A hallway inside one of Canada's prisons. Photo: APTN File

The first three offenders in Canada to use medical assistance in dying (MAiD) were shackled and watched by prison guards, parole officers and correctional officials alongside family members, APTN News has learned.

They were among nine federal inmates to seek MAiD since it became legalized for people with a terminal illness in 2016, according to the latest figures supplied by the Correctional Service of Canada.

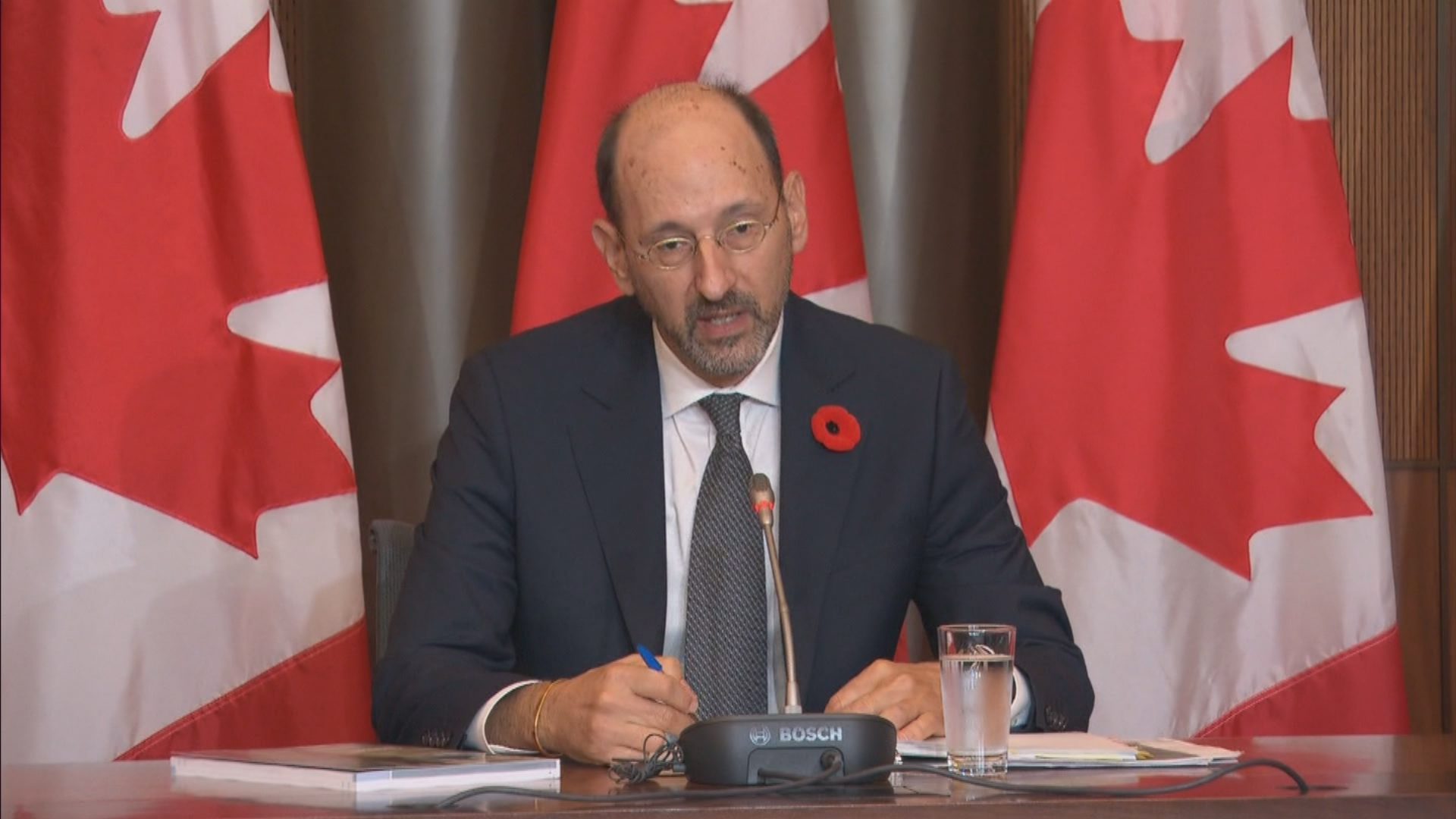

Nine was the total number up to March 31, 2022, but more offenders have sought euthanasia since then, says Ivan Zinger, the Correctional Investigator of Canada.

The first three inmates died inside a prison healthcare unit instead of a hospital or care home.

Something Zinger is strongly opposed to.

“Under no circumstances should the procedure of MAiD be dealt with inside a penitentiary,” he tells APTN. “That is highly problematic, unethical and immoral in my view. I think we would be the only jurisdiction in the world who would do that.”

A spokesperson for corrections declined to provide the names, ages, ethnicities or crimes of the inmates who used MAiD for privacy reasons.

But Judith Gadbois-St-Cyr says its guidelines ensure “a robust and compassionate process for those who may wish to access these services.”

Gadbois-St-Cyr described the corrections’ process as “comprehensive” and one that “contains numerous safeguards to ensure that federally incarcerated individuals are afforded the same rights as all other Canadians with respect to the provision of MAiD.”

The MAiD law legalized assisted death for Canadians 18 and older with terminal illnesses in 2016. It was expanded in 2021 to include those with serious and chronic physical conditions, even if that condition was non-life threatening.

The law was supposed to change again this year to include some Canadians with mental illness. But the government agreed to delay psychiatric MAiD applications for two years after hearing it may be too easy for vulnerable people to die.

APTN has learned some of the first inmates to use MAiD were Indigenous and all of them were male.

Kim Beaudin, vice-chief of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples and a member of corrections’ National Aboriginal Advisory Committee, says he understands why Indigenous inmates – who comprise 32 per cent of the prison population nationally – would consider assisted death.

“I’m not in support of (the law) because I’ve always believed there should be hope for them to get out of there,” Beaudin says.

“But a lot of people have given up; a lot of Indigenous people have given up inside.”

Gadbois-St-Cyr says an offender seeking MAiD meets with a physician or nurse practitioner to discuss their application and undergoes an eligibility assessment. The offender is also offered support services from a chaplain, Elder or mental health professional, she adds.

CSC says there have been no additional MAiD deaths since March 31, 2022, the latest data it has available.

Canada has approximately 13,000 federal inmates, many of whom Zinger says are aging and infirm.

He says offenders suffering from illnesses like dementia, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease have the same rights as ordinary Canadians to apply for MAiD.

But he wants to see corrections do a better job of implementing the process – even when using an outside facility.

Zinger documented the first case of an inmate using MAiD in an outside hospital in one of his annual reports to Parliament.

The inmate was ”escorted by correctional officers” before being “handcuffed to the bed and (the officers were nearby) while the procedure took place in presence of the family.”

In a follow-up letter to the chair of the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, Zinger says this is unacceptable.

Photo: APTN file

He is particularly upset, he wrote in the four-page letter, that corrections is under no obligation to report MAiD deaths to him like it is other deaths of inmates.

“We don’t receive any of it,” he tells APTN, which obtained the letter through access to information and privacy (ATIP). “And that’s part of the problem that I flagged to the chair.”

Jessica Shaw, an associate professor of social work at the University of Calgary, interviewed a different group of inmates about death and dying in prison for research purposes.

“These were all men who were serving indeterminate sentences (without an end date),” she says, noting they wanted to talk about assisted death but weren’t intending a MAiD death themselves.

Shaw noted that in Canada, six out of 10 Indigenous offenders serving life sentences are more than 50 years old.

“That’s much higher than (inmates) who are non-Indigenous, so you’ve got older people spending more time in prison not knowing when they’re going to get out, and this is just increasing every year,” she says.

“Some were thinking about what serving a life sentence when you’re coming to the end of your life means.”

She says some of them were patients in a palliative care program offered in one prison.

“More than one person shared that they felt like part of their duty to own their debt to society was to free up space, essentially. Knowing that they were going to be there forever.”

Shaw says all of them wanted to use MAiD to end their suffering.

And it is agreeing on a definition of suffering, she notes, that is fuelling the public debate about who will qualify for MAiD when the eligibility is expanded to include psychiatric illness.

And could see more applications from inmates.

“The emotional suffering and psychological suffering that prison can cause, is and would be a factor for them wanting to seek MAiD – not that they’re eligible,” she says.

“In Canada, it’s not possible right now…but isn’t that something that we do have people who would rather die than endure the suffering they have to go through?”

Shaw says she was asked to write a report on assisted death in prison for the federal government.

She says she added some questions for law- and policy-makers to ponder as they review the criteria for MAiD:

- What is the function of prison if an offender is physically unable to commit a crime anymore and destined to die there: rehabilitation or punishment?

- Should relief be withheld if, due to aging or illness, an offender is no longer able to understand why they’re incarcerated in the first place?

“My personal (and) professional opinion is I would like to see a lot more decarceration,” she says, “…especially around end of life. I think we have to question more deeply the purpose of keeping someone locked up as they’re near death.”

Editor’s note: The story was updated to correct information that Jessica Shaw interviewed a different group of nine inmates than those who used MAiD.