’t see the girl in the shadows.

A black truck pulls up at just after 6 a.m., the 20th car she’s recorded in June on that corner, for the same girl – her friend, who we are calling Amy.

She gets in and the truck drives away.

If Amy doesn’t return, the girl in the shadows will at least have a plate number to give police.

She records the plates because she doesn’t want her friend to suffer the same fate as Tina Fontaine, who was last seen on this corner last August – when she walked away with a man offering her money for sex. Days later, her 15-year-old body was pulled from Red River wrapped in plastic.

Her murder remains unsolved and Amy knows the dangers of working that corner.

Especially since the corner has been in the news in the last few weeks. Just two buildings north on Furby is an apartment building where Fontaine’s cousin was charged by police this month for pimping a 17-year-old girl from inside Unit 4. Fontaine was also reportedly inside the building before she went missing.

“It’s pretty scary and I stand right there,” Amy told APTN National News. “You always have that scared feeling, but once you start to talk to them, and get down to the deal, you’ll know they’re serious, but then again you just don’t know.”

Learning the “Life” in CFS

APTN hit the streets last week in Winnipeg to talk to girls and women.

As a ward of the province Amy said she learned the life she leads now.

“I think I turned bad when I went into CFS,” said Amy. “When I started hanging out with the girls that were put in CFS I started to get into lifestyles that were above my age. You get involved with them and you become their friends and you become their lifestyles and become involved with what they do.”

APTN was told stories of kids being put in hotels at young ages where they hung out with sex workers.

“We had a lot of prostitutes coming and going and they’d give us free drugs or alcohol just to hang out,” said Faith, a First Nations woman who was once in CFS, but who is not a sex trade worker. “Prostitutes get lonely too. Us kids had bad lives, and so did they, and we really connected with them and they gave (us) our basic needs which was smokes, alcohol and drugs.”

The province said they’ve stopped putting kids in hotels under their care as of June 1 in Winnipeg. The last numbers have about 10,000 kids in CFS, 9,000 of them are First Nation, Metis and Inuit.

Faith, who asked that her real name not be used, said the drug situation was pretty bad. Many of those who started smoking weed moved on to meth and crack.

She said the younger kids would learn from the older kids.

“I remember eight-year-olds high. Why? Because the older kids were doing it. Not many kids sobered up. I knew hundreds of kids and only a couple made it out of CFS sober,” said Faith. “I got kicked out the morning of my (18th) birthday. Some kids got worse. I was lucky I had family to stay with. Some kids went straight to the homeless shelters.”

Sex Workers Along Ellice and Sargent Avenues

It’s just past midnight on night of June 15 and an Indigenous woman is standing on the corner of Ellice and Home Street. Three guys are standing in front of Chicken Delight across the street.

She’s waiting for a John and they’re staring at her. But as they walk away a different man walks up.

He turns down Home Street and waves to her. She quickly follows.

She leads him to a spot she knows well, where she charges $40 for oral sex.

“Follow me,” she says.

They walk behind an apartment building, down an alley between houses to a latched gate. She lifts the wire latch and walks onto a short path that leads to someone’s backyard on Home Street. It’s dark and a privacy fence provides enough cover.

Her name is Kelly, 27, and she entered CFS at the age of 13.

Within a year she was addicted to crack cocaine. The First Nations woman said she began selling herself to men who wanted to sleep with a child.

When she turned 18, CFS kicked her out.

“They just left me alone after that,” she said of her 18th birthday. “They didn’t help me find a place or told me anything about resources. I had to find everything on my own. It was really hard on the streets. I was eating day-by-day. I’d be staying at different places. I’d be staying at crack shacks … have to go out and sell myself.”

She says she has five kids – all in CFS and doesn’t see them often.

When she was young Kelly wanted to be a pediatric nurse but isn’t close to leaving behind the life she learned in CFS.

“Not very close, not very close at all,” she said. “It’s very hard out here, especially with all the gang wars and drug wars.”

Wandering the Streets of Winnipeg

CFS kids can be seen all over downtown Winnipeg. Some are seen stumbling, intoxicated from whatever drug or drink they were able to find. Many like to go hang out behind the Portage Place mall in downtown.

APTN found two 16-year-old girls heading there June 16 at around 9 p.m.

They can’t be identified because they’re both under the care of CFS.

But they wanted to tell their story.

Jennifer, 16, her younger brother and sister were removed from their mom when she was nine far from Winnipeg.

She said CFS brought all three to the city and put them in hotel with connecting rooms at the Best Western downtown.

On the floor were two boxes of food, mostly junk food. Twice a day, case workers assigned to watch them would change shifts.

“We never went anywhere. We stayed in the room,” she said, remembering it was hard on them, particularly her brother, who was two at the time. “They’re crying. We’re crying. They were scared. They knew they didn’t have their mom.”

Despite being in connecting rooms the case workers would only let her see her siblings for a few minutes a day. And they were too young to wander outside the building.

This lasted for a few months before they were put into a foster home.

Six years later, Jennifer is struggling.

“I haven’t been in school since October/September. I’ve been going to the hospital. I’m suicidal… because of CFS,” she said then shows the scars on her arm where she cuts herself.

She said CFS workers are always late to returning calls and doesn’t feel as though they’re much help.

Her friend Julie said she was taken by CFS when she was an infant.

“Every time my mom would come see me I would cry for her to come back. That’s when I started getting into drugs and alcohol,” said Julie, who has been sober since January.

Neither are sex workers but said grown men approach them on the streets. Julie said she was sexually assaulted in March 2014 when she met people on the street.

“To this day … I’m scared to walk around at night. That’s why I stay with friends all the time,” she said. “You don’t know who is around. You don’t know what is going to happen to you.”

Despite it all, she dreams of becoming a nurse and helping homeless people. Jennifer wants to build houses … hopefully for the homeless.

That was also a common theme among the CFS kids. When asked what they wanted to be, they all picked jobs that help people.

CFS kids Look Out for Each Other

Selena Templeman, 43, said that’s because CFS kids feel alone, their only family is the people they meet on the street.

“People look at us being in CFS as ‘oh, they’re just unwanted people,’” said Templeman who was put in CFS at the age of two and isn’t a sex worker.

APTN found Templeman hanging out at a downtown shelter.

“We’re just like castaways. Nobody wants us. So, around here, we kind of blend in together like a community,” she said. “We watch out for each other. … Like an extended family.”

That’s what the girl in the shadows is trying to do for Amy but she wants to remain unseen, even for this story.

“Some stories are meant to stay on the street,” she said.

But Amy wants to tell her story. She told APTN she thinks by doing so it could help other girls who may fall into the “life.”

She said there’s “creepy” guys out there that want “really messed up things” when they pick her up.

For the most part, she feels they’re lonely and almost always white guys in nice cars.

“There’s lawyers, computer guys, doctors, train guys … there’s one guy who said he was a cop but he said he was off-duty,” she said, adding cab drivers stop often. “I don’t like going with them. I always say ‘fuck I hate cabs’ and walk away. They’re cheap. They want lots for less.”

Amy has been sleeping all day and doesn’t have much time to talk. She has to get to the corner. She allowed APTN to film at a distance.

Almost as soon as she walks to the corner a young man, who appears to be white, walks up to her and they chat for a few minutes. He then points to what’s believed is his car and she leaves with him.

The person watching her keeps an eye on her and leaves.

Amy will be home soon after and they’ll do it again.

what a horribly written article. These kids are damaged when they come into CFS care not because of CFS care.

Victims many if not most prostitutes are… how are you supposed to react to adults feeding underage children alcohol and drugs to the point where they call it “basic needs”? These women have become the same system they were victimized by.

At first I thought she was writing down license plate numbers so she could shame them on the Internet. Turns out she’s part of the operation. Shows what I know.

are you thinking thats her pimp? the article does not identify who the girl is in the shadows.