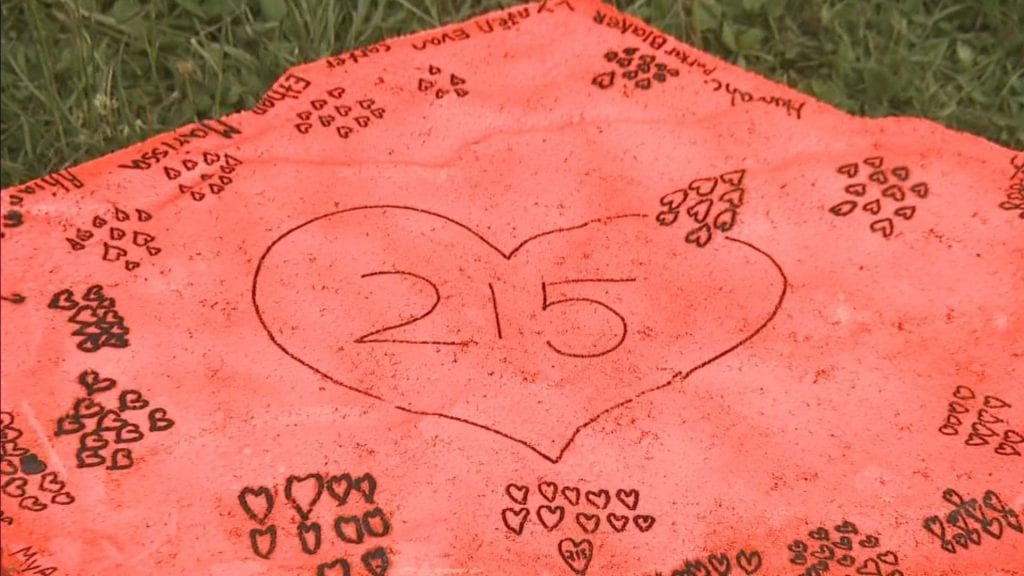

The AFN election happens not long after the discoveries of nearly 1,000 unmarked graves at former residential schools. Photo: APTN

The question of how to get justice for victims of residential schools arose several times during the Assembly of First Nations all-candidates forum Tuesday night as day one of its 42nd annual general assembly concluded.

Seven contenders with more than a century of political experience between them seized their last chance to impress 357 chiefs and proxies registered to elect a new national chief.

“Chiefs, I want to acknowledge that you have the hardest job in this country,” said Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse, executive director of the Yellowhead Indigenous Education Foundation and former band councillor from Alberta.

“You are leading a group of peoples coming out of genocide who are continually re-victimized and re-traumatized.”

Calahoo-Stonehouse pledged to support the fight for justice and accountability. She said the AFN needs to get back to its original mandate and stressed importance of data sovereignty and need for a comprehensive digital strategy.

Reginald Bellerose followed by showing off a belt representing Treaty 4 with the Crown.

“In this belt, you do not see the Indian Act, you do not see residential school, you do not see the foot on the throat of our people for 100-and-some years,” said Bellerose, long-time chief of Muskowekwan First Nation in Saskatchewan.

Bellerose urged the chiefs to consider his 17 years of local experience when they cast their vote tomorrow morning.

“If the Crown wants to see transformational change in the relationship with the Indigenous peoples, the following must be done: trust, restitution, restoration — then reconciliation,” he said.

Cathy Martin acknowledged the crises gripping communities across the country, whether it be discoveries of unmarked graves, the pandemic or wildfires.

Martin said addressing systemic racism, influencing legislation and potentially revisiting the AFN charter to build bridges with traditional governments were her priorities.

“Systemic racism is the underlying cause of the majority of common issues we face as First Nation people in Canada,” said Martin, an elected councillor for the Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government in Quebec.

“It includes everything from underfunded service programs to blatantly racially motivated actions against our people.”

Kevin Hart said he would fight to break down barriers to ensure chiefs are heard on issues ranging from child welfare, homelessness, the opioid crisis and the pandemic.

“Our rights are being violated each and every day,” said Hart, a former Manitoba regional chief and Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation member. “Governments do not have the best interests of First Nations at the table.”

Hart promised to deliver an action plan within 100 days if elected and pointed to his track record as portfolio holder of high-profile issues such as litigation at the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

“I want to continue to fight for our children,” he said. “I want to continue to fight for those children found in those unmarked graves, I want to continue to fight and find justice for our survivors that are out there right now.”

Lee Crowchild told a story to begin his presentation while saying his priorities were asserting jurisdiction, culture, strategic thinking and leadership.

“There is a need for big reset,” said Crowchild, former xakiji, or chief, of Tsuut’ina First Nation and second candidate from Alberta.

Crowchild aimed his candidacy at bringing “transparency” and “integrity” to the office of the national chief.

“The AFN has become irrelevant,” he said. “It has to become relevant to the voices of the chiefs across Canada. And I’ve said that all along.”

RoseAnne Archibald urged the delegates to make her both first woman national chief and first national chief from Ontario.

“Send a clear message to the women that you love,” said Archibald. “Show them that they matter, show them that they can see themselves at the AFN.”

Archibald, former Ontario regional chief and the first woman elected chief of her home community of Taykwa Tagamou Nation, has been pushing for accountability and transparency at the AFN executive.

It was one reason why her supporters urged the chiefs to consider her candidacy.

“Now more than every we need a stable and strong leader who is committed to evolutionary change,” said Archibald. “I am that person.”

But Ontario has one more candidate, which could split the chiefs in that province.

Alvin Fiddler presented last, but he too said his first priority is justice for First Nations kids.

“We are still reeling from the recent revelations of those little ones who never made it home from Indian residential schools across the country,” said Fiddler, a Muskrat Dam First Nation member who served as Nishnawbe Aski Nation grand chief since 2015.

“I am committed to supported the sacred work that needs to happen of finding, identifying and bringing them home,” he said.

Read More:

Vote for AFN national chief will go ahead as planned Wednesday

Prior to the discussion, the delegates gave the new national chief, whoever it is, a mandate to do this work.

Two draft emergency resolutions hit the floor directing AFN to seek justice for the victims of residential schools and hold the perpetrators — Canada and the Vatican — accountable at the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity.

The government estimates 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis kids were forced to attend the church- and state-run institutions designed to weaken family ties, destroy cultural links and eradicate Indigenous cultures through indoctrination.

The TRC travelled across the country finding facts and gathering survivor testimony for years and, in its 2015 final report, documented the suffering, neglect, abuse, disease and death that ran rampant in the institutions.

The commission estimated between 4,000 and 6,000 kids died, but the report said the true number of deaths may never be known because of missing or destroyed records.

Many Canadians, including federal politicians, have begun referring to the institutions as genocidal following discoveries of unmarked graves at former residential school sites in British Columbia and Saskatchewan.

The chiefs struck a similar tone on Tuesday afternoon, saying burial sites containing unmarked graves need to be treated as crime scenes. The resolutions passed with 90 per cent and 100 per cent support respectively.

Chiefs worried earlier in the day about low turnout, as normally upwards of 500 chiefs and proxies attend. Registration remains open.

The first ballot begins Wednesday morning and the winner must secure 60 per cent of however many votes are cast.

The Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program has a hotline to help residential school survivors and their relatives suffering with trauma invoked by the recall of past abuse. The number is 1-866-925-4419.