Donavan Sutherland faced a tough reality nearly three months ago.

The 18-year-old was looking at charges of aggravated assault and domestic assault stemming from an incident this past summer with his partner Lisa Chubb.

“My worst case scenario I was thinking in my head I’m going to get like a month in Dauphin jail,” Sutherland told APTN News.

That changed when he decided to get help navigating the criminal justice system.

Sutherland is one of the 4,500 people who went through a restorative justice program in Manitoba this year.

“It opened my mind to different things and different perspectives,” says Sutherland.

“After going through those things and getting my charges dropped… it did kind of rearrange my thinking.”

According to Canada’s Department of Justice, the restorative justice program focuses on addressing the harm caused by crime while holding the offender responsible for their actions by providing an opportunity for the parties directly affected by the crime – victims, offenders and communities – to identify and address their needs in the aftermath of a crime.

It has been part of Canada’s criminal justice system for more than 40 years but many aren’t familiar with the approach.

The Department of Justice released a national survey earlier this year and found 52 per cent of Canadians know little about restorative justice.

The Southern Chiefs’ Organization (SCO), a group that represents 34 First Nations in Treaty 1 (Manitoba) is working to change this.

The organization has five community justice workers who cover 13 of its communities.

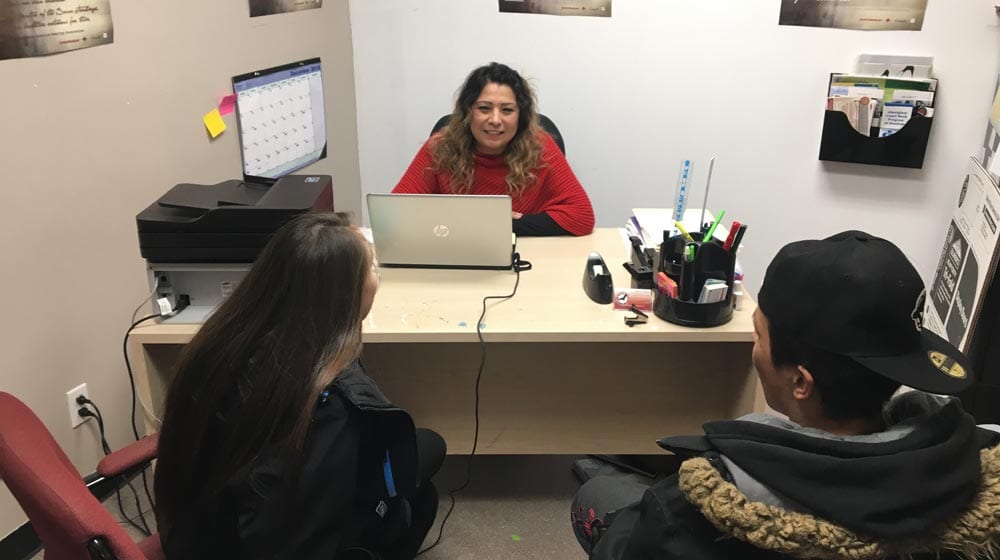

Crystal Nepinak is a criminal justice worker in charge of Pine Creek, Skownan and O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi First Nations.

She is working with Sutherland and Chubb.

(Crystal Nepinak, in red, speaks with Lisa Chubb and Donavan Sutherland. Photo: Brittany Hobson/APTN)

According to Nepinak, in August, Sutherland and Chubb got into an argument while under the influence. Sutherland was charged and sent to a holding cell for the evening.

But Chubb, 19, said she initially started the fight and Sutherland was defending himself.

She was eventually taken to the nearby Dauphin Correctional Centre where she stayed for a week.

After Sutherland was released he went to Nepinak for help before his first court date.

Nepinak developed a plan for Sutherland with the community’s justice committee.

It included traditional healing and workshops.

“Me going to sweats and traditional things it’s really helped with bettering myself, bettering her, my family, friends, people around me in my community,” says Sutherland.

“Basically talking to Crystal and going through all this stuff is making me want to do better for myself, for her [and for] our baby on the way.”

Sutherland and Chubb are expecting a baby next year.

Chubb is in the process of completing her program. She said the experience has made her realize she was being ‘immature’ at the time of the incident.

Manitoba ranks second for the highest number of Indigenous adult inmates in the country, according to Statistics Canada.

Indigenous people make up 74 per cent of the population of inmates but only account for 15 per cent of the overall population in the province.

Nepinak sees her role as much more than one in the community.

“I like to think of our position as community justice workers as not only working with the community but also being eyes and ears in the court system,” she says.

“We’re sitting in a court room, we’re listening, we’re witnessing what’s happening and we’re witnessing how our people are being treated.”

The provincial government has committed to lowering incarceration rates. Earlier this year it released a strategy to divert more people away from jail.

According to the office of Cliff Cullen, the minister of Justice and Attorney General, as of Nov. 30 – 4,503 cases have been diverted. In 2017 the number was 4,426 for the entire year.

“A lot of our people going right to court – there’s nothing learned at all but when they come through our program they start to understand more of the process and how they got there, why they’re there and what it takes to get out of there,” said Nepinak.

The SCO is working at adding more programs including one in Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation.

Nepinak says this is necessary.

For the past year-and-a-half she has worked at educating local RCMP and police officers on the option of restorative justice.

She says support from the courts and law enforcement hasn’t always been there, but it’s slowly changing.

Nepinak, who also went through a diversion as a youth, feels the program is successful.

She’s witnessing it with Sutherland and Chubb.

“They’re so involved now in the community and they’re so active. They’re a new couple, they’re going to have a baby and they’re so actively trying now to attend any program that they could that will help them be stronger as a family,” she said.

While awareness of Restorative Justice is growing, and more and more cases are being diverted, there remains a significant lack of common understanding of the distinction between the restorative model and the “colonial” model of justice.

Restorative is the key word, in that the RJ process is designed to foster a sense of responsibility and agency which may have been lost. The harms are a key component – they must be addressed – but so too are the needs of the participants and the surrounding community. There is great value in bringing people out of isolation and into safe and open communication.

In terms of practitioners, the skills and abilities required are unique, and do not directly mirror those associated with justice or mediation. The RJ process is often emotional, and practitioners must possess the ability to engage with the parties on this level. In many cases, there is no set script or rote methodology, but rather a carefully constructed PROCESS, which allows space for personal experiences while upholding the safety and dignity of everyone involved.

The community dialog model takes its inspiration from the practices of many of our First Nations, in that it relies upon the wisdom of community and shared experience to generate individual accountability.

I urge people to read more about Restorative Justice and to consider participating. There are roles such as “community member”, which require only an understanding of the impacts of crime on the community and a true desire to help people.

While awareness of Restorative Justice is growing, and more and more cases are being diverted, there remains a significant lack of common understanding of the distinction between the restorative model and the “colonial” model of justice.

Restorative is the key word, in that the RJ process is designed to foster a sense of responsibility and agency which may have been lost. The harms are a key component – they must be addressed – but so too are the needs of the participants and the surrounding community. There is great value in bringing people out of isolation and into safe and open communication.

In terms of practitioners, the skills and abilities required are unique, and do not directly mirror those associated with justice or mediation. The RJ process is often emotional, and practitioners must possess the ability to engage with the parties on this level. In many cases, there is no set script or rote methodology, but rather a carefully constructed PROCESS, which allows space for personal experiences while upholding the safety and dignity of everyone involved.

The community dialog model takes its inspiration from the practices of many of our First Nations, in that it relies upon the wisdom of community and shared experience to generate individual accountability.

I urge people to read more about Restorative Justice and to consider participating. There are roles such as “community member”, which require only an understanding of the impacts of crime on the community and a true desire to help people.

The leadership and the rest of the administration have to learn restorative justice as well. Some of our first Nation communities make it contradicting when asking for criminal record checks if one is to seek employment. Some communities dwell on someone’s past and these employment seekers get screened out automatically due to a criminal record. We practise the 7 sacred teachings and there is no forgiveness in the teachings. So they have to forgive what has been done in the past and let people move on for the better. Otherwise, there is no hope for that person or persons.

The leadership and the rest of the administration have to learn restorative justice as well. Some of our first Nation communities make it contradicting when asking for criminal record checks if one is to seek employment. Some communities dwell on someone’s past and these employment seekers get screened out automatically due to a criminal record. We practise the 7 sacred teachings and there is no forgiveness in the teachings. So they have to forgive what has been done in the past and let people move on for the better. Otherwise, there is no hope for that person or persons.

A profound process for both perpetrator and victim. My family participated in a restorative sentencing circle after the loss of a family member due to someone’s unintentional actions. This process saved many lives and answered many questions and allowed us all to continue living in the same community. I am so grateful we had the chance to heal in this way.

A profound process for both perpetrator and victim. My family participated in a restorative sentencing circle after the loss of a family member due to someone’s unintentional actions. This process saved many lives and answered many questions and allowed us all to continue living in the same community. I am so grateful we had the chance to heal in this way.