Carol Dubé tries to make it to his late wife’s graveside every day to give her a report.

Some days he’s held up mopping the floors, or getting his kids off to school – typical things that would tie up any father of seven left to tend house on his own.

But it’s a ritual he’s practiced consistently since late 2020, when Joyce Echaquan was put to rest in her home community of Manawan, just over 250 km northwest of Montreal.

It’s mid-November and Manawan is already blanketed in snow. Carol Dubé arrives at the cemetery in a t-shirt and a light flannel jacket, but the cold doesn’t seem to bother him.

He wipes a layer of freshly-fallen snow from the simple wooden cross that sits atop Joyce’s plot. He kisses the cold wood.

There’s an image of Joyce’s face painstakingly etched into the wood grain. In it, she is smiling.

“I came to see you, came to embrace you,” Dubé says, his voice barely above a whisper. “I adore you.”

It’s a conversation much more tender than the last one Joyce was subjected to.

It’s been over a year now since 37-year-old Joyce Echaquan live-streamed her last, agonizing moments of treatment at Joliette hospital, 180 km south of Manawan.

Her dying cries – and the racist taunts she was subjected to – ignited a movement calling for health care reform across North America.

Despite the public indignance, the Echaquan- Dubé family has had little closure.

The nurse seen on video hurling insults at Joyce received a one-year license suspension from the Quebec Order of Nurses.

Joyce’s Principle, the health care reform proposal tabled by the Atikamekw Nation in Joyce’s honour, has twice been rejected by Quebec’s National Assembly over its call for the provincial government to acknowledge their issues with “systemic racism.”

Today, according to Dubé, donations to the Justice for Joyce cause are dwindling. He feels society is gradually losing interest.

After months of courting, Dubé and his family opened their heart and home and allowed APTN News to pay them a visit in Manawan.

Even though the world may be moving on, Dubé and his children remain immobilized by their loss.

“It was so much easier with Joyce – so much simpler. The other day, I wanted to buy gifts at Walmart, but I kept going in circles. Today, everything is harder for me,” Dubé told APTN’s Nouvelles Nationales in French.

“I say all the time ‘I’m doing well,’ but I’m not. I’m not doing well.”

‘I threw the phone on the floor’: The impact of Joyce’s last video

Without question, Joyce Echaquan was Carol Dubé’s soulmate.

The pair met as teenagers and shared a mutual love of nature, hunting, and their Atikamekw traditions.

They never technically married, but together, they raised seven children. Their youngest, Carol Jr., was only a few months old when his mother died on Sept. 28, 2020.

Had she survived her stay at Joliette, Joyce would have been surprised with a proposal at Christmas, according to Dubé.

“She was like my boss. She was the one who took care of the house, of the kids. She did all the housework,” he recounted.

“Now it’s my turn, and it’s overwhelming. I thought she took her sweet time with things. But today, I understand how had she worked.”

Joyce had a number of overlapping health issues and was no stranger to Joliette hospital.

In late September, she was admitted to Joliette with severe stomach pains. During their last conversation, Dubé says Joyce was waiting for an endoscopy to determine the cause.

“She called me to say they needed to run some more tests. I was anxious to find out what was causing her pain,” Dubé explained. “She told me to wait, get the kids ready, and make sure I did the housework. Brush [our daughter] Jessica’s hair. That was our last discussion. Had I known, I would have kept her on the phone longer.”

“She told me she was tired and needed to sleep a while. And then we said goodbye.”

On the evening of Sept. 28, while restrained and sedated, Joyce Echaquan opened Facebook and hit the ‘live’ button.

In her last, nine-minute live-streamed video, Joyce calls out in Atikamekw to say she’s in pain, while a team of responding health care workers call her “f*cking stupid,” and “only good for sex.”

Carol Dubé didn’t have a cell phone, or quick access to Facebook, at the time.

“A neighbor came by and told me there was a video of my wife circulating on Facebook. He told me I needed to see it, and that it was important […] my son was coming down the road, arriving in a panic. I could see the fear in his eyes. He told me to go inside,” Dubé said.

“So we went inside. He looked me in the eyes for a long time… like he was hesitating to show me the videos. He started to cry. It was then he showed me the video that his sister filmed.”

Joyce’s eldest daughter – who accompanied her to Joliette – posted her own Facebook live video not long after the first.

In it, she’s seen stroking her mother’s cheek and heard speaking softly in Atikamekw. Joyce isn’t moving. She has a sickly, almost yellow pallor to her skin.

When Dubé saw his daughter’s post, he knew his wife was gone.

“I threw the phone on the floor. That’s when I called the kids over. I got on my knees. I didn’t know what to tell them. But in that video, I saw that she wasn’t breathing – I know that much,” he added.

“I’ve seen death. I’ve found dead bodies,” said Dubé, who once worked as a volunteer firefighter.

“I know death. So I knew right away… I couldn’t say anything, so I just sat there.”

‘Could have been reversible’: The Quebec Coroner’s findings

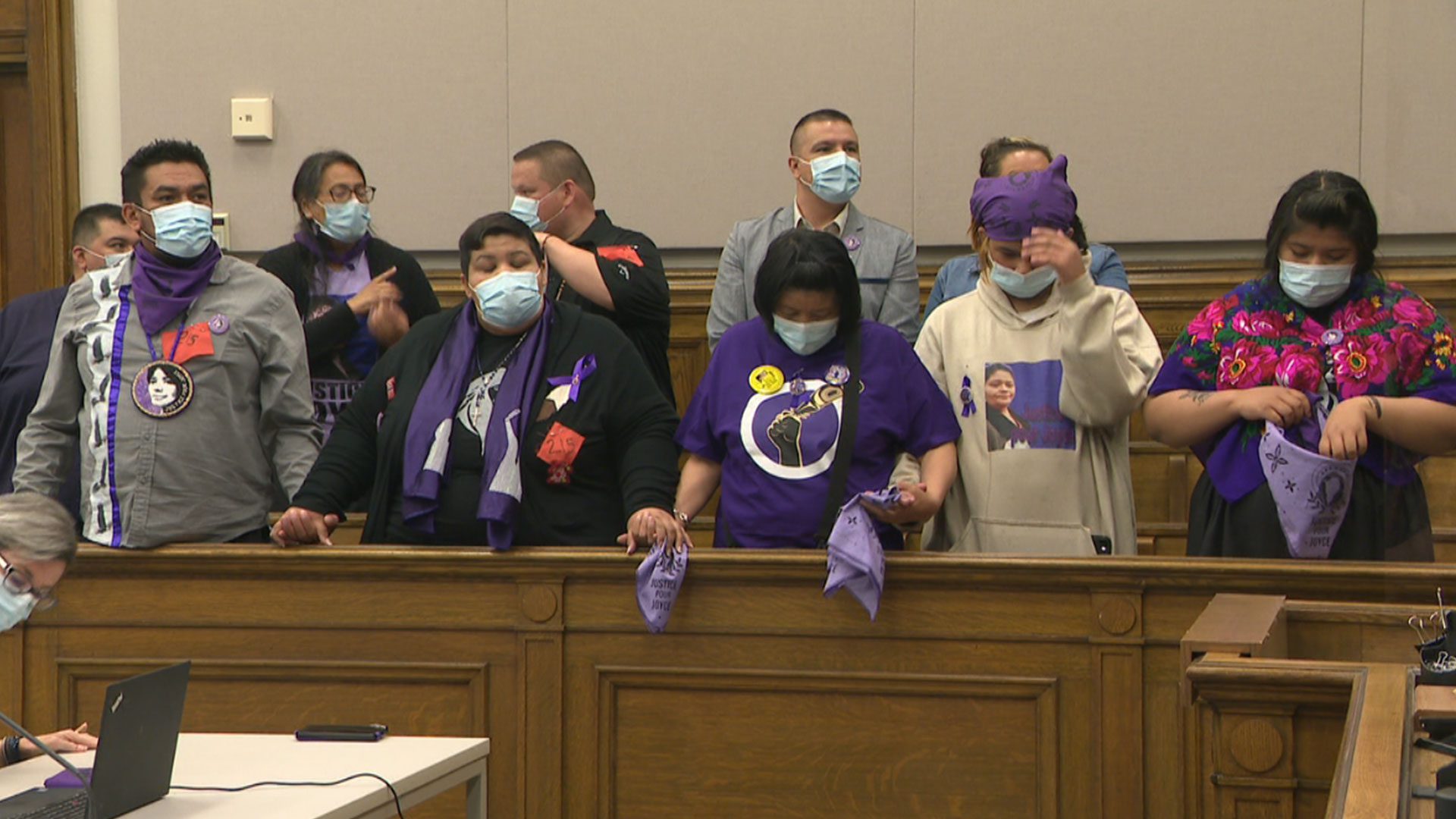

In June 2021, nine months after the world was shocked by Joyce’s last Facebook video, a coroner’s inquest got underway at the Trois-Rivières courthouse.

Over three weeks, lead coroner Géhane Kamel called on the Echaquan-Dube family, Joliette health care workers, experts and scholars to testify.

The final report released publicly in October 2021, determined Joyce’s death was not the result of a criminal act.

Kamel did, however, determine that Joyce’s “clinical situation could have been reversible” if a number of critical care protocols had been followed.

During the inquest, Joliette staffers testified that Joyce was “agitated,” “overdramatic,” narcotic-dependent, and suffering from heart problems brought on by her numerous pregnancies.

The final report states that Joyce died of a lack of oxygen in her bloodstream likely due to chronic heart disease.

However, it also highlighted a number of issues at Joliette hospital: improper use of physical and chemical restraints, inconsistencies in nursing notes, nursing students left with high-risk patients unsupervised, lack of oversight by an Indigenous ‘cultural liaison,’ and a lack of cultural awareness training overall.

In her report, Kamel makes dozens of recommendations calling on the regional health authority overseeing Joliette hospital, the Collège des Medecins du Québec, and the Quebec Order of Nurses to review and amend their current practices in light of Joyce’s death.

But there’s been little movement on call to action number one, for Quebec to “acknowledge and eliminate” systemic racism in its public systems.

Aside from acknowledging Joyce’s death as “unacceptable,” Premier François Legault has long defended his view that “there are racist people in Quebec,” but that the province does not have a “system of racism.”

Joyce’s parents, for their part, told APTN they’re ready to continue pushing.

“I’ll never forget you Joyce – I’ll never forget,” Michel Echaquan expressed tearfully in Atikamekw during a recent interview in Montreal.

“I want to know exactly what happened. I want them to tell us the truth, and to take this to court,” mother Diane Echaquan added.

“That’s all we want to see.”

‘It’s evolution we want, not revolution’

There’s been some movement in the 14 months since Joyce died.

Quebec’s made a handful of multi-million dollar investments to create Indigenous liaison positions at Joliette to disseminate mandatory cultural-sensitivity training for health workers.

A new-and-improved Indigenous-run health centre is expected to be up and running in Joliette by 2025.

Paul-Émile Ottawa, chief of Manawan First Nation, now holds a prominent position within the regional health board overseeing Joliette hospital.

Joyce’s Principle, which was painstakingly crafted after months of consultation with First Nations stakeholders in Quebec, currently has the support of the United Nations.

But the Echaquan- Dubé family say Joyce’s case will have its day in court.

Their lawyer confirmed with APTN that a civil lawsuit is currently in the works, but did not provide details on who will be named in it, or on the dollar amount claimed as damages.

In conversation, Carol Dubé is perpetually calm and soft-spoken. But his gentle demeanor disguises a deep-seated rage, and a grief he’s still coming to terms with.

Not only did he lose his life partner in September 2020 – he lost a part of himself as well: the happy man, grateful to wake up every morning next to the woman he loved.

The man who enjoyed the ritual of hunting, and fishing. The man who volunteered within his community.

The man was able to watch his children grow without feeling the hollow pang of loss.

“It’s all mixed up eh? I didn’t choose to be alone. But when I’m sitting here, I’m flooded with memories. Especially when the kids go off to school, and I’m home alone. That’s when the images come,” Dubé said.

“I think more and more about her.”

Read More:

Birthdays, camping and a newborn child: Joycee Echaquan recorded everything in life

Despite apologies and announcements, little has changed says Joyce Echquan’s community

Joyce’s face is everywhere in the home she once shared with Dubé. It’s visible on prayer candles and posters, drums and dreamcatchers. In paintings and on purple ribbons.

Dubé knows he’ll never forget her.

His life’s work is now making sure society remembers.

“It’s not a revolution we want. It’s evolution,” he says.

With files from Tom Fennario.