Blood Tribe/Kainai Nation harm reduction house in Stand Off., one of the townsites on Kainai Photo: Danielle Paradis

In the morning at the Blood Tribe Harm Reduction Project, Twila Singer a peer support worker, opens the house and starts the coffee. The weather is bad so no one is expecting a busy day.

Singer took some time off work to raise her kids and she is getting back to work through her time at the project. She told APTN News that as a part of her work, she meets people where they are at in a non-judgemental way.

The project provides materials to help reduce that damaging effects of opioids. Everything from safe supply to medication that helps during an overdose.

Singer believes it is important to fight a lot of the shame that comes with addiction.

“It is not just within a family. Within a community. Within a town. The shame comes from colonization from residential school,” said Singer.

On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays the group offers a meal. People living with addiction sometimes forget or are unable to feed themselves.

Today, chili is on the menu.

A couple comes in to grab food and talk. They had been looking for housing options and have heard that they will get Treaty 7 housing in Lethbridge, which is 62 km from Stand Off, the townsite where the harm reduction house is located on the Kainai/Blood Tribe Nation.

They leave with large smiles, warm food and a few words of encouragement.

The staff at the house tell APTN that they have seen changes in the time that they have worked there.

“The thing about tough love is that it doesn’t work. It is not our way,” said Singer.

She learned about the need for tough love in some of her classes on addiction but she doesn’t believe it is the right way to deal with people in addictions.

“We have seen miracles happen just by being there … we are the one place where they can come and feel like they aren’t going to get that shame and judgement,” said Singer.

Singer also feels that keeping in contact with people who are in addictions, rather than shunning them leads to them going to treatment.

“When you ask a lot of people in recovery how they keep going they say that so-and-so didn’t give up on me or so-and-so kept checking on me. It’s usually their mother,” she said.

That is why she believes there always needs to be a safe supply option, for times when people can’t fight the pull of the drugs.

This is part two in a series. Read part one here: Kaina Nation, opioids and the children left behind

Rylan Red Crow, another worker at the harm reduction house has his own experiences with addictions, namely alcohol.

As a young person he was on the rodeo circuit riding bulls.

“I was a good kid until I was 18. I was focused on rodeo basically. I rode bulls and even went down to Vegas,” he said.

He wasn’t aware of any addiction in his family, or the way that he was susceptible due to that family history.

“Addiction almost took my life five years ago. I was on life support and my lungs everything had just given up … then I just boom woke up,” said Red Crow. “I didn’t go to treatment or any kind of meetings. I was just kind of left on my own because I didn’t know about services.

“I found the house and I started working on projects, like these benches here.”

Red Crow also lost a lot of family members and thinks that harm reduction measures and education are an important part of stopping addictions.

“I’ve lost my mom. I’ve lost my step dad and two brothers all in the span of two years while I have been sober,” said Red Crow.

His stepdad and brother both died to opioid poisonings.

“My mom passed away from cancer and she had her problems but it was prescription pills, not [street] opioids which is another thing that is very rapid around here,” said Red Crow.

From the house, Red Crow said he started to learn healthy coping mechanisms, and about harm reduction.

“I learned about spirituality. The importance of food, food security water. That people need a safe place to go because even family is stressful sometimes.”

Recovery only versus harm reduction

According to statistics from the province of Alberta, the number of people who are a part of the Opioid Dependency Program in the province has increased from 3,049 in 2018 to 7,500 in 2023.

In the southern region of Alberta, where the Kainai First Nation is located, emergency hospitalization rates related to substance use were over 300 people per 100,000 for 2023.

There were 115 opioid poisoning deaths in Alberta in 2023.

The Alberta government has prioritized the “recovery model” as a way to deal with the opioid epidemic in the province.

The philosophy guiding the province on how to deal with addiction was well summarized in an editorial in the Edmonton Journal by then associate minister for Addictions and Mental Health Jason Luan, who wrote that “addiction does not exist in drugs; it exists in people. Therefore, the solution exists in people and not in tinkering with the drug supply.”

The focus on treatment over harm reduction has been a major focus of the government. But some in Kainai believe that both are needed.

“You always see a change depending on the government in power but harm reduction to me is providing help for an emergency, temporary situation. Harm reduction will always be a part of prolonging lives and stop spread of disease, but we are not planning to always be in this situation,” said Singer.

Singer said she does her best to get harm reduction materials in the hands of people in the community.

“We used to ask do you want Narcan, do you want Naloxone? But now I just make them take it … some people don’t want to carry the boxes,” said Singer.

Niki Creighton is another worker at the house.

“I felt everything so much that is why I used,” she tells APTN. Her husband passed away in 2021 due to an overdose and Creighton feels that he left her his strength to carry on.

“Honestly I was treated really bad after his death, but it wasn’t my fault,” said Creighton, her eyes filling with tears at a still painful memory.

Creighton said she removed herself from things that triggered a desire to use drugs.

She said that now, she relies on Creator’s strength to keep going.

“He is the first person I talk to. First thing in the morning and all day. I am pretty much in constant prayer,” said Creighton.

She also finds solace in helping others to find a sober path.

Reducing the effect of opioids

Both Narcan and Naloxone are medications that can be used to reverse or reduce the effects of opioids.

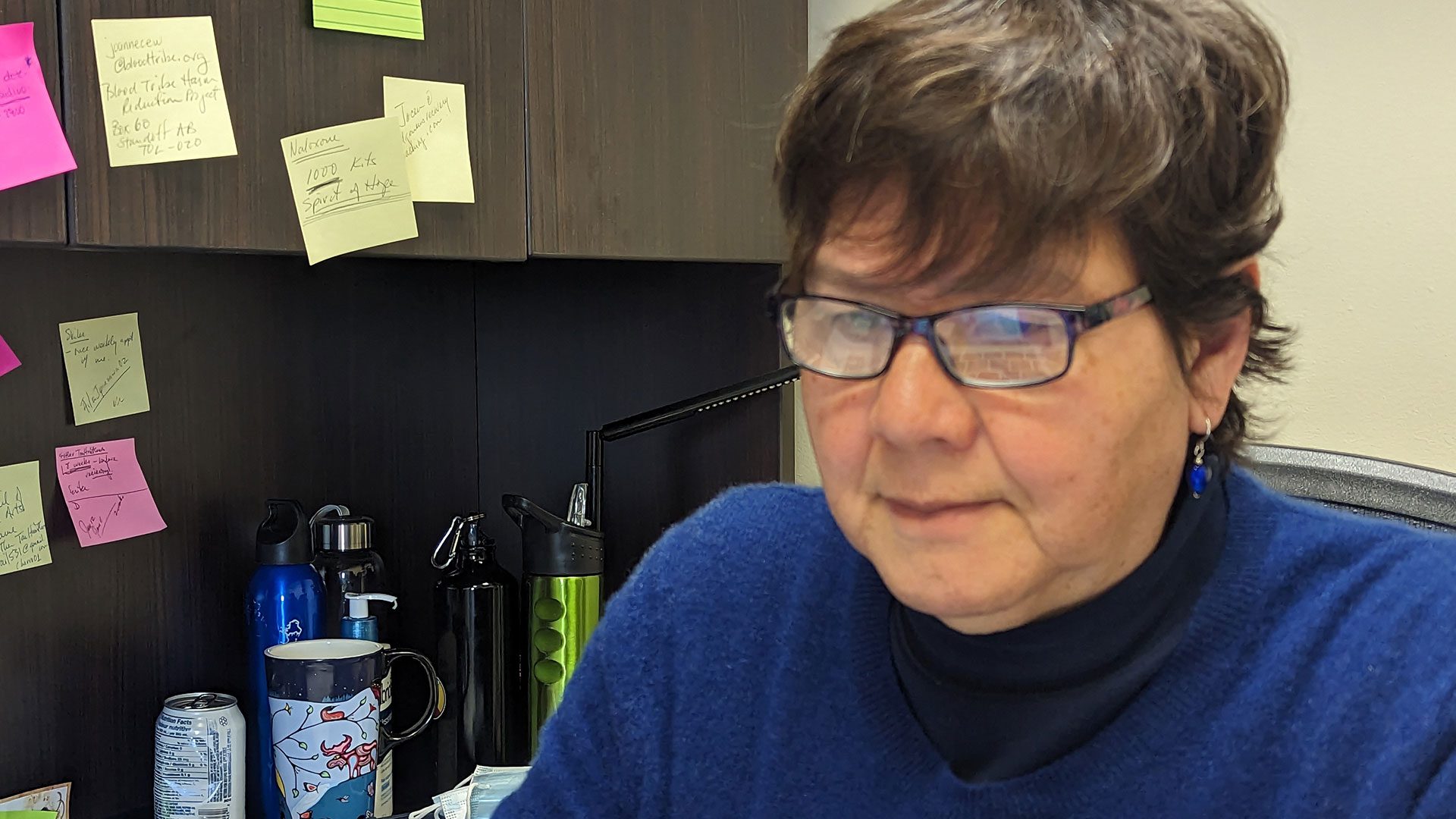

The program is run by Gayle Chase and funded by the Blood Tribe/Kainai First Nation. Chase tells APTN News that she is always looking for ways to keep the lights on for the project and to promote positive stories to the community.

“There’s been so much devastation but there’s also a lot of progress made,” said Chase. “People are working to push past the hurt and death.”

Chase was hired to start the harm reduction program in 2015, when drugs in the community were Oxy-80s, strong opioids originally intended for cancer patients.

“We weren’t even able to distribute Naloxone at the beginning because it was only for health care professionals,” said Chase.

The community is a dry reserve but works to support initiatives for safe supply. They do not currently offer that service at the harm reduction house.

Read More:

First Nations life expectancy plummets in Alberta due to opioid deaths

Kainai/Blood First Nation is fortunate to have another ally in the fight against opioids. Their very own homegrown doctor, Esther Tailfeathers.

Tailfeathers both lives and works in Kainai First Nation. Her home is in the community of Moses Lake, which is a part of the Kainai/Blood Tribe but she works in Stand Off a clinic.

She spoke to APTN at her log house about the beginning of the drug poisonings and the need for more care facilities and treatment options.

“Before we really got into the naloxone and Narcan, there were two deaths in the community on March 30, 2015. two deaths were parents that overdosed at the kitchen table and when their kids got up in the morning they found them deceased there,” said Tailfeathers.

Tailfeathers has been outspoken in support of harm reduction measures needed in the province.

“We were really the first to start talking about harm reduction and proving that harm reduction works by teaching people to use naloxone. The proof is in saving lives,” she said.

People were afraid to use Narcan and naloxone in the beginning but Tailfeathers said that once stories started to spread about saving lives, that convinced other people in the community that these medications would help during the opioid epidemic.

She has also been working to help people in her community and across the province understand the scope of the problem.

“Some think that these people who are addicted and on the streets have the option of going to treatment? They don’t even have the option of going to detox,” said Tailfeathers. “These treatment centres are bogus because they are not even open so where is this place that they are supposed to go?”

In January 2019 there was a ribbon cutting for a 12 bed, 24 hour treatment facility in Kainai and in 2020 former premier Jason Kenney announced $5 million in funding for a new centre, but it’s not yet complete.

Tailfeathers would like to see the ability to test the drugs people are using available as another harm reduction measure.

“If people were testing their drugs in private they could plan to have someone with them or alert the community about what is in the latest batch,” she said.

In her nine years of working through the opioid crisis, Tailfeathers said she has continued to learn more about the difficulties of addiction.

“I had a very linear thinking about ok they start here in bad shape. We put them in detox, they go to treatment, we support them and they get better,” she said “It’s now almost ten years later and there’s still many many people who went through those things but they still died.”

Tailfeathers said it has been a difficult past few years and people whose success she had celebrated had also fallen back into addiction.

“These addictions are much stronger than we understood…there’s always something that might push someone into relapsing,” said Tailfeathers.