Lynn Thompson walks down a back alley in Saskatoon – past garbage bins, needles and condoms strewn on the ground – to get to the door of the only place in the city that offers a needle exchange and methadone, a program that hopes to stem the spread of HIV and Hep C.

“This is the back end of the needle exchange. As you can see it’s all against a garbage bin,” she says. “That’s what bothers me in this province. Is that we are considered bottom of the barrel, scum, garbage.”

Thompson was also our guide into some of the lesser known parts of Saskatoon’s inner city.

Places some might call dark, even in daylight.

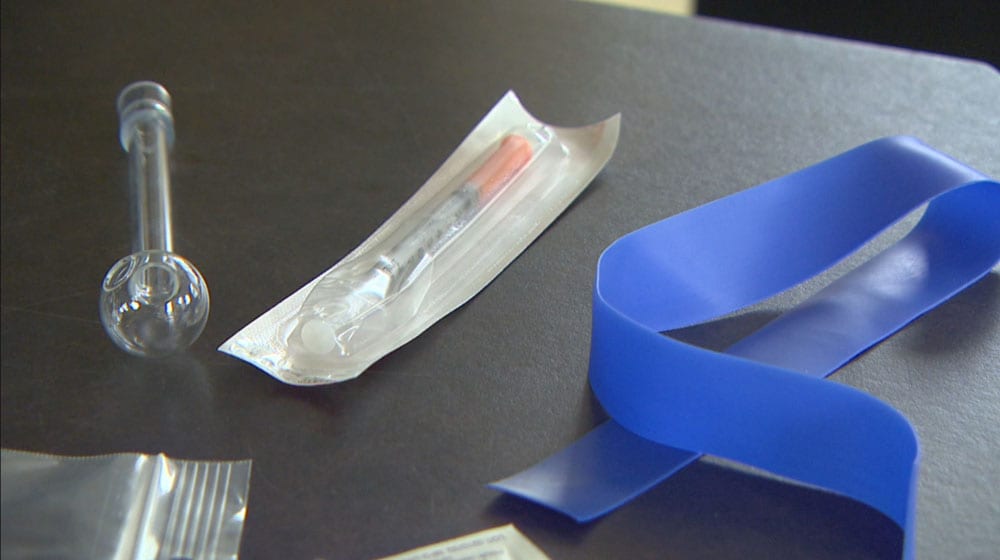

(AIDS Saskatoon displays some of the drug paraphernalia they distribute as a harm reduction effort. Executive Director Jason Mercredi said pipes are effective tools and the province of Saskatchewan jumped on funding a pipe program to both discourage IV use and to reduce pipe sharing. APTN)

HIV and hepatitis C infections are rising at a distressing rate in Saskatchewan and Saskatoon’s inner-city community is one of the hot spots.

People living with HIV and those who provide service in the community say infection still happens through sexual intercourse, but needle sharing for intravenous drug use is now the leading cause of infection.

Harm reduction initiatives, like needle exchanges, pipe exchanges, and free contraceptives may be having an impact, but other initiatives, such as safe injection sites, don’t exist.

Lynn Thompson, a long time Saskatoon resident and HIV fighter for 20 years, says sharing needles is common.

“So often they will use a needle 10 to 20 times and they will share it amongst a group of people,” she says.

Thompson says accessing services is frustrating and would like to see a safe injection site.

Jason Mercredi, the executive director of AIDS Saskatoon, says that it’s understandable how some people are irritated by the lack of services and how existing services aren’t enough, like the needle exchange program.

“That means if I have a needle I can get a needle,” he says. “And [needle exchange programs] don’t actually decrease the HIV rate.”

Indigenous people account for 80 per cent of the new infections in Saskatchewan, and many of them are women.

Women like Lynn Thompson.

“When I contracted HIV 20 years ago that vastly changed my life,” she says.

“I was quite afraid of infecting other people if I got an injury.”

(Lynn Thompson, holds a water container handed out to intravenous drug users. She says it’s a vast improvement over the puddle water users have used in the past for their injections. Photo: John Murray/APTN)

Although men are still infected more often, that rate has dropped and the number of women infected is increasing year over year.

“It was known as a gay man’s disease,” Thompson says. “It’s no longer that, especially in our province of Saskatchewan. It’s actually a young Aboriginal woman’s disease.

“Our young women are contracting it at phenomenal rates.”

Mercredi agrees, saying the use of dirty needles is becoming the most common cause of infections.

“I would say number one, with a bullet, for the last 10 plus years has been injection drug use,” he says.

In those dark places in Saskatoon that Thompson brought us, APTN saw evidence of the sex trade, violence, homeless people living in abandoned structures and a lot of litter from shooting up – a common term for injection drug use.

Although drugs like heroin and cocaine are used, Thompson says meth is cheaper and opiates can often be obtained for free.

“A lot of that is due to prescribed drugs,” she says.

Ernie Louttit, a retired Saskatoon police officer and author says he is ok with accountable needle exchanges, meaning one-to-one exchanges but he has concerns about safe injection sites.

“Safe injection sites, I think, could work,” he says.

“I’m not a big fan of them because all you’re doing is facilitating organized crime.”

(Saskatoon’s Pleasant Hill is a vibrant area often busy with shoppers and pedestrians but the neighbourhood is also struggling with gang violence and illness. APTN)

The “broken window” theory is the notion that run down areas attract crime.

Some people equate that with needle exchanges and safe injection sites.

Mercredi understands that.

“Nobody wants to find a needle in their backyard or their front yard,” he says. “I think a robust needle pickup program is needed. Needle drop boxes through the community are vital.

“But I think we have to make sure that the primary goal is reducing HIV infections.”

Reducing the Transmission of Blood-Borne Viral Infections & Other Injection Related Infections

“Self-reports from users of the INSITE service and from users of SIS services in other countries indicate that needle sharing decreases with increased use of SISs. Mathematical modeling, based on assumptions about baseline rates of needle sharing, the risks of HIV transmission and other variables, generated very wide ranging estimates for the number of HIV cases that might have been prevented. The EAC were not convinced that these assumptions were entirely valid.

SISs do not typically have the capacity to accommodate all, or even most injections that might otherwise take place in public. Several limitations to existing researchwere identified including:

Caution should be exercised in using mathematical modelling for assessing cost benefit/effectiveness of INSITE, given that:

There was limited local data available regarding baseline frequency of injection, frequency of needle sharing and other key variables used in the analysis;

While some longitudinal studies have been conducted, the results have yet to be published and may never be published given the overlapping design of the cohorts;

No studies have compared INSITE with other methods that might be used to increase referrals to toxification and treatment services, such as outreach, enhanced needle exchange service, or drug treatment courts. objective evidence of sustained changes in risk behaviours and a comparison or control group study would be needed to confidently state that INSITE and SISs have a significant impact on needle sharing and other risk behaviours outside of the site where the vast majority of drug

injections still take place.”

“It has been estimated that injection drug users inject an average six injections a day of cocaine and four injections a day of heroin. The street costs of this use are estimated at around $100 a day or $35,000 a year. Few injection drug users have sufficient income to pay for the habit out through employment. Some, mainly females get this money through prostitution and others through theft, break-ins and auto theft. If the

theft is of property rather than cash, it is estimated that they must steal close to $350,000 in property a year to get $35,000 cash. Still others get the money they need by selling drugs.”