Edith Wells, the mother of Jon Wells, carries flowers to the Carriage House hotel in Calgary where he died. Photo: Ramsey Kunkel Photography.

The family of Jon Wells says his death during a violent interaction with Calgary police officers on Sept. 17 has left a gaping hole in their lives and a massive void in the community.

The 42-year-old Blackfoot cowboy was a beloved son, brother, nephew and cousin, his grieving relatives told APTN News in an emotional interview.

He was also the father of three girls.

Melissa Crying Head is one of Wells’ sisters.

“It’s the trauma that I have to live with every day,” she says, her voice shaking.

“The trauma that I look at and I could feel my brother, I could feel the fear that he had in him, I could feel him so close to me that he was scared.”

The Fox-Wells family is a prominent member of Kainai First Nation, also known as the Blood Tribe. The reserve about two hours south of Calgary is the biggest in Canada by area.

The family is angry about how Wells was treated while seeking a room at the Carriage House Inn just before 1 a.m. after a weekend outing ended in a disagreement with his common-law wife. He was normally peaceful, friendly and kind, they say.

“I was upset when I heard some of the news reports when the manager referred to Jon as an unwanted transient coming into his hotel,” says his aunt Adelaide Creighton.

“My nephew was not a transient. He had class. He worked. He was not a bum.”

But he may have been drinking, the family says, and stuttered when he was upset.

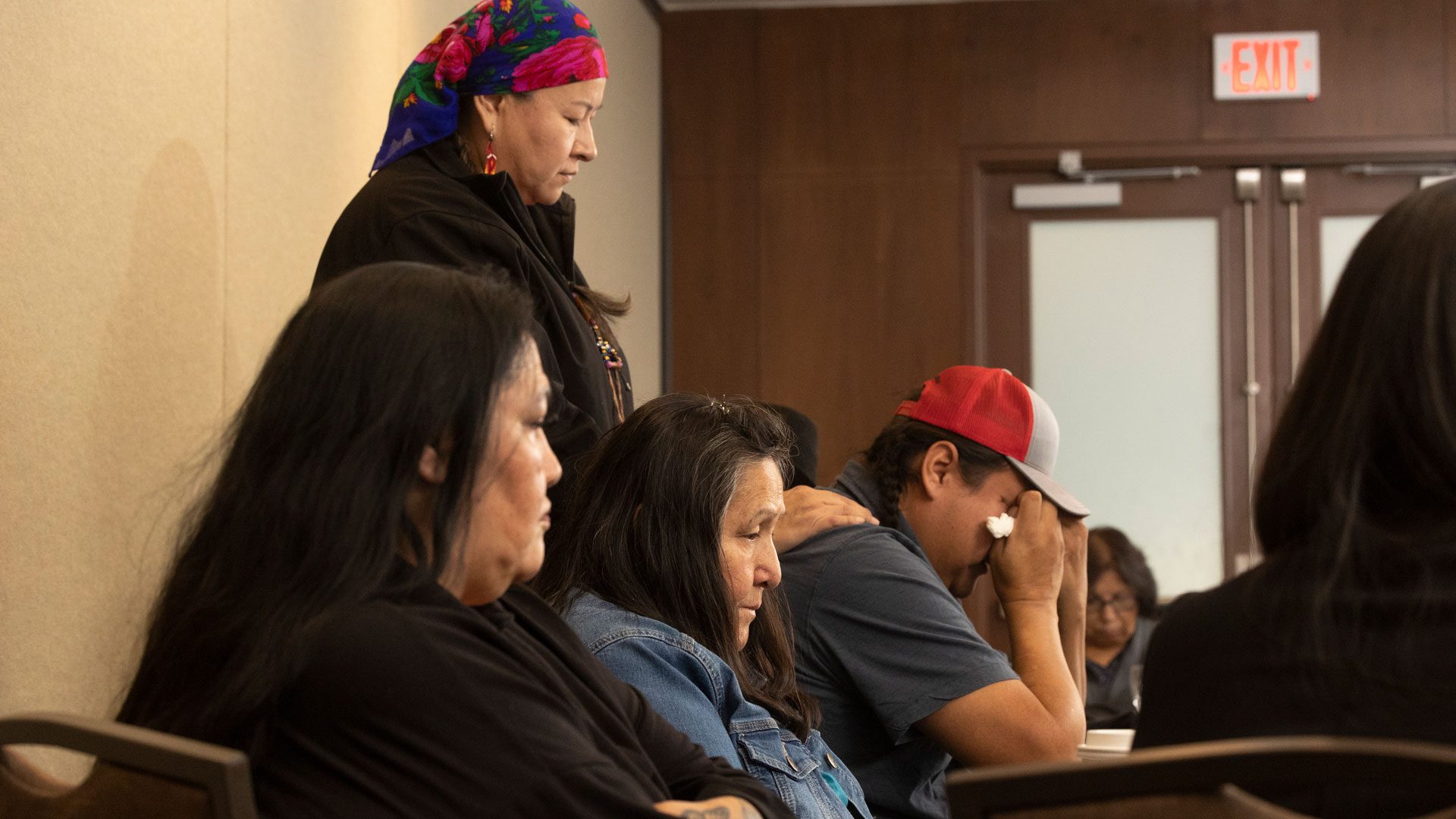

The details of what happened after the hotel called the Calgary Police Service (CPS) non-emergency line are hard on family members. They close their eyes and shake their heads as relatives question certain points.

Wells’ mother Edith Wells clutches an eagle feather gifted to her by the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Cindy Woodhouse-Nepinak.

‘The interaction’

The Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT) says in a Sept. 25 news release that Jon was subjected to “various uses of force” by three officers. ASIRT investigates the police when members of the public are harmed during an interaction.

Details of the in-custody fatality vary depending on the source of the information. According to CPS, they received a call about a man causing a disturbance at the hotel.

“Officers attempted to de-escalate the situation; however, the man was not cooperative,” the police said in a Sept. 17 release. “A struggle ensued, resulting in one officer deploying a Taser. The man continued to be combative with officers, resulting in one officer deploying OC (pepper) spray. The man was taken into custody and, shortly after, went into medical distress.”

But a week later, in a somewhat unprecedented move, ASIRT presented a very different narrative.

It suggested officers’ actions didn’t “de-escalate” the situation, but rather had the opposite effect. ASIRT released its statement based on video recorded by the officers’ body cameras.

“Tsiksikokiimaa” = losing someone special

According to ASIRT, Jon was near the check-in desk when the first police officer arrived.

“The male is standing with his hands in full view and does not possess any weapons,” ASIRT said in its release. “The male continues to stand at his location in the lobby and act in a confused fashion, such as attempting to pick up items off the floor that were clearly non-existent.”

After speaking with Jon for about 30 seconds, the officer “points his conducted energy weapon (Taser) at the male and orders the male to leave the lobby.”

“The male raises his hands and confirms he’ll leave and asks the officer not to shoot him,” the release said.

“I don’t want to die,” it quoted Wells as saying as he moved towards the front door of the hotel.

“He wasn’t combative,” says Creighton. “He wasn’t making a fuss.”

ASIRT’s release confirms that.

It also says, “At no point during the interaction had the male been identified, nor was he ever told he was being detained or under arrest.”

Jon, who was about 6’2” and 190 pounds, stopped when two more officers confronted him. The first officer on the scene then tried to grab him. He did “physically” resist, the release noted, but did not deserve what happened next, says Crying Head, while fighting back tears.

“These are the people who are supposed to serve and protect people,” she says. “I have to wake up every day knowing that my hero’s gone.”

ASIRT says the officers tackled, punched and Tasered Jon before binding his hands and feet behind his back and covering his head with a spit hood.

He is “noted to be bleeding from the mouth and vomits,” the release said.

A relative who works in healthcare says it was dangerous to put the hood on Jon. The relative, who asked not to be named, questions whether Jon could breathe.

“So for me, I’m still thinking what ended his life? Was it the Taser or was it the sedation?”

Paramedics arrived to find Jon face down on the floor in handcuffs and leg restraints, the release said. The paramedics administer a sedative.

Here, a cousin speaks up.

“They don’t seem to check his vital signs,” says the cousin, who also works in healthcare and asked to remain anonymous.

“I was a paramedic for 18 years and you’re supposed to assess a patient’s colour and breathing. There are protocols to follow.”

The release says several minutes passed before paramedics noticed Jon is unresponsive.

“The male was then provided medical care but declared deceased at the scene,” ASIRT said.

The Alberta College of Paramedics told APTN its members are permitted to administer medication to a person in police custody.

“Paramedics have the authority to make this decision while following specific guidelines and protocols put in place by their employer,” said college registrar Tim Ford in an email.

The province says the family can launch a complaint against the paramedics through the college.

Family members concerned

Jon’s father Larry Fox wants answers from the City of Calgary, CPS and paramedics.

“Jon meant everything to me,” he says, while sitting beside his wife Donna and his four older sisters. “He was kind, a kind man; he helped everybody.

“And right now, all I want is answers, I just want justice.”

Edith, a residential school survivor, can only share a few words before collapsing in tears.

“On September 17 at 9:34 a.m. I received a call. He says, ‘This is (a) detective calling.’ I say, ‘Is my son OK? Can I come and see him? Which hospital is he at?’

“And he said, ‘Your son is not coming home.’”

Later, Edith reveals ASIRT has completed its investigation, but is still awaiting autopsy results. The family has been told to expect a copy of the final report, she adds.

At about noon on the day Jon died, an Indigenous liaison officer with ASIRT met family members at Edith’s home in Lethbridge northeast of Kainaii, says sister Megan Wells.

“He came down and told us how everything had happened,” she says. “He told us to focus on getting Jon home, the funeral arrangements, giving him a proper burial.

“And, after that, we would have to get someone like an Elder representing us with ASIRT.”

ASIRT has not said anything more publicly. It can recommend to the Alberta Crown Prosecution Service that criminal charges be laid against police officers.

Alberta’s Justice Department says it is not clear when the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner will have the autopsy ready.

‘I’m not going to stop until someone is held accountable’

The family is aware that Jon’s death marked the eighth time a First Nations person was killed in Canada during an interaction with police since Aug. 29, a crisis that prompted an emergency debate in the House of Commons on Sept. 16.

The number of Indigenous people (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) to die during the same period while in custody of police is now up to 13.

Kainai Chief Roy Fox called for a public inquiry into Jon’s death at the AFN’s special meeting in Calgary on Oct 16. The resolution passed unanimously.

“My brother was (allegedly) murdered,” says Melissa. “I’m going to stand and be that voice that justice is going to be done.

“I’m not going to stop until somebody is held accountable.”

First Nations like Kainai have been overwhelmed by drug addiction and overdoses, outpacing their communities’ limited health resources.

As a day school survivor, Jon played a special role in helping people overcome their addictions, says his brother-in-law Grant Crying Head.

“My wife and I have been sober 10 years thanks to Jon. He always encouraged us. He said, ‘Brother, you can beat this. You’re strong.’”

Jon’s willingness to help others was never-ending, says his family, who described numerous ways he made a difference in their lives and in their community.

As part of a rodeo family, Jon’s passion was riding horses, wrestling steers and taming wild broncos with a wall of international honours and belt buckles to show for it.

“I missed Jon at the Indian National Finals Rodeo in Las Vegas in October,” says Creighton. “Somehow he always qualified.”

His energy on the job was unmatched and forward-thinking, notes Melissa.

“He was loved by many,” she says. “(His death) didn’t just affect us as a family but it affected us as a Nation.

“People he worked with feel that emptiness,” she adds. “They said the agriplex (where he was Ag Society president) will never be the same because Jon isn’t there.”

His aunts say he kept in touch via text.

“He was always there to help,” says Audrey White Quills. “You never heard him yell at anybody or get mad at anybody. He was always there to help the next person.

“If anybody needed a shirt, he would give his shirt to them. He was just that kind of a guy.”

When she lost her son, Michael White Quills, in April, Audrey says she was buoyed by the special bond her son had with Jon.

“They were rodeo buddies,” she says. “They went on the rodeo trail together. Jon was a big brother to Mike.”

Rosaline Crow Shoe says she’s never saw Jon get mad.

“For this to happen to my nephew, my baby brother’s son – really, really, really hurt me,” she says.

“I want to see justice done. I want to see what exactly happened to him. Why did this happen to him? He didn’t deserve it.”

“Kiimaapiipitsin” = kindness, humility

With his hand on his wife’s shoulder to comfort her, Grant says he feels Jon was racially profiled at the busy hotel where First Nations do a lot of business.

“Why wouldn’t he think they’d give him a room? He worked for the Blood Tribe.”

The deadly interaction has devastated this close family. Their anguish evident during a two-hour meeting with APTN at a hotel near the Carriage House.

“When I heard on the news that a man had died at the hotel I thought, ‘Oh no, is it one of our band members?’” says Leslie Wells, a sister.

“I was shocked to learn it was Jon.”

Older brother Craig Wells is struggling to understand how police acted. And why they used both pepper spray and Tasers.

“It still hurts thinking about (it),” he says, taking deep breaths to steady himself. “Today, I’m trying to find stuff to keep me busy, keep me going. If I sit idle I’m going to get angry.”

Looking back, Craig says Jon had his troubles but kept moving forward.

“He pushed himself for the community, he started doing stuff for the community. It made me proud what he was doing,” he says.

In August, he says Jon joined the Horn Society (an important step in Blackfoot spirituality) and “became his big brother.”

But never forgot the next generation.

Jon started a basketball program for young people, Craig says, and helped with a riding program for youth. And then he developed his own program using horses as therapy for youth and men in active addiction, says Leslie, the community’s opioid response coordinator.

He was also involved in the return of buffalo to the Blood Tribe that derived its name from bison hunting.

“He researched and he studied them,” says Melissa. “Even when they unloaded (the animals) he gave special instructions so they would not get sick.”

Jon had a winning smile, big hugs and a happy outlook, says Megan. His youngest daughter, who is now two, bears a striking resemblance to her father.

“He’d call and tell me to get out of bed,” recalls Megan, noting Jon was helping her raise her two daughters.

The family held a ceremony at the hotel the day after the tragedy followed by a march to the nearby Calgary police detachment. The manager of the hotel was there but never aproached the family, says Melissa.

“There is a name in Blackfoot for this grieving,” she says. “Ao’ohkssa’taki.”

Her mother has forgiven the people involved and asked her to do the same.

But, she says, “I’m not ready. I’m not going to let this go.

“He had so much to do, so much more to do. It wasn’t his time.”

Edith has been leaving fresh flowers at the spot where Jon died whenever she is in Calgary.

“I told them I am putting them here for my son,” she says of hotel staff. “They didn’t say anything.”

According to the Alberta government, the death of Jon Wells could be the subject of a provincial inquiry.

With files from Mark Blackburn